Anochetus peracer

| Anochetus peracer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Ponerinae |

| Tribe: | Ponerini |

| Genus: | Anochetus |

| Species: | A. peracer |

| Binomial name | |

| Anochetus peracer Brown, 1978 | |

A nest of this species was found in an epiphitic moss of a downed tree in rainforest. The types were collected (Wilson 1959, note under Anochetus variegatus) during early evening and were found foraging on the lower part of a tree trunk at the edge of rainforest.

Identification

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: -6.733066° to -7.199999809°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Indo-Australian Region: New Guinea (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

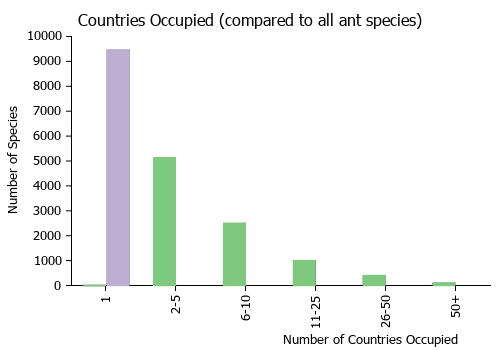

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

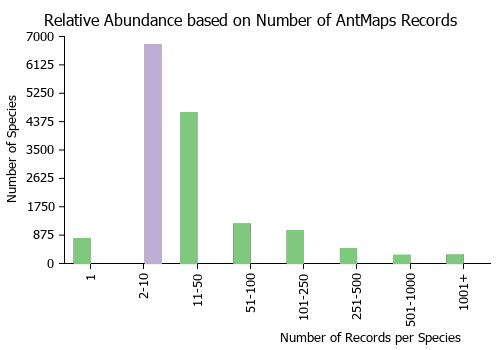

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Castes

Queens and males of this species are unknown.

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- peracer. Anochetus peracer Brown, 1978c: 579, figs. 40, 53 (w.) NEW GUINEA (Papua New Guinea).

- Type-material: holotype worker, 1 paratype worker.

- Type-locality: holotype Papua New Guinea: Lae, Didiman Creek, 29.iii.1955, no. 711 (E.O. Wilson); paratype with same data.

- [Note: Brown, 1978c: 580, says that the paratype has since been lost.]

- Type-depository: MCZC.

- Status as species: Bolton, 1995b: 65.

- Distribution: Papua New Guinea.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

From Brown (1978):

Wilson (1959) assigned this specimen (holotype), along with another worker taken at the same time and place, to Anochetus variegatus, but noted differences in frontal sculpture and petiolar form between the Lae specimens and a paratype of A. variegatus in MCZ. The frontal striation in the A. variegatus types is strong, and extends well beyond the frontal carinae to fan out widely over the center of the vertex.

He says nothing about the differences in mandibular dentition that in my opinion are at least as important. The mesial edges of the mandibles in A. variegatus have the dorsal and ventral margins fused into one coarsely denticulate margin beyond midlength for nearly half the preapical length of the shaft; the most distal (preapical) denticle does not form an acute angle as in A. risii, A. peracer and related species.

A. variegatus, though similar to A. peracer in size and color, seems to me to represent a separate species that links the gladiator and risii groups, but is probably more comfortably placed in the former.

The second specimen of collection No. 711, mentioned by Wilson (1959: 509) and presumably belonging to A. peracer, is not now to be found in the MCZ collection, and I do not know where it is.

Worker

Worker, holotype: TL 5.8, HL 1.43, HW 1.29, ML 0.90, WL 1.83, scape L 1.26, eye L. 0.21 mm; CI 90, MI 63.

Similar to Anochetus risii in form, color and sculpture; yellowish-brown, with corners of head and appendages more yellowish, but the petiole gradually attenuated to a very sharp apical tooth, and the mandibles shorter (and broader in the apical half) and with ventral mesal margin of shafts only vaguely crenulate near the preapical angle, which is acute and directed mesad. Antennal scapes also shorter; surpassing posterior lobes of head by only about the length of the first funicular segment when the head is viewed perfectly full-face. Pronotum smooth and shining, except for the usual transverse-striation of the cervix; frontal striation confined to the area between the frontal carinae. Eyes relatively smaller than in A. risii.

Type Material

Holotype Museum of Comparative Zoology from Didiman Creek, Lae, New Guinea, 29 March 1955, taken in the early evening from lower trunk of a tree in lowland rain forest, E. O. Wilson, No. 711.

References

- Brown, W. L., Jr. 1978c. Contributions toward a reclassification of the Formicidae. Part VI. Ponerinae, tribe Ponerini, subtribe Odontomachiti. Section B. Genus Anochetus and bibliography. Stud. Entomol. 20: 549-638 (page 579, figs. 40, 53 worker described)

- Wilson, E. O. 1959. Studies on the ant fauna of Melanesia V. The tribe Odontomachini. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 120:483-510.

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Brown Jr., W.L. 1978. Contributions toward a reclassification of the Formicidae. Part VI. Ponerinae, Tribe Ponerini, Subtribe Odontomachiti, Section B. Genus Anochetus and Bibliography. Studia Entomologia 20(1-4): 549-XXX

- Brown W.L. Jr. 1978. Contributions toward a reclassification of the Formicidae. Part VI. Ponerinae, tribe Ponerini, subtribe Odontomachiti. Section B. Genus Anochetus and bibliography. Studia Ent. 20(1-4): 549-638.

- CSIRO Collection

- Janda M., G. D. Alpert, M. L. Borowiec, E. P. Economo, P. Klimes, E. Sarnat, and S. O. Shattuck. 2011. Cheklist of ants described and recorded from New Guinea and associated islands. Available on http://www.newguineants.org/. Accessed on 24th Feb. 2011.