Belonopelta deletrix

| Belonopelta deletrix | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Ponerinae |

| Tribe: | Ponerini |

| Alliance: | Pachycondyla genus group |

| Genus: | Belonopelta |

| Species: | B. deletrix |

| Binomial name | |

| Belonopelta deletrix Mann, 1922 | |

A rainforest species.

Identification

Mann (1922) - This species differs from Belonopelta attenuata in its shorter and broader head, the clypeus more projecting and narrowly rounded in front, the more slender and arcuate mandibles with much longer tips, the longer antennal scapes, smaller size and in having on the head coarser, separated punctures in addition to the dense and subtile punctation.

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 24.52827° to 8.948888889°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras (type locality), Mexico.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

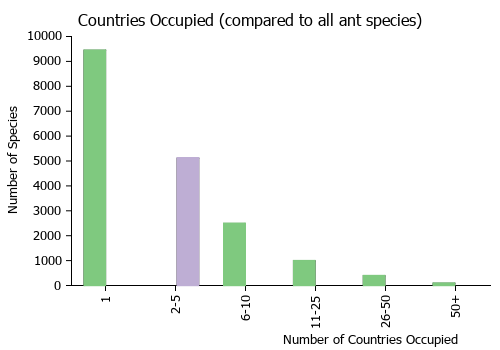

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

Wilson (1955) reported the following in regards to the biology of this species.

In rainforest near the village of Pueblo Nuevo, Veracruz, in the Cosolapa Valley ten miles south of Cosolapa.a single worker was discovered in a rotting, but still firm, section of tree branch, two inches in diameter, buried in deep lea litter between the buttresses of a large tree. It was in a fiat, rectangular, preformed cavity which opened to the soil below by a broad gallery. Six eggs, six larvae, and three worker cocoons were also present, but a conscientious search in the immediate vicinity failed to reveal other adults. Later, a complete colony, undoubtedly independent of the first, was discovered nesting several hundred yards away in a rotting branch, of the same dimensions as the first and also buried in leaf litter between the buttresses of a large tree. This colony consisted of ten workers, a dealate queen, ten eggs, twenty larvae of various sizes, and eight cocoons. It occupied a small cavity the diameter of a pencil and six inches long in the center of the branch.

A third collection of the species was made to the east of Pueblo Nuevo in what might best be described as "tropical evergreen,’’ forest (see Leopold, 1950). The soil was drier and rockier than in the rainforest and the trees formed a single, often-broken canopy with few lianas and epiphytes. The ant auna in general appeared to be little more than a depauperate extension o the rainforest fauna. A colony fragment of Belonopelta deletrix, consisting of three workers, four eggs, and several larvae, occupied a pencil-width cavity in a very rotten, crumbling tree branch three to our inches in diameter lying on the ground and partly covered by rather dry leaf litter. The surface soil and leaf litter in the immediate vicinity were collected in bags, sorted through manually, and then processed in Berlese funnels, bat no more adults or brood could be found.

The rainforest colony and larger colony fragment were maintained in artificial nests during a month’s period for studies on food habits and behavior. In the field, a worker had been found on the undersurface of a limb near the rainforest colony carrying a dead or paralyzed campodeid in its mandibles. In captivity, other campodeids, as well as a single japygid, were quickly captured by the workers and fed to the larvae. Small geophilid centipedes and a single smll cicadellid were also accepted and eaten, but a larger lithobiid centipede was discarded after capture, and other larger centipedes were completely avoided. Termites of the genus Nasutitermes were generally avoided in the first weeks, at the most stung to death and then abandoned, but later, after a month’s confinement and transfer to the United States, the rainforest colony accepted workers of Reticulitermes. Beetle larvae and adults, moth larvae, millipedes, and isopods were avoided. The general impression received is that only a few kinds of small arthropods are readily accepted, and of these, the entotrophan families Campodeidae and Japygidae are the preferred prey. In the Pueblo Nuevo forests, campodeids are abundant (many were on the limb housing the rainforest colony), and they may well form the principal food supply. Honey was ignored by the workers, although available in the artificial nest for at least two weeks.

Despite the rather spectacular development of its mandibles, there does not appear to be anything really unusual about this species’ method of catching prey, although it is admitted that the workers were never seen in the act of hunting uninjured entotrophans, the presumed usual prey. When a brood of newly hatched geophilid centipedes was placed in the food chamber, the ants rushed them immediately, seized them with their mandibles, and shook them back and forth with a forward bobbing motion of the head. Only one individual was stung, in addition, before being carried back to the brood. The Belonopelta, when hunting or fighting intruders, do not open their mandibles more than is usual or other Ponerini. Also, the mandibles are not handled like traps as in other long-jawed groups such as the Odontomachini and Dacetini, nor does their strike have the stunning effect sometimes observed in these groups. My own interpretation is that their peculiar shape is a special adaptation for pinning entotrophans, which insects are very active and agile, and difficult for most ants to hold and sting.

My Belonopelta were generally very timid, in most instances fleeing frantically from arthropods not sought as prey, including the docile Nasutitermes workers. Their mandibles crossed one another at rest as shown in figures 1 and 2 and were never opened to threaten intruders. When the workers transported larvae, they cradled them between the concave masticatory borders and avoided using the needle-like apical teeth. The Belonopelta larvae were very active; when disturbed they thrashed violently back and forth in the manner of injured earthworms, but showed no capacity for directed locomotion. Insect prey were fed to them in typical ponerine fashion on their "laps", either entire or cut up into large pieces. The cicadellid mentioned above was placed entire across the laps of two large larvae lying side by side.

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- deletrix. Belonopelta (Belonopelta) deletrix Mann, 1922: 9, fig. 4 (w.) HONDURAS.

- Wilson, 1955b: 82 (q.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1964b: 452 (l.).

- Combination in Leiopelta: Baroni Urbani, 1975b: 309; Brandão, 1991: 331;

- combination in Belonopelta: Bolton, 1995b: 80.

- Status as species: Wheeler, W.M. 1935d: 11; Wilson, 1955b: 82; Brown, 1950e: 245; Kempf, 1972a: 37; Baroni Urbani, 1975b: 309 (redescription); Brandão, 1991: 349; Bolton, 1995b: 80; Zabala, 2008: 137 (in key); Branstetter & Sáenz, 2012: 262; Fernández & Guerrero, 2019: 517.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Length 4 mm.

Head, excluding mandibles, longer than broad, broadest and with sides more convex in front of middle, posterior border feebly concave. Mandibles, when closed, crossing at middle, long, slender, and arcuate, the inner border at basal half with four strong, elongate teeth, the basal of which is the shortest, anterior edentate portion about as long as the dentate part, acute at tips. Clypeus strongly carinate at middle, triangularly projecting in front and terminating in a blunt spine. Antennal scapes almost attaining occipital corners, thickened at anterior half and with a distinctly concave outline on inner surface before the tip; funiculus stout, gradually thickened toward apex, first joint twice as long as broad, second a little longer than broad, joints 3-10 transverse, terminal joint conical, as long as the two preceding joints together. Eyes small and flat, situated at anterior sixth of sides of head. Thorax long, slender, and nearly straight in profile. Pronotum longer than broad and widest behind middle, sides convex. Mesonotum half as long as pronotum and broader than long. Base of epinotum flat, more than twice as long as broad and much longer than the declivity, from which it is separated by an obtuse angle; surface of declivity fiat, sides obtusely margined. Petiole from above subcampanulate, sides little convex, posterior border broadly concave; in profile higher than long, a little higher behind than in front, not narrowed above, the broadly convex anterior surface rounding into the similarly convex dorsum; posterior surface shallowly concave, roundly margined at sides.

Body and appendages finely and very densely punctate and subopaque, the head in addition with coarser, separate and distinct punctures. Thorax with very sparse similar punctures. Clypeus with four coarse hairs at anterior margin, mandibles with sparse hairs, head, body and appendages with exceedingly fine pruinose pubescence.

Black, antennae, mandibles and legs reddish brown.

Type Material

Honduras: Choloma. Described from two workers found beneath a log. Cotypes. - Cat. No. 24438, National Museum of Natural History

References

- Aldana de la Torre, R. C.; Chacón de Ulloa, P. 1999. Megadiversidad de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la cuenca media del río Calima. Rev. Colomb. Entomol. 25: 37-47 (page 37, Record for Colombia)

- Aldana, R. C.; Chacón de Ulloa, P. 1995. Nuevos registros de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para Colombia. Bol. Mus. Entomol. Univ. Valle 3(2 2: 55-59 (page 55, record for Colombia)

- Baroni Urbani, C. 1975b. Contributo alla conoscenza dei generi Belonopelta Mayr e Leiopelta gen. n. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Mitt. Schweiz. Entomol. Ges. 48: 295-310 (page 309, combination in Leiopelta)

- Bolton, B. 1995b. A new general catalogue of the ants of the world. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 504 pp. (page 80, combination in Belonopelta; revived combination, catalogue)

- Esteves, F.A., Fisher, B.L. 2021. Corrieopone nouragues gen. nov., sp. nov., a new Ponerinae from French Guiana (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). ZooKeys 1074, 83–173 (doi:10.3897/zookeys.1074.75551).

- Mann, W. M. 1922. Ants from Honduras and Guatemala. Proc. U. S. Natl. Mus. 61: 1-54 (page 9, fig. 4 worker described)

- Richter, A., Boudinot, B.E., Hita Garcia, F., Billen, J., Economo, E.P., Beutel, R.G. 2023. Wonderfully weird: the head anatomy of the armadillo ant, Tatuidris tatusia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Agroecomyrmecinae), with evolutionary implications. Myrmecological News 33: 35-75 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_033:035).

- Varela-Hernández, F., Medel-Zosayas, B., Martínez-Luque, E.O., Jones, R.W., De la Mora, A. 2020. Biodiversity in central Mexico: Assessment of ants in a convergent region. Southwestern Entomologist 454: 673-686.

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1964b. The ant larvae of the subfamily Ponerinae: supplement. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 57: 443-462 (page 452, larva described)

- Wilson, E. O. 1955b. Ecology and behavior of the ant Belonopelta deletrix Mann (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Psyche (Camb.) 62: 82-87. (page 82, queen described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Baroni Urbani C. 1975. Contributo alla conoscenza dei generi Belonopelta Mayr e Leiopelta gen. n. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Mitt. Schweiz. Entomol. Ges. 48: 295-310.

- Brandao, C.R.F. 1991. Adendos ao catalogo abreviado das formigas da regiao neotropical (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Rev. Bras. Entomol. 35: 319-412.

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Goodnight, C. J., and M. L. Goodnight. 1956. Some observations in a tropical rain forest in Chiapas, Mexico. Ecology 37: 139-150.

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Longino J. T. 2013. Ants of Honduras. Consulted on 18 Jan 2013. https://sites.google.com/site/longinollama/reports/ants-of-honduras

- Longino J. T. L., and M. G. Branstetter. 2018. The truncated bell: an enigmatic but pervasive elevational diversity pattern in Middle American ants. Ecography 41: 1-12.

- Longino J. T., J. Coddington, and R. K. Colwell. 2002. The ant fauna of a tropical rain forest: estimating species richness three different ways. Ecology 83: 689-702.

- Longino J. T., and R. K. Colwell. 2011. Density compensation, species composition, and richness of ants on a neotropical elevational gradient. Ecosphere 2(3): 16pp.

- Longino J. et al. ADMAC project. Accessed on March 24th 2017 at https://sites.google.com/site/admacsite/

- Longino, J.T. 2010. Personal Communication. Longino Collection Database

- Maes, J.-M. and W.P. MacKay. 1993. Catalogo de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Nicaragua. Revista Nicaraguense de Entomologia 23.

- Patrick M., D. Fowler, R. R. Dunn, and N. J. Sanders. 2012. Effects of Treefall Gap Disturbances on Ant Assemblages in a Tropical Montane Cloud Forest. Biotropica 44(4): 472478.

- Quiroz-Robledo, L.N. and J. Valenzuela-Gonzalez. 2007. Distribution of poneromorph ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Mexican state of Morelos. Florida Entomologist 90(4):609-615

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133