Cyphomyrmex transversus

| Cyphomyrmex transversus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Cyphomyrmex |

| Species: | C. transversus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cyphomyrmex transversus Emery, 1894 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

DaRocha et al. (2015) studied the diversity of ants found in bromeliads of a single large tree of Erythrina, a common cocoa shade tree, at an agricultural research center in Ilhéus, Brazil. Forty-seven species of ants were found in 36 of 52 the bromeliads examined. Bromeliads with suspended soil and those that were larger had higher ant diversity. Cyphomyrmex transversus was found in 2 different bromeliads and was associated with the suspended soil and litter of the plants.

Identification

See the nomenclature section below.

Distribution

Kempf (1966) - Known to occur from northern Brazil to central Argentina. Being more xerophilous than the otherwise omnipresent Cyphomyrmex rimosus, it even occurs in the dry northeastern Brazil as the only representative of the genus.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 21.678819° to -31.632389°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Argentina, Brazil (type locality), Ecuador, Paraguay.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

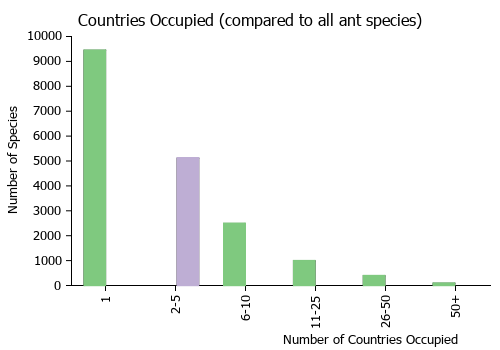

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Kempf (1966) - From my field experience in Agudos I have come to the conclusion that transversus nests in dryer situations (open fields, parkland) than Cyphomyrmex rimosus which prefers the more humid environment of dense woodlands. The distribution of the former seems to confirm this rule.

Bruch (1923) has studied and pictured the fungus-garden and nest of "pencosensis" in the Argentine. In fact, this ant cultivates a yeast-like fungus on excrements of insects, principally acridid grasshoppers, much as the typical rimosus and its allies.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 1 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 2 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 3 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 4 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 5 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 6 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 7 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 8 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- transversus. Cyphomyrmex rimosus subsp. transversus Emery, 1894c: 226 (w.q.) BRAZIL (Mato Grosso).

- Type-material: syntype workers, syntype queens (numbers not stated).

- Type-locality: Brazil: Mato Grosso (P. Germain).

- Type-depository: MSNG.

- Subspecies of rimosus: Forel, 1895b: 143; Emery, 1906c: 161; Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 723; Forel, 1908e: 69; Forel, 1912e: 188; Forel, 1915c: 358; Bruch, 1915: 529; Gallardo, 1916d: 324; Emery, 1924d: 342; Wheeler, W.M. 1925a: 45; Borgmeier, 1927c: 126; Santschi, 1931e: 278; Santschi, 1933e: 118; Weber, 1940a: 412 (in key); Kusnezov, 1949d: 442; Kusnezov, 1957b: 10 (in key); Weber, 1958d: 260.

- Status as species: Kempf, 1966: 193 (redescription); Kempf, 1972a: 94; Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 483 (in key); Brandão, 1991: 339; Bolton, 1995b: 168; Wild, 2007b: 33; Fernández & Serna, 2019: 850.

- Senior synonym of olindanus: Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 723; Wheeler, W.M. 1925a: 45; Weber, 1958d: 260; Kempf, 1966: 193; Kempf, 1972a: 94; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

- Senior synonym of pencosensis: Kempf, 1966: 193; Kempf, 1972a: 94; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

- Distribution: Argentina, Colombia, Brazil, Paraguay.

- olindanus. Cyphomyrmex rimosus r. olindanus Forel, 1901e: 337 (w.) BRAZIL (Pernambuco).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: Brazil: Olinda (M.J. Schmitt).

- Type-depositories: MCZC, MHNG.

- Junior synonym of transversus: Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 723; Wheeler, W.M. 1925a: 45; Weber, 1958d: 260; Kempf, 1966: 193; Kempf, 1972a: 94; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

- pencosensis. Cyphomyrmex rimosus var. pencosensis Forel, 1914d: 281 (w.) ARGENTINA (San Luis).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: Argentina: Alto Pencoso, nr La Plata (C. Bruch).

- Type-depository: MHNG.

- Santschi, 1931e: 278 (q.m.).

- As unavailable (infrasubspecific) name: Santschi, 1931e: 278; Santschi, 1933e: 118.

- Subspecies of rimosus: Bruch, 1915: 529; Bruch, 1916: 323; Gallardo, 1916d: 324; Bruch, 1923: 201; Emery, 1924d: 342; Weber, 1940a: 411 (in key); Kusnezov, 1949d: 441; Kusnezov, 1957b: 10 (in key); Weber, 1966: 168.

- Junior synonym of transversus: Kempf, 1966: 193; Kempf, 1972a: 94; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

Type Material

Kempf (1966) - Workers and a female, collected by P. Germain at an unidentified locality in Mato Grosso, Brazil, presumably in the Emery collection; not seen. One syntype worker of olindanus Forel received on loan from the MCZ. Types of pencosensis presumably in the Forel collection; not seen.

Taxonomic Notes

Kempf (1966) - The chief separatory characters between transversus and rimosus s. l. are given for the female in the diagnosis. The worker differs from Cyphomyrmex rimosus in the feeble and low pair of carinae on vertex; the distinctly dentate antero-inferior corner of pronotum; the low mesonotal ridges, as seen in profile, especially the posterior pair - both pairs encircling the slightly impressed disc much as in peltatus and dentatus; the rather shallow mesoepinotal constriction, appearing as an obtuse angle in profile; the two pairs of tubercles on the posterior corner of the basal face of epinotum; the strikingly transverse pedicelar nodes, principally the petiole; the deeply impressed middorsal groove on postpetiole; the long and hairless antero-median groove on tergum I of gaster; the body hairs which are thickly squamate, especially on head, thorax and gaster. Although due to variation proper to this group some of the aforesaid characters may occasionally fail to reach their full expression - or rimosus in one or the other specimen may imitate one or very few of the characters of transversus - their ensemble will always be sufficient to separate transversus from rimosus.

Description

Worker

Kempf (1966) - Total length 2.7-3.4 mm; head length 0.67-0.83 mm; head width 0.64-0.80 mm; thorax length 0.88-1.09 mm; hind femur length 0.69-0.83 mm. Uniformly yellowish brown to more or less fuscous brown; especially cephalic dorsum and gaster are occasionally more distinctly infuscated. Integument finely and densely punctate-granulate, opaque.

Head (fig 12). Mandibles reticulate-striolate and somewhat shining. Clypeus having the anterior border either straight or slightly concave, bearing on its corners a weak, blunt tooth. Frontal area impressed, without hairs. Frontal lobes semicircular, greatly expanded laterad; frontal carinae a bit sinuous and diverging caudad, attaining the slightly produced occipital corner. Midfrontal tumulus and transverse frontal groove extremely feeble; head disc nearly flat. Paired carinae on vertex blunt, low, extremely weak to vestigial. Preocular carina curving mesad above eye, not joining up with the feeble carina extending from the occipital lobe foreward to the postero-inferior border of eye. The latter with about 9-10 facets across its greatest diameter. Supraocular tubercle usually weak, contained in, and marked as a blunt angle of, the postocular carina. Inferior border of cheeks sharply marginate. Scape in repose surpassing the occipital corner by a distance subequal to its maximum width. Funicular segments II-IX not longer than broad; segment I a bit longer than II and III combined.

Thorax (fig 24). Pronotum dorsally with four tubercles, the median pair smallest; antero-inferior corner with a prominent tooth; sides of dorsal disc feebly marginate in front of the blunt, lateral tubercles. Mesonotum shallowly impressed, flanked by two pairs of low, ridge or welt-like tubercles; both the anterior and the posterior pair often fused to each other forming transverse, semicircular ridges, somehow imitating the condition obtained in peltatus and dentatus. Mesoepinotal constriction usually rather shallow in profile, forming an extremely blunt angle. Basal face of epinotum subquadrate, laterally bluntly marginate, each side bituberculate, the anterior tubercle obtuse, the posterior usually more prominent and tooth-like, situated below the level of basal face on the upper third of the declivous face. Basal third of hind femora gradually incrassate on flexor face, then forming an obtuse angle; the distal two thirds attenuate; posterior border of flexor face sharply marginate or even carinulate especially on bent.

Pedicel (fig 24, 30). Petiolar node strikingly transverse, about thrice as broad as long, lacking a dorsally produced crest and teeth on posterior border; strongly constricted in front of postpetiolar insertion. Postpetiole likewise rather broad, with a usually deeply impressed midlongitudinal groove and a shorter and broader groove posteriorly on each side. Tergum I of gaster with an antero-median groove, at least as long as petiole and hairless; lateral borders of same tergum distinctly marginate.

Body hairs squamate and reclinate, unusually short, thick and conspicuous on head, thoracic dorsum and gaster; narrow, squamate and appressed hairs on scapes and legs.

Queen

Kempf (1966) - Total length 3.5-4.2 mm; head length 0.80-0.93 mm; head width 0.76-0.88 mm; thorax length 1.09-1.33 mm; hind femur length 0.80-1.04 mm. This caste resembles quite closely that of Cyphomyrmex rimosus. The lateral ocelli, not prominent nor placed on raised ridges; the distinctly dentate antero-inferior corner of pronotum; the always well developed and salient epinotal spines; the striking width of the pedicelar segments, even better expressed in this caste than in the worker; the deep longitudinal furrow on the postpetiolar dorsum, distinguish transversus from rimosus. The squamate body hairs are of the same kind as in worker. Wings infuscated, venation as represented by Kusnezov (1949, pl. 1, fig. 15).

Male

Kempf (1966) - There is a scant diagnosis of this caste in Wheeler (1907: 724).

Karyotype

- n = 12, 2n = 24, karyotype = 14M+6SM+4A (French Guiana) (Aguiar et al., 2020).

- n = 21, 2n = 42, karyotype = 28M+14SM (Brazil) (Cardoso & Cristiano, 2021).

References

- Aguiar, H.J.A.C., Barros, L.A.C., Silveira, L.I., Petitclerc, F., Etienne, S., Orivel, J. 2020. Cytogenetic data for sixteen ant species from North-eastern Amazonia with phylogenetic insights into three subfamilies. Comparative Cytogenetics 14(1): 43–60 (doi:10.3897/CompCytogen.v14i1.46692).

- Albuquerque, E., Prado, L., Andrade-Silva, J., Siqueira, E., Sampaio, K., Alves, D., Brandão, C., Andrade, P., Feitosa, R., Koch, E., Delabie, J., Fernandes, I., Baccaro, F., Souza, J., Almeida, R., Silva, R. 2021. Ants of the State of Pará, Brazil: a historical and comprehensive dataset of a key biodiversity hotspot in the Amazon Basin. Zootaxa 5001, 1–83 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5001.1.1).

- Bruch, C. 1923. Estudios mirmecológicos con la descripción de nuevas especies de dípteros (Phoridae) por los Rr. Pp. H. Schmitz y Th. Borgmeier y de una araña (Gonyleptidae) por el Doctor Mello-Leitão. Rev. Mus. La Plata. 27:172-220.

- Cardoso, D. C., Cristiano, M. P. 2021. Karyotype diversity, mode, and tempo of the chromosomal evolution of Attina (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini): Is there an upper limit to chromosome number? Insects 1212, 1084 (doi:10.3390/insects12121084).

- da Silva, C.H.F., Arnan, X., Andersen, A.N., Leal, I.R. 2019. Extrafloral nectar as a driver of ant community spatial structure along disturbance and rainfall gradients in Brazilian dry forest. Journal of Tropical Ecology 35, 280–287 (doi:10.1017/s0266467419000245).

- DaRocha, W. D., S. P. Ribeiro, F. S. Neves, G. W. Fernandes, M. Leponce, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2015. How does bromeliad distribution structure the arboreal ant assemblage (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on a single tree in a Brazilian Atlantic forest agroecosystem? Myrmecological News. 21:83-92.

- Emery, C. 1894d. Studi sulle formiche della fauna neotropica. VI-XVI. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Ital. 26: 137-241 (page 226, worker, queen, male described)

- Franco, W., Ladino, N., Delabie, J.H.C., Dejean, A., Orivel, J., Fichaux, M., Groc, S., Leponce, M., Feitosa, R.M. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674, 509–543 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4674.5.2).

- Kempf, W. W. 1966 [1965]. A revision of the Neotropical fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex Mayr. Part II: Group of rimosus (Spinola) (Hym., Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 8: 161-200 (page 193, Raised to species, Senior synonym of pencosensis)

- Melo, T.S., Koch, E.B.A., Andrade, A.R.S., Travassos, M.L.O., Peres, M.C.L., Delabie, J.H.C. 2021. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in different green areas in the metropolitan region of Salvador, Bahia state, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology 82, e236269 (doi:10.1590/1519-6984.236269).

- Moura, M.N., Cardoso, D.C., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. The tight genome size of ants: diversity and evolution under ancestral state reconstruction and base composition. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa135 (doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa135).

- Ramos Lacau, L. de S.; Villemant, C.; Bueno, O. C.; Delabie, J. H. C.; Lacau, S. 2008. Morphology of the eggs and larvae of Cyphomyrmex transversus Emery (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini) and a note on the relationship with its symbiotic fungus. Zootaxa 1923:37-54.

- Wheeler, W. M. 1907d. The fungus-growing ants of North America. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 23: 669-807 (page 723, Senior synonym of olindanus)

- Wheeler, W. M. 1925a. Neotropical ants in the collections of the Royal Museum of Stockholm. Ark. Zool. 17A(8 8: 1-55 (page 45, Senior synonym of olindanus)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Bruch C. 1923. Estudios mirmecológicos con la descripción de nuevas especies de dípteros (Phoridae) por los Rr. Pp. H. Schmitz y Th. Borgmeier y de una araña (Gonyleptidae) por el Doctor Mello-Leitão. Revista del Museo de La Plata 27: 172-220.

- Castano-Meneses G., R. De Jesus Santos, J. R. Mala Dos Santos, J. H. C. Delabie, L. L. Lopes, and C. F. Mariano. 2019. Invertebrates associated to Ponerine ants nests in two cocoa farming systems in the southeast of the state of Bahia, Brazil. Tropical Ecology 60: 52–61.

- Delabie J. H. C., R. Céréghino, S. Groc, A. Dejean, M. Gibernau, B. Corbara, and A. Dejean. 2009. Ants as biological indicators of Wayana Amerindian land use in French Guiana. Comptes Rendus Biologies 332(7): 673-684.

- Dias N. S., R. Zanetti, M. S. Santos, J. Louzada, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2008. Interaction between forest fragments and adjacent coffee and pasture agroecosystems: responses of the ant communities (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Iheringia, Sér. Zool., Porto Alegre, 98(1): 136-142.

- Emery C. 1906. Studi sulle formiche della fauna neotropica. XXVI. Bullettino della Società Entomologica Italiana 37: 107-194.

- Fichaux M., B. Bechade, J. Donald, A. Weyna, J. H. C. Delabie, J. Murienne, C. Baraloto, and J. Orivel. 2019. Habitats shape taxonomic and functional composition of Neotropical ant assemblages. Oecologia 189(2): 501-513.

- Fleck M. D., E. Bisognin Cantarelli, and F. Granzotto. 2015. Register of new species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Rio Grande do Sul state. Ciencia Florestal, Santa Maria 25(2): 491-499.

- Forel A. 1908. Catálogo systemático da collecção de formigas do Ceará. Boletim do Museu Rocha 1(1): 62-69.

- Franco W., N. Ladino, J. H. C. Delabie, A. Dejean, J. Orivel, M. Fichaux, S. Groc, M. Leponce, and R. M. Feitosa. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674(5): 509-543.

- Gallardo A. 1916. Notes systématiques et éthologiques sur les fourmis attines de la République Argentine. Anales del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Buenos Aires 28: 317-344.

- Gallego-Ropero M.C., R.M. Feitosa & J.R. Pujol-Luz, 2013. Formigas (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) Associadas a Ninhos de Cornitermes cumulans Kollar (Isoptera, Termitidae) no Cerrado do Planalto Central do Brasil. EntomoBrasilis, 6(1): 97-101.

- Gibernau M., J. Orivel, J. H. C. Delabie, D. Barabe, and A. Dejean. 2007. An asymmetrical relationship between an arboreal ponerine ant and a trash-basket epiphyte (Araceae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 91: 341-346.

- Gomes E. C. F., G. T. Ribeiro, T. M. S. Souza, and L. Sousa-Souto. 2014. Ant assemblages (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in three different stages of forest regeneration in a fragment of Atlantic Forest in Sergipe, Brazil. Sociobiology 61(3): 250-257.

- Kempf W. W. 1966. A revision of the Neotropical fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex Mayr. Part II: Group of rimosus (Spinola) (Hym., Formicidae). Studia Entomologica 8: 161-200.

- Kempf W. W. 1978. A preliminary zoogeographical analysis of a regional ant fauna in Latin America. 114. Studia Entomologica 20: 43-62.

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Kusnezov N. 1949. El género Cyphomyrmex (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) en la Argentina. Acta Zoologica Lilloana 8: 427-456.

- Marinho C. G. S., R. Zanetti, J. H. C. Delabie, M. N. Schlindwein, and L. de S. Ramos. 2002. Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Diversity in Eucalyptus (Myrtaceae) Plantations and Cerrado Litter in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Neotropical Entomology 31(2): 187-195.

- Medeiros Macedo L. P., E. B. Filho, amd J. H. C. Delabie. 2011. Epigean ant communities in Atlantic Forest remnants of São Paulo: a comparative study using the guild concept. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 55(1): 7578.

- Miranda P. N., F. B. Baccaro, E. F. Morato, M. A. Oliveira. J. H. C. Delabie. 2017. Limited effects of low-intensity forest management on ant assemblages in southwestern Amazonian forests. Biodivers. Conserv. DOI 10.1007/s10531-017-1368-y

- Nascimento Santos M., J. H. C. Delabie, and J. M. Queiroz. 2019. Biodiversity conservation in urban parks: a study of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Rio de Janeiro City. Urban Ecosystems https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-019-00872-8

- Pereira M. C., J. H. C. Delabie, Y. R. Suarez, and W. F. Antonialli Junior. 2013. Spatial connectivity of aquatic macrophytes and flood cycle influence species richness of an ant community of a Brazilian floodplain. Sociobiology 60(1): 41-49.

- Pires de Prado L., R. M. Feitosa, S. Pinzon Triana, J. A. Munoz Gutierrez, G. X. Rousseau, R. Alves Silva, G. M. Siqueira, C. L. Caldas dos Santos, F. Veras Silva, T. Sanches Ranzani da Silva, A. Casadei-Ferreira, R. Rosa da Silva, and J. Andrade-Silva. 2019. An overview of the ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the state of Maranhao, Brazil. Pap. Avulsos Zool. 59: e20195938.

- Ramos L. S., R. Z. B. Filho, J. H. C. Delabie, S. Lacau, M. F. S. dos Santos, I. C. do Nascimento, and C. G. S. Marinho. 2003. Ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the leaf-litter in cerrado stricto sensu areas in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Lundiana 4(2): 95-102.

- Ramos L. de S., C. G. S. Marinho, R. Zanetti, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2003. Impacto de iscas formicidas granuladas sobre a mirmecofauna não-alvo em eucaliptais segundo duas formas de aplicacação / Impact of formicid granulated baits on non-target ants in eucalyptus plantations according to two forms of application. Neotropical Entomology 32(2): 231-237.

- Ramos L. de S., R. Zanetti, C. G. S. Marinho, J. H. C. Delabie, M. N. Schlindwein, and R. P. Almado. 2004. Impact of mechanical and chemical weedings of Eucalyptus grandis undergrowth on an ant community (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Rev. Árvore 28(1): 139-146.

- Ramos-Lacau L. S., P. S. D. Silva , S. Lacau , J. H. C. Delabie, and O. C. Bueno. 2012. Nesting architecture and population structure of the fungus-growing ant Cyphomyrmex transversus (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini) in the Brazilian coastal zone of Ilhéus, Bahia, Annales de la Société entomologique de France (N.S.): International Journal of Entomology. 48(3-4): 439-445.

- Santos M. P. C. J., A. F. Carrano-Moreira, and J. B. Torres. 2012. Diversity of soil ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in dense Atlantic Forest and sugarcane plantationsin the County of Igarassu-PE. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Agrárias 7(4): 648-656.

- Santos M. S., J. N. C. Louzada, N. Dias, R. Zanetti, J. H. C. Delabie, and I. C. Nascimento. 2006. Litter ants richness (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in remnants of a semi-deciduous forest in the Atlantic rain forest, Alto do Rio Grande region, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Iheringia, Sér. Zool., Porto Alegre, 96(1): 95-101.

- Santos P. P., A. Vasconcelos, B. Jahyny, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2010. Ant fauna (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) associated to arboreal nests of Nasutitermes spp. (Isoptera, Termitidae) in a cacao plantation in southeastern Bahia, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 54(3): 450-454.

- Santschi F. 1925. Fourmis des provinces argentines de Santa Fe, Catamarca, Santa Cruz, Córdoba et Los Andes. Comunicaciones del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural "Bernardino Rivadavia" 2: 149-168.

- Santschi F. 1931. Contribution à l'étude des fourmis de l'Argentine. Anales de la Sociedad Cientifica Argentina. 112: 273-282.

- Santschi F. 1933. Fourmis de la République Argentine en particulier du territoire de Misiones. Anales de la Sociedad Cientifica Argentina. 116: 105-124.

- Silva F. H. O., J. H. C. Delabie, G. B. dos Santos, E. Meurer, and M. I. Marques. 2013. Mini-Winkler Extractor and Pitfall Trap as Complementary Methods to Sample Formicidae. Neotrop Entomol 42: 351358.

- Siqueira de Castro F., A. B. Gontijo, P. de Tarso Amorim Castro, and S. Pontes Ribeiro. 2012. Annual and Seasonal Changes in the Structure of Litter-Dwelling Ant Assemblages (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Atlantic Semideciduous Forests. Psyche doi:10.1155/2012/959715

- Sobrinho T., J. H. Schoereder, C. F. Sperber, and M. S. Madureira. 2003. Does fragmentation alter species composition in ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)? Sociobiology 42(2): 329-342.

- Suguituru S. S., M. Santina de Castro Morini, R. M. Feitosa, and R. Rosa da Silva. 2015. Formigas do Alto Tiete. Canal 6 Editora 458 pages

- Ulyssea M. A., and C. R. F. Brandao. 2013. Ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the seasonally dry tropical forest of northeastern Brazil: a compilation from field surveys in Bahia and literature records. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 57(2): 217224.

- Ulysséa M. A., C. R. F. Brandão. 2013. Ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the seasonally dry tropical forest of northeastern Brazil: a compilation from field surveys in Bahia and literature records. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 57(2): 217-224.

- Vargas A. B., A. J. Mayhé-Nunes, J. M. Queroz, G. O. Souza, and E. F. Ramos. 2007. Effects of Environmental Factors on the Ant Fauna of Restinga Community in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Neotropical Entomology 36(1): 028-037

- Vittar, F. 2008. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la Mesopotamia Argentina. INSUGEO Miscelania 17(2):447-466

- Vittar, F., and F. Cuezzo. "Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la provincia de Santa Fe, Argentina." Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina (versión On-line ISSN 1851-7471) 67, no. 1-2 (2008).

- Weber N. A. 1958. Some attine synonyms and types (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 60: 259-264.

- Wheeler W. M. 1907. The fungus-growing ants of North America. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 23: 669-807.

- Wheeler W. M. 1925. Neotropical ants in the collections of the Royal Museum of Stockholm. Arkiv för Zoologi 17A(8): 1-55.

- Wild, A. L.. "A catalogue of the ants of Paraguay (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)." Zootaxa 1622 (2007): 1-55.

- da Silva Araujo, M., Castro Della Lucia, T.M., DA VEIGA, Clayton E y CARDOSO DO NASCIMENTO, Ivan. 2004. Efeito da queima da palhada de cana-de-açúcar sobre comunidade de formicídeos. Ecol. austral. 14(2): 191-200.

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Need species key

- Tropical

- South subtropical

- Diapriid wasp Associate

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 1

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 2

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 3

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 4

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 5

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 6

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 7

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 8

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Myrmicinae

- Attini

- Cyphomyrmex

- Cyphomyrmex transversus

- Myrmicinae species

- Attini species

- Cyphomyrmex species

- Ssr