Mycetophylax bigibbosus

| Mycetophylax bigibbosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycetophylax |

| Species: | M. bigibbosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycetophylax bigibbosus (Emery, 1894) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

A rainforest species that nests in rotting wood.

Identification

Kempf (1964) - The head of the bigibbosus worker is strikingly similar to that of Mycetophylax strigatus, but the configuration of the thorax, the pedicel and the gaster shows clearly the conspicuous differences between both species.

Distribution

Known from Brazil and British Guiana.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 11.25° to -2.416667°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Brazil (type locality), French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

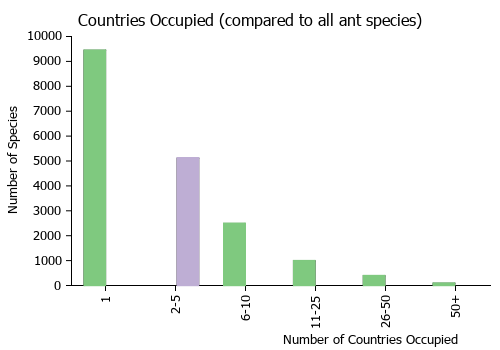

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

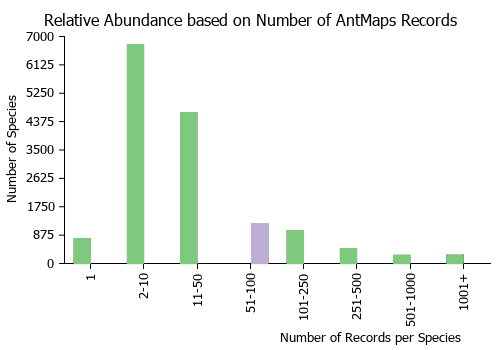

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Kempf (1964) summarized Weber's (1946) account of the synonymized subspecies tumulus:

M. bigibbosus is a rain forest species and seems to prefer high humidities. The nest chambers were found in rotted wood, mostly in excavate cells, but also under bark. The cavity size is variable but averages about 20-25 cc. The fungus garden is mostly sessile, resting on the floor, but variously attached at the sides. Occasionally the chains of fungus garden are also suspended from the ceiling. The substrate is heterogeneous, consisting mainly of yellow to brown particles, often of woody consistency; once even a head of a Dolichoderus ant was used as substrate. Once a worker of Prionopelta punctulata was found inside a nest, preying perhaps on the larvae of M. bigibbosus. The finding of an dealate queen in a tiny fungus garden, with a full grown worker, suggests splitting as a possible means of colony foundation.

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- bigibbosus. Cyphomyrmex bigibbosus Emery, 1894c: 226 (w.) BRAZIL.

- Wheeler, G.C. 1949: 670 (l.).

- Combination in Mycetophylax: Sosa-Calvo et al., 2017: 9.

- Senior synonym of tumulus: Kempf, 1972a: 92.

- See also: Kempf, 1964d: 20.

- tumulus. Cyphomyrmex bigibbosus subsp. tumulus Weber, 1938b: 185 (w.q.m.) GUYANA.

- Junior synonym of bigibbosus: Kempf, 1964d: 20.

- Revived from synonymy and raised to species: Weber, 1966: 167.

- Junior synonym of bigibbosus: Kempf, 1972a: 92.

Description

Worker

Kempf (1964) - Total length 3.2-3.4 mm; head length 0.75-0.83 mm; head width 0.67-0.75 mm; thorax length 0.93-1.04 mm; hind femur length 0.83-0.91 mm. Fuscous reddish brown; head usually darkest; mandibles, coxae, femora and sometimes also thorax light brown. Integument, including antennal scrobe, densely granular and opaque.

Head (fig 2). - Mandibles with 7-8 teeth. Clypeus: anterior border mesially excised; central portion of c1ypeus obliquely raised towards front, with two acute teeth next to origin of frontal lobes. Vertex with a pair of short carinules. Supraocular tumulus blunt, rounded, not prominent. Preocular carinae reaching the gently produced occipital lobes, closing completely the antennal scrobe. Lower border of sides of head carinate. Antennal scapes, in repose, not projecting beyond tip of occipital lobes. Only funicular segments 1 and 10 distinctly longer than broad.

Thorax (fig 16). - Pronotum: the single median tubercle quite distinct, the lateral ones very low and blunt, continued foreward as a faint, often more or less obsolete, margination that separates the pronotal dorsum from the sides: antero-inferior corner acutely dentate. Mesonotum: anterior pair of tubercles prominent and conical, posterior pair very low but distinct and blunt. Mesoepinotal constriction conspicuous but relatively shallow in profile. Epinotum completely rounded and unarmed. Hind femora a little dilated ventrally but not visibly carinate posteriorly at basal third.

Pedicel (fig 16, 30). - Petiole in dorsal view rather longer than broad, anterior corners of node not sharply angulate, dorsal ridges at best vestigial, posterior dorsal border without a raised carinule. Postpetiole, in dorsal view, subquadrate not transverse, with a perpendicular anterior face, a rather flat dorsal face, having the posterior border deeply excised between a pair of prominent horizontal tubercles. Tergum I of gaster strongly vaulted, lacking lateral margination and longitudinal carinae. Hairs minute, appressed, glittering, scattered; quite inconspicuous, on body and appendages.

Queen

Kempf (1964) - Total length 3.8 mm; head length 0.84 mm; head width 0.79 mm; thorax length 1.20 mm; hind femur length 0.96 mm. Resembling the worker with the differences of the caste. Differs from Mycetophylax faunulus in the following features: Bicolored, head and gaster fuscous, thorax brown. Occipital lobes much less projecting both in full-face view as in profile, much as in worker. Midpronotal tubercle faint but still distinguishable. Pair of anterior tubercles between arms of Mayrian furrows very low; scutum laterally not deeply furrowed. Paraptera postero-laterally with a short tooth. Posterior scutellar teeth much shorter, about as long as their width at base. Epinotal teeth completely absent. Pedicel as in worker; petiole elongate, with subparallel sides, anterior corners rather rounded; postpetiole with the same deep mesial excision on posterior border, flanked by prominent lobes, as in worker. Gaster bigibbous on anterior third of tergum I.

Male

Weber (1938), as tumulus

Type Material

Kempf (1964) - The lone holotype worker of bigibbosus is in the Emery collection at the "Museo Civico di Storia Naturale", Genova, Italy; not seen. Syntypes of tumulus: 3 workers examined (MCZ, NAW).

References

- Albuquerque, E., Prado, L., Andrade-Silva, J., Siqueira, E., Sampaio, K., Alves, D., Brandão, C., Andrade, P., Feitosa, R., Koch, E., Delabie, J., Fernandes, I., Baccaro, F., Souza, J., Almeida, R., Silva, R. 2021. Ants of the State of Pará, Brazil: a historical and comprehensive dataset of a key biodiversity hotspot in the Amazon Basin. Zootaxa 5001, 1–83 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5001.1.1).

- Emery, C. 1894d. Studi sulle formiche della fauna neotropica. VI-XVI. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Ital. 26: 137-241 (page 226, worker described)

- Franco, W., Ladino, N., Delabie, J.H.C., Dejean, A., Orivel, J., Fichaux, M., Groc, S., Leponce, M., Feitosa, R.M. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674, 509–543 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4674.5.2).

- Kempf, W. W. 1964d. A revision of the Neotropical fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex Mayr. Part I: Group of strigatus Mayr (Hym., Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 7: 1-44 (page 20, see also)

- Kempf, W. W. 1972b. Catálogo abreviado das formigas da regia~o Neotropical. Stud. Entomol. 15: 3-344 (page 92, Senior synonym of tumulus)

- Sosa-Calvo, J., JesÏovnik, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci, M. Jr., Schultz, T.R. 2017. Rediscovery of the enigmatic fungus-farming ant "Mycetosoritis" asper Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Implications for taxonomy, phylogeny, and the evolution of agriculture in ants. PLoS ONE 12: e0176498 (DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0176498).

- Weber, N. A. 1946. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part IX. The British Guiana species. Rev. Entomol. (Rio de Janeiro). 17:114-172.

- Wheeler, G. C. 1949 [1948]. The larvae of the fungus-growing ants. Am. Midl. Nat. 40: 664-689 (page 670, larva described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Franco W., N. Ladino, J. H. C. Delabie, A. Dejean, J. Orivel, M. Fichaux, S. Groc, M. Leponce, and R. M. Feitosa. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674(5): 509-543.

- Groc S., J. H. C. Delabie, F. Fernandez, M. Leponce, J. Orivel, R. Silvestre, Heraldo L. Vasconcelos, and A. Dejean. 2013. Leaf-litter ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a pristine Guianese rainforest: stable functional structure versus high species turnover. Myrmecological News 19: 43-51.

- Groc S., J. Orivel, A. Dejean, J. Martin, M. Etienne, B. Corbara, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2009. Baseline study of the leaf-litter ant fauna in a French Guianese forest. Insect Conservation and Diversity 2: 183-193.

- Kempf W. W. 1959. Insecta Amapaensia. - Hymenoptera: Formicidae. Studia Entomologica (n.s.)2: 209-218.

- Kempf W. W. 1964. A revision of the Neotropical fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex Mayr. Part I: Group of strigatus Mayr (Hym., Formicidae). Studia Entomologica 7: 1-44.

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Kusnezov N. 1953. La fauna mirmecológica de Bolivia. Folia Universitaria. Cochabamba 6: 211-229.

- Mayhe-Nunes A. J., and K. Jaffe. 1998. On the biogeography of attini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ecotropicos 11(1): 45-54.

- Medeiros Macedo L. P., E. B. Filho, amd J. H. C. Delabie. 2011. Epigean ant communities in Atlantic Forest remnants of São Paulo: a comparative study using the guild concept. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 55(1): 7578.

- Weber N. A. 1938. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part IV. Additional new forms. Part V. The Attini of Bolivia. Rev. Entomol. (Rio J.) 9: 154-206.

- Weber N. A. 1945. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part VIII. The Trinidad, B. W. I., species. Revista de Entomologia (Rio de Janeiro) 16: 1-88.

- Weber N. A. 1946. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part IX. The British Guiana species. Revista de Entomologia (Rio de Janeiro) 17: 114-172.

- Weber, Neal A. 1968. Tobago Island Fungus-growing Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 79:141-145.

- Weber, Neal A. 1968. Tobago Island Fungus-growing Ants. Entomological News. 79(6): 141-145.

- Weber, Neil A. 1968. Tobago Island Fungus-growing Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 79(6):141-145.