Mycetophylax lectus

| Mycetophylax lectus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycetophylax |

| Species: | M. lectus |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycetophylax lectus (Forel, 1911) | |

This species is only known from two collections.

Identification

See the description below.

Distribution

Aside from the type series, this species has also been recorded by Santschi (1925: 164) from Fives Lille, in Santa Fé Province, Argentina. I have not seen these specimens (Kempf 1964).

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: -19.08333333° to -31.632389°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Argentina, Brazil (type locality), Paraguay.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

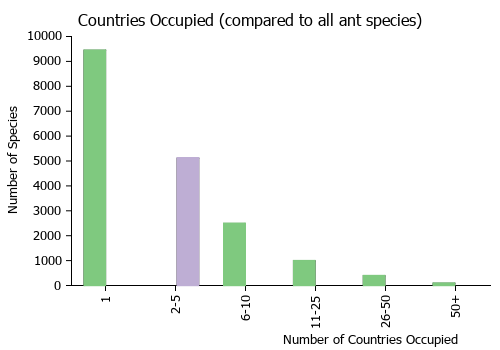

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Kempf (1964) - According to Luederwaldt (1926: 267) the nest of this species was found in an open field (same habitat as Mycocepurus goeldii). The cavities were subspherical. The fungus garden is sessile.

Ramos-Lacau et al. (2015) studied Mycetophylax lectus in a transitional area (savanna-forest) between Atlantic forest and cerrado (Brazilian savanna) disturbed by an annual fire regime, in Southeast Brazil. Colonies were located in June 2005 after a bushfire. Eight nests were excavated, five in June and three in October. They found:

Colonies were aggregated and located relatively close to each other, with a mean distance between them of 3.38 ± 2.75 m. The external nest structure of the ant consisted of a single circular nest entrance hole with mean diameter of 0.21 ± 0.06 cm but without a well-formed nest mound on the ground surface. The diameter of nest-entrance hole varied significantly between colonies (t test = 8.22; p < 0.001). The internal structure was formed by a single oval chamber connected to the outside via a single gallery. A yeast-like fungi forming a spongy mass was observed and disposed at the bottom of the chamber. No dedicated garbage chamber was observed in all studied colonies.

Gallery length varied from 8.5 to 17 cm with mean length of 11 ± 3 cm. Mean chamber depth varied from 2 to 3.8cm reaching a mean of 3.05 ± 0.6 cm. Chamber volume varied from 8.2 to 54.3 cm³ with average value of 27.5 ± 15.1 cm³.

These measured nest attributes varied significantly between colonies (i.e. gallery length: T test = 9.7 and p < 0.001; chamber depth: T test = 13.4 and p < 0.001; and chamber volume: T test = 4.8 and p = 0.003). Two other species of the Cyphomyrmex genus (i.e. Mycetophylax strigatus and Cyphomyrmex rimosus) were simultaneously observed in the area with similar patterns of external nest architecture of C. lectus. For C. lectus colonies, the mean number of workers was of 70 ± 49.4 individuals per colony. No significant effect of total number of ant individuals (i.e., colony size) on both gallery length (F= 0.059, g.l. = 1; p= 0.83; Fig 1A) and nest chamber volume (F= 0.22, g.l. = 1; p = 0.65; Fig 1B) was observed but the nest chamber depth increased significantly with increasing the number of ants per colony (F= 7.88, g.l. = 1; P = 0.04; Fig 1C). Ant number per colony explained 54% of the observed variation regarding the chamber depth. As observed to all studied nest attributes, the number of ant individuals also varied significantly between colonies (T test = 4.83 and p = 0.003).

Alates (young reproductive females and males), larvae and pupae were found only in one colony (sampled in October). This colony contained eight females, two males, three larvae and nine pupae. None of the eight investigated colonies contained eggs. A single dealate queen was observed in each eight studied colonies strongly suggesting that this species is monogynous.

Castes

Queen and male are unknown.

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- lectus. Atta (Cyphomyrmex) olitrix subsp. lecta Forel, 1911c: 295 (w.) BRAZIL.

- Combination in Cyphomyrmex: Luederwaldt, 1918: 39.

- Combination in Mycetophylax: Sosa-Calvo et al., 2017: 9.

- Raised to species: Kempf, 1964d: 36.

Description

Kempf (1964) - The broadly expanded frontal carinae, the foliaceous carina on postero-inferior corner of head, the huge inferior pronotal spine, the unarmed epinotum, vouch for specific distinction from Mycetophylax olitor. The species seems more closely related with Mycetophylax nemei and perhaps Mycetophylax vallensis.

Worker

Kempf (1964) - (lectotype and paratypes). - Total length 2.7-2.8 mm; head length 0.64-0.67 mm; head width 0.59-0.61 mm; thorax length 0.80-0.83 mm; hind femur length 0.59-0.61 mm. Yellowish brown; front of head ferruginous; legs rather pale.

Head (fig 12). Mandibles finely reticulate-punctate and vestigially striolate; chewing border with 7 teeth; apical tooth prominent. Anterior clypeal border slightly notched in the middle, laterally with a small tooth. Frontal area more or less distinct and impressed. Frontal lobes greatly expanded laterad, covering in full-face view part of the eyes, anteriorly rounded, then diverging caudad and somewhat sinuous, rounded behind before the gentle constriction; frontal carinae prolonged caudad, slightly diverging, joining the narrowly crested preocular carina to close the antennal scrobe at the scarcely drawn-out occipital corner. Occiput broadly but gently emarginate, with another median and deeper emargination between the short and inconspicuous carinae of the vertex. Supraocular tumulus feeble and indistinct. Inferior border of cheeks immarginate, except for a short and low foliaceous carina in front of the inferior occipital corner. Scapes in repose not surpassing the occipital corner. Funicular segments II-VIII not longer than broad.

Thorax (fig 14). Midpronotal tooth feeble and indistinct, lateral teeth low and subconical, antero-inferior corner with a very long tooth pointing foreward. Mesonotum flat to slightly excavate, flanked by the anterior and posterior pair of very low tubercles, which clearly separate the dorsum from the sides. Mesoepinotal suture distinct, but only gently impressed. Basal face of epinotum much shorter than the laterally immarginate declivous face, posteriorly unarmed. Inferior borders of femora faintly crested; hind femora gradually increasing in depth toward basal third, forming ventrally an angle, the postero-inferior border being armed at this place with a prominent foliaceous flange.

Pedicel (fig 14). Note the narrow postero-median laminule flanked by short longitudinal carinules. Postpetiole cupuliform, dorsally flattened; lateral lobes with foliaceous margin, not appressed. Tergum I of gaster with marginate anterior border, laterally immarginate, mesially not impressed.

Integument densely granulate, opaque, with sparser small setigerous pits. Hairs minute, completely appressed. Gular face of head and sternum I of gaster with curved subdecumbent hairs.

Type Material

Kempf (1964) - 14 workers taken by H. Luederwaldt in the borough of lpiranga in São Paulo City, in 1909 (MHNG, DZSP, WWK).

References

- Albuquerque, E., Prado, L., Andrade-Silva, J., Siqueira, E., Sampaio, K., Alves, D., Brandão, C., Andrade, P., Feitosa, R., Koch, E., Delabie, J., Fernandes, I., Baccaro, F., Souza, J., Almeida, R., Silva, R. 2021. Ants of the State of Pará, Brazil: a historical and comprehensive dataset of a key biodiversity hotspot in the Amazon Basin. Zootaxa 5001, 1–83 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5001.1.1).

- Forel, A. 1911e. Ameisen des Herrn Prof. v. Ihering aus Brasilien (Sao Paulo usw.) nebst einigen anderen aus Südamerika und Afrika (Hym.). Dtsch. Entomol. Z. 1911: 285-312 (page 295, worker described)

- Kempf, W. W. 1964d. A revision of the Neotropical fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex Mayr. Part I: Group of strigatus Mayr (Hym., Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 7: 1-44 (page 36, Raised to species)

- Lopes, L.L., Mariano, C.S.F., Delabie, J.H.C., Silva, J.G. 2022. First cytogenetic study through conventional staining of the ant genus Blepharidatta Wheeler, 1915 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Attini). Sociobiology 69(4), e7843 (doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v69i4.7843).

- Luederwaldt, H. 1918. Notas myrmecologicas. Rev. Mus. Paul. 10: 29-64 (page 39, Combination in Cyphomyrmex)

- Luederwaldt, H. 1926. Observações biologicas sobre formigas brasileiras especialmente do estado de São Paulo. Rev. Mus. Paul. 14:185-303.

- Ramos-Lacau, L. S., P. S. D. Silva, J. H. C. Delabie, S. Lacau, and O. C. Bueno. 2015. Nest Biology and Demography of the Fungus-Growing Ant Cyphomyrmex lectus Forel (Myrmicinae: Attini) at a Disturbed Area Located in Rio Claro-SP, Brazil. Sociobiology. 62:462-466. doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v62i3.709

- Santschi, F. 1925. Fourmis des provinces argentines de Santa Fe, Catamarca, Santa Cruz, Córdoba et Los Andes. Comun. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. "Bernardino Rivadavia". 2:149-168.

- Sosa-Calvo, J., JesÏovnik, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci, M. Jr., Schultz, T.R. 2017. Rediscovery of the enigmatic fungus-farming ant "Mycetosoritis" asper Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Implications for taxonomy, phylogeny, and the evolution of agriculture in ants. PLoS ONE 12: e0176498 (DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0176498).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Kempf W. W. 1964. A revision of the Neotropical fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex Mayr. Part I: Group of strigatus Mayr (Hym., Formicidae). Studia Entomologica 7: 1-44.

- Silvestre R., M. F. Demetrio, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2012. Community Structure of Leaf-Litter Ants in a Neotropical Dry Forest: A Biogeographic Approach to Explain Betadiversity. Psyche doi:10.1155/2012/306925

- Soares S. A., W. F. Antoniali Junior, and S. E. Lima-Junior. 2010. Diversidade de formigas epigéicas (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) em dois ambientes no Centro-Oeste do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 54(1): 7681.

- Vittar, F. 2008. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la Mesopotamia Argentina. INSUGEO Miscelania 17(2):447-466

- Wild, A. L. "A catalogue of the ants of Paraguay (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)." Zootaxa 1622 (2007): 1-55.