Mycocepurus curvispinosus

| Mycocepurus curvispinosus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycocepurus |

| Species: | M. curvispinosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycocepurus curvispinosus Mackay, W.P., 1998 | |

Most specimens have been collected in pitfall traps, or litter samples. This species apparently lives in nests of Mycocepurus smithii in México (La Mancha, Veracruz). The workers are slow and timid and forage together with those of M. smithii. A single, dealate female was collected in Panamá on 18-v-1995. (Mackay et al. 2004)

Identification

The worker of this species is easily recognized, as it lacks anterior pronotal spines. Additionally, the propodeal spines are strongly curved upwards. No other species in the genus has this combination of characters. The female can be recognized by the large lateral pronotal spines, and the slightly upturned propodeal teeth. It is relatively small (total length slightly more than 2.5 mm), smaller than the females of Mycocepurus smithii. The first two characteristics easily separate this species from M. smithii. (Mackay et al. 2004)

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 19.6083° to 6.684167°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Costa Rica (type locality), Mexico, Panama.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

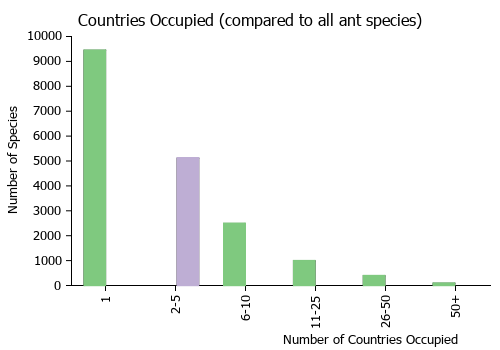

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Habitat

Found in a variety of communities, ranging from slashed and burned areas, sub-deciduous forests to tropical rain forests.

Biology

|

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- curvispinosus. Mycocepurus curvispinosus Mackay, W.P., 1998c: 423, figs. 5, 6, 9 (w.) COSTA RICA.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Queen

Mackay et al. (2004) - Head length (HL, anterior edge of median lobe of clypeus to midpoint of posterior margin) 0.71, head width (HW, maximum, at posterior edge of eye) 0.67, scape length (SL, excluding basal condyle) 0.58, eye length (maximum) 0.17, Weber’s length (anterior border of pronotum to posterior angle of metapleuron) 1.07, cephalic index (HL/HW X 100) 95, scape index (SL/HL X 100) 81.

Mandible apparently with 5 teeth; frontal lobes expanded, covering insertions of antennae; sides of head nearly parallel, slightly narrowed in region of eyes, which extend past sides of head; posterior margin of head concave, occipital spines poorly developed; scape barely reaches posterior lateral corner; lateral pronotal spine welldeveloped, with wide base, inferior lateral pronotal spine poorly developed; scutellum angulate posteriorly, overhanging metanotum; propodeal spines well-developed, slightly upturned, with broad base; subpeduncular process poorly developed, peduncle elongated, apex of petiole with two sets of spines.

Anterior margin of clypeus with several, erect hairs, dorsum of head with several, erect hairs, hairs on scape decumbent, dorsum of mesosoma with erect hairs, petiole nearly lacking erect hairs, postpetiole and gaster with abundant, erect hairs, hairs on tibiae mostly suberect.

Entire ant very roughly sculptured, except for mandibles, which are striate and moderately shining, much of rough sculpture, especially on dorsum of gaster, arranged in poorly defined striate.

Ferrugineous red.

References

- Mackay, W. P. 1998c. Dos especies nuevas de hormigas de la tribu Attini de Costa Rica y México: Mycetosoritis vinsoni y Mycocepurus curvispinosus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Rev. Biol. Trop. 46: 421-426 (page 423, figs. 5, 6, 9 worker described)

- Mackay, W. P.; Maes, J.-M.; Fernández, Patricia Rojas; Luna, G. 2004. The ants of North and Central America: the genus Mycocepurus (Hymenoptera : Formicidae). Journal of Insect Science (Tucson) 4(27): 1-7. (page 4, queen described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Achury R., and A.V. Suarez. 2017. Richness and composition of ground-dwelling ants in tropical rainforest and surrounding landscapes in the Colombian Inter-Andean valley. Neotropical Entomology https://doi.org/10.1007/s13744-017-0565-4

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Klingenberg, C. and C.R.F. Brandao. 2005. The type specimens of fungus growing ants, Attini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Myrmicinae) deposited in the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil. Papeis Avulsos de Zoologia 45(4):41-50

- Mackay, W.P. 1998. Dos especies nuevas de hormigas de la tribu Attini de Costa Rica y México: Mycetosoritis vinsoni y Mycocepurus curvispinosus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Revista de Biología Tropical46(2)

- Mackay, W.P., J.-P. Maes, P. Rojas Fernandez and G. Luna. 2004. The ants of North and Central America: the genus Mycocepurus (Hymentopera: Formicidae). Journal of Insect Science 4:27.

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133