Octostruma trithrix

| Octostruma trithrix | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Octostruma |

| Species: | O. trithrix |

| Binomial name | |

| Octostruma trithrix Longino, 2013 | |

In the southern portion of its range, Octostruma trithrix occurs in a variety of forested habitats: wet to seasonal dry, second growth to mature. It is typically lowland, occurring from sea level to around 700 m. In the northern part of the range it occurs in cloud forest, up to 1200 m elevation. Almost all collections are from Berlese and Winkler samples of sifted litter and rotten wood from the forest floor. In quantitative 1 m2 litter plot samples, within-sample abundance is tens of workers or fewer, but the species can occur frequently, suggesting a high density of small colonies. Dealate queens may occur together with workers in litter samples. (Longino 2013)

Identification

Longino (2013) - Mandible with 8 teeth, tooth 1 a broad blunt lamella, strongly differentiated from tooth 2, teeth 2–5 acute, similar in shape, with denticles between them; teeth 5–8 forming an apical fork, with 5 and 8 large, 6 and 7 small partially confluent denticles (O. balzani complex); face setation, erect setae present on posterolateral margins of head (absent in Octostruma amrishi and Octostruma gymnogon); in most workers of a series, a seta present between anterior seta on side of head near eye and medial vertex seta (this seta typically absent in Octostruma balzani, O. megabalzani, O. amrishi, and O. gymnogon); mesosomal dorsum with one pair of erect setae (absent in O. amrishi, O. gymnogon; 2 pairs in Octostruma lutzi); metanotal groove not impressed in profile view (impressed in O. balzani and O. megabalzani).

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Northern Mexico (Nuevo Leon) to Honduras.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 25.189293° to 15.5123738°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

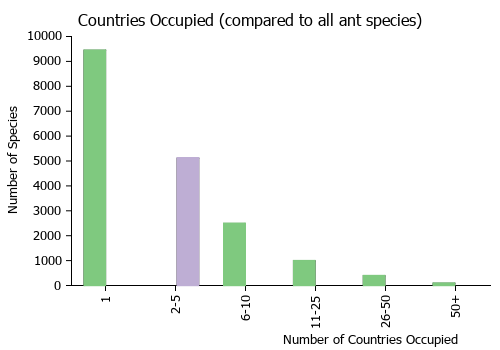

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

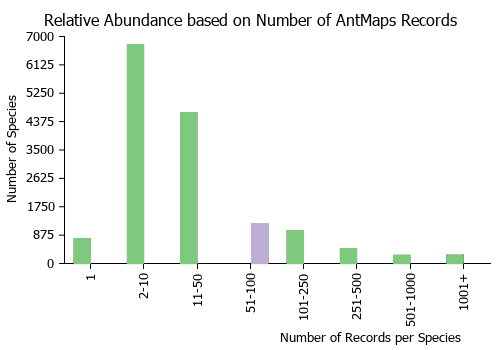

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- trithrix. Octostruma trithrix Longino, 2013: 54, figs. 1E, 3D, 5A, 8A, 40, 42 (w.q.) MEXICO.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

HW 0.54–0.62, HL 0.50–0.58, WL 0.52–0.66, CI 102–112 (n=7). Matching in almost every respect the description for Octostruma balzani, except the differences outlined in the Diagnosis and key. In addition to characters in the Diagnosis, first gastral tergite typically with 8–16 erect setae, color red brown.

Queen

HW 0.59–0.64, HL 0.55–0.60, WL 0.70–0.75, CI 103–107 (n=7). Similar to O. balzani in most respects; 4–6 setae across vertex between compound eyes (2–4 in O. balzani); postpetiolar disc with 4–6 erect setae (2–4 in O. balzani).

Type Material

Holotype worker: Mexico, Chiapas: 8 km SE Salto de Agua, 17.51611, -92.30168, ±50 m, 100 m, 14 Jun 2008, 2º wet forest, ex sifted leaf litter (LLAMA, Wa-A-08-2-03) California Academy of Sciences, CASENT0639179. Paratype workers, queen: same data University of California, Davis, CASENT0639180; Colección de Artrópodos, CASENT0639181; Escuela Agricola Panamericana, CASENT0639182; CASC, CASENT0639183; John T. Longino Collection, CASENT0639184; same data except 17.51442, -92.29500, ±50 m, 70 m (LLAMA, Wa-A-08-1-05) Colección Entomológica de El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, CASENT0639174; National Museum of Natural History, CASENT0639175; Museum of Comparative Zoology, CASENT0639176; Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, CASENT0639177; CASC, CASENT0639178.

Etymology

The name refers to anterior row of three spatulate setae on the face. It is a noun in apposition and thus invariant.

References

- Ahuatzin, D.A., González-Tokman, D., Valenzuela-González, J.E., Escobar, F., Ribeiro, M.C., Acosta, J.C.L., Dáttilo, W. 2021. Sampling bias in multiscale ant diversity responses to landscape composition in a human-disturbed rainforest. Insectes Sociaux (doi:10.1007/s00040-021-00844-2).

- Longino, J.T. 2013. A revision of the ant genus Octostruma Forel 1912 (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Zootaxa 3699, 1-61. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3699.1.1

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Ahuatzin D. A., E. J. Corro, A. Aguirre Jaimes, J. E. Valenzuela Gonzalez, R. Machado Feitosa, M. Cezar Ribeiro, J. Carlos Lopez Acosta, R. Coates, W. Dattilo. 2019. Forest cover drives leaf litter ant diversity in primary rainforest remnants within human-modified tropical landscapes. Biodiversity and Conservation 28(5): 1091-1107.

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Longino J. T. L., and M. G. Branstetter. 2018. The truncated bell: an enigmatic but pervasive elevational diversity pattern in Middle American ants. Ecography 41: 1-12.

- Longino J. et al. ADMAC project. Accessed on March 24th 2017 at https://sites.google.com/site/admacsite/