Trachymyrmex pakawa

| Trachymyrmex pakawa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Trachymyrmex |

| Species: | T. pakawa |

| Binomial name | |

| Trachymyrmex pakawa Sanchez-Peña, Chacón-Cardosa, Canales-Del Castillo & Reséndez-Pérez, 2017 | |

An inhabitant of the northern Sierra Madre Oriental range, this ground nesting species makes inconspicuous nest entrances.

Identification

Sanchez-Peña et al. (2017) - Similar to Trachymyrmex smithi but antennal scapes clearly longer, resulting in Scape Index values of 93–109; head not as clearly cordate, nor broader than long; color dark reddish brown or rarely light ferruginous red.

Among the Nearctic Trachymyrmex septentrionalis species group, this species is the closest (by geographical distribution) to Neotropical species, including the related Trachymyrmex saussurei.

The main differences between T. pakawa and T. smithi include differences in morphology, geographical distribution, ecology, and habitat preference. Morphologically, the antennal scapes of T. pakawa are distinctly longer that those of T. smithi throughout its range resulting in Scape Index values of 93–109, vs. 84–89 in T. smithi (Rabeling et al. 2007). This is the most obvious differential trait. Also, the head is not as clearly cordate as in T. smithi. The color of workers is dark reddish brown, or rarely light ferruginous red, as opposed to deep dark brown, almost black, in T. smithi. In general, T. pakawa has a more spinulose appearance than T. smithi.

Trachymyrmex pakawa is one of the largest species in size for this genus in North America. Color is almost always dark- brown; only one collection, from La Estanzuela, included rusty workers; but these could have been callow (newly emerged) foragers.

Morphologically T. pakawa is sharply different from the nearly sympatric Mycetomoellerius turrifex (which has subparallel preocular and frontal carinae, shorter anntenal scapes, and is lighter in color) and very clearly larger than T. septentrionalis (Rabeling et al. 2007), the southern distribution limit of which is about 300 km to the north, near San Antonio, Texas.

Unlike Trachymyrmex nogalensis, T. pakawa possesses well-developed, long, frontal carinae that extend to the posterior corner of the head; it thus lacks the short, distinctive antennal depressions (so-called “scrobes” in Rabeling et al. 2007) formed by the frontal and preocular carinae. T. pakawa has shorter antennal scapes and longer propodeal spines than T. nogalensis. It also lacks the proximal narrowing or “waist” of the scape, and the lobe just distal to the narrowing, present in T. nogalensis.

The antennal scape in Trachymyrmex carinatus is considerably longer than in T. pakawa, (SI 117–152 in T. carinatus vs. 93.5–109.5, mean = 103.00 (n=22) in T. pakawa). In T. carinatus, the body is only moderately tuberculate and the color is yellowish brown. T. pakawa also lacks the sharp carinae on the vertex of workers, present in T. carinatus and described by Mackay and Mackay (1997).

In T. pakawa, the propodeal teeth are long, longer than the space separating their bases. In other species of the T. septentrionalis group (i. e. T. carinatus and T. septentrionalis) the propodeal spines are as long or shorter than the distance between their bases.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Sanchez-Peña et al. (2017) - From warm-temperate forest and scrubland habitats at the northern Sierra Madre Oriental range in the Mexican states of Coahuila and Nuevo León: more specifically, in the northern Gran Sierra Plegada range and mountains between the cities of Monterrey and Saltillo. This species has also been collected in the mountains in the municipality of Iturbide, Nuevo Leon, near coordinates 24.721111, -99.896389, about 100 km to the south of Monterrey.

The known species range extends between the opposite edges (west and east) of the Gran Sierra Plegada section of the northern Sierra Madre Oriental mountain range. The more geographically distant populations observed and sampled at the edges of the northern Sierra Madre Oriental mountain range are separated by about 80 km on a straight line. In between these known extreme distribution points, several populations have been detected.

Although it is spread over an area covering a few hundred square kilometers, T. pakawa appears to have a discontinuous distribution in its range, and it is not abundant or common.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 25.704834° to 24.721111°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Mexico (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

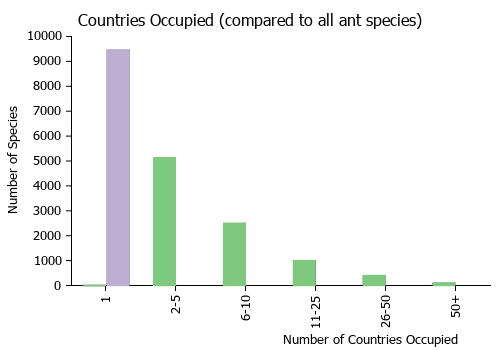

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Habitat

Sanchez-Peña et al. (2017) - This species inhabits very rocky soils, on moderate to very steep slopes, usually between and under large limestone boulders and rocks with a very thin (10–20 cm) cover of lithosol (limestone derived). The sites are rather diverse montane habitats of the southern Nearctic: gallery forests, oak and oak-pine forests, and xerophilous Chihuahuan scrub on slopes (“submontane scrub”).

With the possible exception of the Lomas de Lourdes (Saltillo) population, all these localities are within stands of lechuguilla (Agave lechuguilla ), or within 300 m or less from rocky outcrops where this plant is present. Even the gallery forest at La Estanzuela is within a few hundred meters from lechuguilla stands. This underscores the xerophilous nature of T. pakawa, although it does nest in the more mesic microhabitats (permanent and intermittent springs, creeks, or under and between large rocky outcrops) in a generally arid mountain range. Trachymyrmex pakawa is not found in disturbed habitats

Biology

|

Sanchez-Peña et al. (2017) - Trachymyrmex pakawa has very inconspicuous nest entrances that are rather hard to find. There is no mound, crater, or turret. Trachymyrmex pakawa workers usually forage and arrive at the nest entrance singly; loose trails of four and six ants were observed late in the afternoon on only two occasions. At any time only about four ants can be seen in the general vicinity of the nest. Foragers are very shy and, when disturbed, they retreat inside the nest or feign death and drop to the ground if disturbed at some distance from the nest. This makes them difficult to detect in the field because they are easily scared. Apparently only a very small fraction of the nest´s population leaves the nest at any time to forage, at least during the day. It is not known if nocturnal foraging is significant. Regarding worker numbers in colonies, at least 250 workers emerged from the partially excavated nest by the spring at Lomas de Lourdes. The observed nest chamber was at about 50 cm deep in the spaces between rocks in unusually moist soil. There appeared to be only one queen in this nest.

The reddish detritus accumulations (exhausted fungal substrate) typical of several higher attines (Weber 1972, Sanchez-Peña 2005) are piled at 10–60 cm from the entrance hole and are conspicuous when present. The detritus accumulations of T. pakawa are flat, about 6 cm across. On slopes the detritus does not accumulate.

Trachymyrmex pakawa is a rather cryptic ant. At all locations it is never abundant and foraging workers seem to avoid open flat spaces and clearings, instead walking inconspicuously between vegetation and rocks. At La Estanzuela, Nuevo Leon, workers were noticeably more common at highest elevations (650 m), in the oak-pine forest, at the most mesic conditions observed for this ant. Mature colonies of T. pakawa typically contain 200–300 workers in favorable habitats.

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- pakawa. Trachymyrmex pakawa Sánchez-Peña, Chacón-Cardosa, Canales-Del Castillo & Resendez-Pérez, in Sánchez-Peña, et al. 2017: 79, figs. 2-4 (w.q.) MEXICO (Coahuila, Nuevo León).

- Type-material: holotype worker, paratype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: holotype Mexico: Coahuila, Saltillo, Lomas de Lourdes, 25.365181°N, 100.983217°W, 15.viii.2012, UAN 446, dry oak forest (S.R. Sanchez-Peña); paratypes with same data.

- Type-depositories: USNM (holotype); ASUT, CASC, UAAN, UNAM, USNM (paratypes).

- Status as species: Solomon, Rabeling, et al. 2019: 948.

- Distribution: Mexico.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Head trapezoidal, weakly cordate; HW= 1.13, HL= 1.1 (mm) (holotype), nearly square or slightly rectangular, very slightly broader than long; head widest at midpoint between the eye and the posterior corner, and tapering anteriorly. Posterior margin of head is only moderately concave, slightly notched.

Vertex of head and gaster moderately tuberculate, more markedly spinulose than Trachymyrmex smithi; tubercles thin and resembling spines, base of tubercles not confluent as in T. smithi. Tubercles on preoccipital lobes almost as long as preoccipital spines. Supraocular projections absent. Discal area of mandibles finely striated.

In full-face view, the frontal lobes are small, broadly triangular, usually asymmetrical, with anterior margin longer than posterior.

The margin of the frontal lobes is sub-triangular, smooth, and not crenulated; the base of the frontal lobes lacks projections. Anterior and posterior margin of frontal lobes straight. Base of antennal scapes lacking lobe. Anterior surface of antennal scapes smooth or weakly microtuberculate. Antennal scapes long, surpassing the posterior corner of head by more than twice their maximum diameter.

Frontal and preocular carina ending separately. In full-face view, frontal carina extends almost to posterior corners, but weakening before reaching vertex. Preocular carina well developed, crossing nearly half distance between eye and frontal carina, curving mesad towards, but not reaching, the frontal carina; frontal carina faintly reaching posterior cephalic margin, forming weakly developed, closed antennal depressions (“scrobes”) without apical tubercles.

Tubercles of gaster and mesosoma small, tubercular setae are weakly to strongly recurved; tubercles on sides of mesosoma minuscule and sparse. Pilosity of gaster and femora consists of hairs only, lacking fine pubescence. Texture of body surface rough, sandpaper-like. In T. pakawa the color is dull reddish to (almost always) dark reddish to dark brown, but unlike T. smithi, no blackish specimens have been observed. Dorsal projections of mesosoma are multituberculate swellings, tooth- or spine-like. Two median pronotal projections are present, appearing as ridges or multituberculate swellings. The inferior pronotal corner has a rounded, blunt, weakly developed, projecting tooth. Anterior median promesonotal tubercles short, vertical, tooth-like in frontal or posterior view. The anterior mesonotal projections are microscopically multituberculate or multidentate swellings, especially in Saltillo collections; they are nearly as long as pronotal lateral projections in La Estanzuela (Monterrey) but notably longer than pronotal lateral ones in material from Saltillo. Posterior mesonotal projections present, shaped as a ridge or multituberculate tooth or tumulus. Pilosity of mesopleura consisting of approximately twelve short, pale (not reddish) thin curved hairs, about half as long as hairs on mesosomal projections. Projections on inferior and superior margin of mesopleura absent.

The propodeal teeth are strongly divergent, spine-like, and longer than distance separating their bases; the teeth are longer than any promesonotal projections, and longer than projections of basal face. The petiolar node has one pair of teeth in specimens from La Estanzuela, and two (rather clearly) defined pairs of teeth in specimens from Saltillo. Petiolar node from above is as long as broad. Postpetiole from above is distinctly wider than long; the posterior border of postpetiole is notably excised.

Type Material

Holotype worker: Mexico, Saltillo, Coahuila; Lomas de Lourdes, 25.365181°N, 100.983217°W, 15.viii.2012, dry oak forest, ex ground (S. R. Sanchez-Peña). Collection code: UAN446. Specimen code: USNMENT01125073 (National Museum of Natural History).

Paratypes. Additional specimens (workers) with the same collection information as the holotype deposited at ASU-SIBR, California Academy of Sciences, UAAAN, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico and USNM.

Etymology

From the name of an ancient, vanished Native American tribe that used to live in the same general area of arid northeastern Mexico, where Trachymyrmex pakawa is known to occur.

References

- Sanchez-Peña, S.R., Chacón-Cardosa, M.C., Canales-Del-Castillo, R., Ward, L. & Reséndez-Pérez, D. 2017. A new species of Trachymyrmex (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) fungus-growing ant from the Sierra Madre Oriental of northeastern Mexico. ZooKeys 706, 73–94 (doi:10.3897/zookeys.706.12539).

- Solomon, S.E., Rabeling, C., Sosa-Calvo, J., Lopes, C.T., Rodrigues, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci Jr, M., Mueller, U.G., Schultz, T.R. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939-956 (doi:10.1111/syen.12370).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Sanchez-Pena S. R., M. C. Chacon-Cardosa, R. Canales-del-Castillo, L. Ward, and D. Resendez-Perez. 2017. A new species of Trachymyrmex (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) fungus-growing ant from the Sierra Madre Oriental of northeastern Mexico. ZooKeys 706: 73–94.