Acromyrmex crassispinus

| Acromyrmex crassispinus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Acromyrmex |

| Species: | A. crassispinus |

| Binomial name | |

| Acromyrmex crassispinus (Forel, 1909) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Acromyrmex crassispinus is the most common leaf-cutting ant species in southern Brazil (Rando & Forti, 2005).

Identification

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: -20.8961° to -31.632389°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

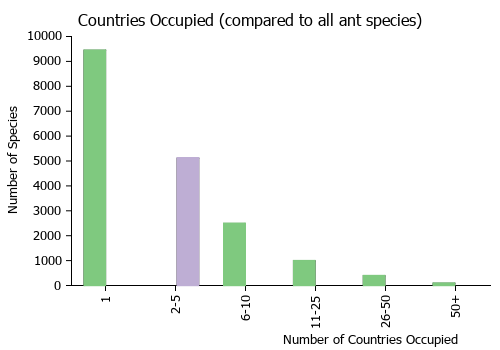

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Nickele and Reis Filho (2015) studied the population dynamics of this species in São Mateus do Sul city (25°58’56,33”S, 50°23’49,26”W, alt. 766 m) state of Parana, Brazil. They worked in recently-planted Pinus taeda plantations (clear cut June-July, 2007 and replanted August, 2007). Initially the plantations contained no colonies of Acromyrmex crassispinus and within a few years the developing canopy created enough shade that none of the incipient colonies initially found, and studied, remained. The initial open nature of the tree plantation was a good area for the initiation of incipient nests, despite the subsequent poor nature of the site over a longer time frame.

The presence of A. crassispinus nests was observed from 15 months after planting (Spring/2008), where there was one nest per hectare, on average. Nest density rose to 26 nests per hectare at 30 months after planting (Summer/2010), then declined through time, Fifty-four months after planting, the forest canopy closed and at 72 months after planting, there was only 0.33 nests per hectare, on average. The few nests observed after 54 months after planting were located near tree gaps in the middle of planting.

In the spring of 2009, winged male or female ants were not observed in the nests sampled. In the spring of 2010, winged ants were observed in 50, 20, 20 and 10% of the nests sampled in September, October, November and December, respectively). Males emerge earlier than females. In several nests, while males were already adult, females were still in the pupal stage. Reproductives only occurred in the largest sized nests sampled. The presence of reproductive ants in sampled colonies only from the spring of 2010 (three years after planting) suggests the first nuptial flight of an A. crassispinus colony also occurs after the third year of the colony foundation.

Barrera et al. (2015) studied the diversity of leaf cutting ants along a forest-edge-agriculture habitat gradient. Their study site, in Chaco Serrano of Central Argentina, had forest remnants of various sizes within an agriculture area with wheat, soy and maize. A. crassispinus was the most common species (42% of the 162 colonies sampled). This species was especially abundant in the forest interior and nest abundance here was positively correlated with the size of the forest remnant (12 sites, from 0.42 ha to > 1,000 ha forest area). Along the forest edge it was slightly less abundant than Acromyrmex lundii and Amoimyrmex striatus. A few colonies of Acromyrmex heyeri and Amoimyrmex silvestrii were also found along the forest edge.

Nickele et al., (2009) found this species prefers to nest in open areas.

Foraging

Nickele et al. (2015) studied this species in Paraná, Brazil, both in the field and lab, to elucidate details of their leaf transport. Some of their findings: In Acromyrmex crassispinus cutting and carrying of fragments were clearly separated activities performed by distinct worker groups differing in body size. Cutters were larger than carriers. In addition, the behavior of foragers of differed significantly according to variation in trail distances. On short trails (1 m), cutters frequently transported the fragments directly to the nest, whereas on long trails (more than 10 m), most cutters transferred the fragments to other workers. Transport chains (fragments found on the trail or directly received from nestmates are transported consecutively by different carriers) happened more frequently when workers harvested plants far from the nest. Transfer was mostly indirect, in other words, fragments were dropped on the ground and collected by outgoing workers that turned back and returned to the nest. Direct fragment transfers between workers were not observed under laboratory conditions. It was observed only on long trails in the field. Lopes et al. (2003) also did not observe direct fragment transfers for this species under laboratory conditions. These results demonstrate that Acromyrmex species display both division of labor between cutters and carriers, and task partitioning during leaf transport, with trail lengths showing marked effects on the likelihood of sequential transport. Furthermore, the results of this study provide support for the hypothesis that the behavioral response of transferring fragments in Acromyrmex species would have been selected for because of its positive effect on the information flow between workers.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a host for the nematode Panagrolaimus sp. (a parasite) (Quevillon, 2018) (multiple encounter modes; indirect transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the phorid fly Myrmosicarius crudelis (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

Castes

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0173794. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ALWC, Alex L. Wild Collection. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- crassispinus. Atta (Acromyrmex) mesonotalis var. crassispina Forel, 1909a: 257 (w.) PARAGUAY.

- Santschi, 1925a: 374 (q.).

- Combination in Acromyrmex: Emery, 1924d: 349.

- Subspecies of mesonotalis: Forel, 1914e: 11; Emery, 1924d: 349.

- Status as species: Santschi, 1925a: 374; Santschi, 1925d: 241; Borgmeier, 1927c: 131; Gonçalves, 1961: 138; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Cherrett & Cherrett, 1989: 50; Bolton, 1995b: 55; Wild, 2007b: 30.

- Senior synonym of atratus: Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- Senior synonym of diabolica: Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- Senior synonym of insularis: Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- Senior synonym of mediocris: Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- Senior synonym of rusticus: Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- Material of the unavailable name rufescens referred here by Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- atratus. Acromyrmex hispidus st. atratus Santschi, 1925a: 376 (w.q.) ARGENTINA (Córdoba), BRAZIL (Rio Grande do Sul).

- Subspecies of hispidus: Borgmeier, 1927c: 132; Santschi, 1929d: 304.

- Junior synonym of crassispinus: Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 54.

- diabolica. Acromyrmex nigrosetosa var. diabolica Santschi, 1922b: 362 (w.) BRAZIL (Santa Catarina).

- Santschi, 1925d: 240 (m.).

- Subspecies of crassispinus: Santschi, 1925a: 375.

- Status as species: Santschi, 1925d: 240; Borgmeier, 1927c: 131.

- Junior synonym of crassispinus: Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- insularis. Acromyrmex aspersus var. insularis Santschi, 1925d: 242 (w.) BRAZIL (São Paulo: Victoria I., San Sebastião Is).

- Subspecies of aspersus: Borgmeier, 1927c: 129.

- Junior synonym of crassispinus: Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- mediocris. Acromyrmex diabolicus var. mediocris Santschi, 1925d: 241 (w.) BRAZIL (Paraná; in text as Oarana).

- Subspecies of diabolicus: Borgmeier, 1927c: 131.

- Junior synonym of crassispinus: Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 56.

- rusticus. Acromyrmex crassispinus st. rusticus Santschi, 1925a: 375 (w.q.) BRAZIL (Santa Catarina).

- Subspecies of crassispinus: Borgmeier, 1927c: 131.

- Junior synonym of crassispinus: Gonçalves, 1961: 139; Kempf, 1972a: 12; Bolton, 1995b: 57.

Description

Karyotype

- 2n = 38 (Brazil) (Fadini & Pompolo, 1996).

- 2n = 38, karyotype = 12M + 20SM + 4ST + 2A (Brazil) (de Castro et al., 2020).

References

- Barrera, C. A., L. M. Buffa, and G. Valladares. 2015. Do leaf-cutting ants benefit from forest fragmentation? Insights from community and species-specific responses in a fragmented dry forest. Insect Conservation and Diversity. 8:456-463. doi:10.1111/icad.12125

- Barros, L.A.C., Aguiar, H.J.A.C., Teixeira, G.C., Souza, D.J., Delabie, J.H.C., Mariano, C.S.F. 2021. Cytogenetic studies on the social parasite Acromyrmex ameliae (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini) and its hosts reveal chromosome fusion in Acromyrmex. Zoologischer Anzeiger 293, 273–281 (doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2021.06.012).

- Cantarelli, E.B., Costa, E.C., Pezzutti, R.V., Zanetti, R., Fleck, M.D. 2019. Damage by Acromyrmex spp. to an initial Pinus taeda L. planting. Floresta e Ambiente 26, e20160060 (doi:10.1590/2179-8087.006016).

- Cardoso, D. C., Cristiano, M. P. 2021. Karyotype diversity, mode, and tempo of the chromosomal evolution of Attina (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini): Is there an upper limit to chromosome number? Insects 1212, 1084 (doi:10.3390/insects12121084).

- Dahan, R.A., Grove, N.K., Bollazzi, M., Gerstner, B.P., Rabeling, C. 2021. Decoupled evolution of mating biology and social structure in Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 76, 7 (doi:10.1007/s00265-021-03113-1).

- de Castro, C.P.M., Cardoso, D.C., Micolino, R., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. Comparative FISH-mapping of TTAGG telomeric sequences to the chromosomes of leafcutter ants (Formicidae, Myrmicinae): is the insect canonical sequence conserved? Comparative Cytogenetics 14(3): 369–385 (doi:10.3897/CompCytogen.v14i3.52726).

- Emery, C. 1924f [1922]. Hymenoptera. Fam. Formicidae. Subfam. Myrmicinae. [concl.]. Genera Insectorum 174C: 207-397 (page 349, Combination in Acromyrmex)

- Fazam, J.C., Shimizu, G.D., Almeida, J.C.de, Pasini, A. 2021. Mortality of leaf-cutting ants with salicylic acid. Semina: Ciências Agrárias 42, 2599–2606 (doi:10.5433/1679-0359.2021v42n4p2599).

- Forel, A. 1909a. Ameisen aus Guatemala usw., Paraguay und Argentinien (Hym.). Dtsch. Entomol. Z. 1909: 239-269 (page 257, worker described)

- Forel, A. 1914e. Quelques fourmis de Colombie. Pp. 9-14 in: Fuhrmann, O., Mayor, E. Voyage d'exploration scientifique en Colombie. Mém. Soc. Neuchâtel. Sci. Nat. 5(2):1-1090. (page 11, subspecies of mesonotalis)

- Gonçalves, C. R. 1961. O genero Acromyrmex no Brasil (Hym. Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 4: 113-180 (page 139, senior synonym of: atratus, diabolica, insularis, mediocris and rusticus, and material of the unavailable name rufescens referred here)

- Moura, M.N., Cardoso, D.C., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. The tight genome size of ants: diversity and evolution under ancestral state reconstruction and base composition. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa135 (doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa135).

- Nickele, M. A. and W. Reis Filho. 2015. Population Dynamics of Acromyrmex crassispinus (Forel) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and Attacks on Pinus taeda Linnaeus (Pinaceae) plantations. Sociobiology. 62:340-346. doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v62i3.422

- Nickele, M. A., W. Reis Filho, and M. R. Pie. 2015. Sequential load transport during foraging in Acromyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) leaf-cutting ants. Myrmecological News. 21:73-82.

- Santschi, F. 1925a. Revision du genre Acromyrmex Mayr. Rev. Suisse Zool. 31: 355-398 (page 374, queen described, raised to species)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Cuezzo, F. 1998. Formicidae. Chapter 42 in Morrone J.J., and S. Coscaron (dirs) Biodiversidad de artropodos argentinos: una perspectiva biotaxonomica Ediciones Sur, La Plata. Pages 452-462.

- Diehl E., C. E. D. Sanhudo, and E. Diehl-Fleig. 2004. Ground dwelling ant fauna of sites with high levels of copper. Braz. J. Biol., 64(1): 33-39.

- Diehl-Fleig E. 2014. Termites and Ants from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Sociobiology (in Press).

- Figueiredo C. J. de, R. R. da Silva, C. de Bortoli Munhae, and M. S. de Castro Morini. 2013. Ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) attracted to underground traps in Atlantic Forest. Biota Neotrop 13(1): 176-182

- Gonçalves C. R. 1961. O genero Acromyrmex no Brasil (Hym. Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 4: 113-180.

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Klingenberg, C. and C.R.F. Brandao. 2005. The type specimens of fungus growing ants, Attini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Myrmicinae) deposited in the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil. Papeis Avulsos de Zoologia 45(4):41-50

- Mayhe Nunes A. J., and E. Diehl-Fleig. 1994. Acromyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) distribution in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Acta Biologica Leopoldensia 16(1): 115-118.

- Mentone T. O., E. A. Diniz, C. B. Munhae, O. C. Bueno, and M. S. C. Morini. 2011. Composition of ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) at litter in areas of semi-deciduous forest and Eucalyptus spp., in Southeastern Brazil. Biota Neotrop. 11(2): http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v11n2/en/abstract?inventory+bn00511022011.

- Munhae C. B., Z. A. F. N. Bueno, M. S. C. Morini, and R. R. Silva. 2009. Composition of the Ant Fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Public Squares in Southern Brazil. Sociobiology 53(2B): 455-472.

- Oliveira Mentone T. de, E. A. Diniz, C. de Bortoli Munhae, O. Correa Bueno and M. S. de Castro Morini. 2012. Composition of ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) at litter in areas of semi-deciduous forest and Eucalyptus spp., in Southeastern Brazil. Biota Neotrop 11(2): 237-246.

- Osorio Rosado J. L, M. G. de Goncalves, W. Drose, E. J. Ely e Silva, R. F. Kruger, and A. Enimar Loeck. 2013. Effect of climatic variables and vine crops on the epigeic ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Campanha region, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. J Insect Conserv 17: 1113-1123.

- Passos L., and P. S. Oliveira. 2002. Ants affect the distribution and performance of Clusia criuva seedlings, a primarily bird-dispersed rainforest tree. Journal of Ecology 90: 517-528.

- Passos, L. and P.S. Oliveira. 2002. Ants Affect the Distribution and Performance of Seedlings of Clusia criuva, a Primarily Bird-Dispersed Rain Forest Tree. Journal of Ecology 90(3):517-528.

- Passos, L. and P.S. Oliveira. 2003. Interactions between ants, fruits and seeds in a restinga forest in south-eastern Brazil. Journal of Tropical Ecology 19(3):261-270.

- Rodrigues, A., M. Bacci, Jr., U.G. Mueller, A. Ortiz and F.C. Pagnocca. 2008. Microfungal Weeds in the Leafcutter Ant Symbiosis. Microbial Ecology 56:604-614

- Rosa da Silva R. 1999. Formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) do oeste de Santa Catarina: historico das coletas e lista atualizada das especies do Estado de Santa Catarina. Biotemas 12(2): 75-100.

- Rosado J. L. O., M. G. de Gonçalves, W. Dröse, E. J. E. e Silva, R. F. Krüger, R. M. Feitosa, and A. E. Loeck. 2012. Epigeic ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in vineyards and grassland areas in the Campanha region, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Check List, Journal of species lists and distribution 8(6): 1184-1189.

- Santos Rando J. S., and L. C. Forti. 2005. Occurrence of ants Acromyrmex Mayr, 1865 in some cities of Brasil. Maringá 27(2): 129-133.

- Santschi F. 1925. Fourmis des provinces argentines de Santa Fe, Catamarca, Santa Cruz, Córdoba et Los Andes. Comunicaciones del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural "Bernardino Rivadavia" 2: 149-168.

- Santschi F. 1925. Nouveaux Formicides brésiliens et autres. Bulletin et Annales de la Société Entomologique de Belgique 65: 221-247.

- Santschi F. 1925. Revision du genre Acromyrmex Mayr. Revue Suisse de Zoologie 31: 355-398.

- Santschi F. 1929. Nouvelles fourmis de la République Argentine et du Brésil. Anales de la Sociedad Cientifica Argentina. 107: 273-316.

- Silva R.R., and C. R. F. Brandao. 2014. Ecosystem-Wide Morphological Structure of Leaf-Litter Ant Communities along a Tropical Latitudinal Gradient. PLoSONE 9(3): e93049. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093049

- Silva T. S. R., and R. M. Feitosa. 2019. Using controlled vocabularies in anatomical terminology: A case study with Strumigenys (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Arthropod Structure and Development 52: 1-26.

- Suguituru S. S., D. R. de Souza, C. de Bortoli Munhae, R. Pacheco, and M. S. de Castro Morini. 2011. Diversidade e riqueza de formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) em remanescentes de Mata Atlântica na Bacia Hidrográfica do Alto Tietê, SP. Biota Neotrop. 13(2): 141-152.

- Vittar, F. 2008. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la Mesopotamia Argentina. INSUGEO Miscelania 17(2):447-466

- Vittar, F., and F. Cuezzo. "Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la provincia de Santa Fe, Argentina." Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina (versión On-line ISSN 1851-7471) 67, no. 1-2 (2008).

- de Souza D. R., S. G. dos Santos, C. de B. Munhae, and M. S. de C. Morini. 2012. Diversity of Epigeal Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Urban Areas of Alto Tietê. Sociobiology 59(3): 703-117.

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Need species key

- Tropical

- South subtropical

- Nematode Associate

- Host of Panagrolaimus sp.

- Phorid fly Associate

- Host of Myrmosicarius crudelis

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Myrmicinae

- Attini

- Acromyrmex

- Acromyrmex crassispinus

- Myrmicinae species

- Attini species

- Acromyrmex species

- Need Body Text