Acromyrmex insinuator

| Acromyrmex insinuator | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Acromyrmex |

| Species: | A. insinuator |

| Binomial name | |

| Acromyrmex insinuator Schultz, Bekkevold & Boomsma, 1998 | |

An inquiline that has been found in colonies of Acromyrmex echinatior and Acromyrmex octospinosus. Despite the ability of queens to integrate themselves into the nests of both of these species, A. insinuator is seemingly only able to successfully rear new reproductives in colonies of A. echinatior.

| At a Glance | • Inquiline |

Identification

Males and females of A. insinuator very closely resemble their hosts, with typically attine dull matte integuments and typically Acromyrmex-like sculpture, tubercles, and setae. Both sexes retain the plesiomorphic attine palpal formula of 4,2 and antennal segment numbers of 11/13 segments in females/males. A worker caste is still produced, but caste representation is limited to minor workers.

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 9.118° to 9.11643°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Panama (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

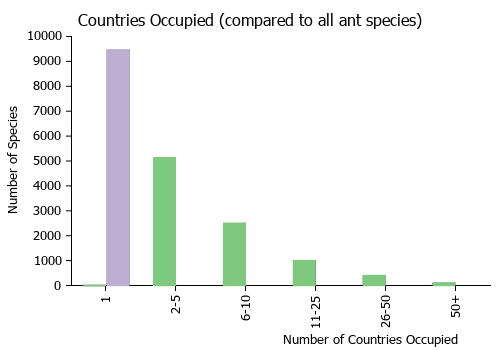

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Schultz et al (1998) - Acromyrmex insinuator is a social parasite of Acromyrmex echinatior. Observations of laboratory nests (Bekkevold and Boomsma, in prep.) suggest that mating flights may occur either slightly prior to or slightly following the mating flights of the host species. If we are correct in assuming that A. insinuator is in the early stages of social parasite evolution, mating flights may be fairly “normal” and it is possible that specimens of both sexes could be collected outside of their symbiotic association, e.g., at light traps. It is not known how inseminated females enter new host nests. It is possible that they may enter established nests; however, the timing of the mating flight does not preclude the alternative possibility that inseminated A. insinuator females may join with A. echinatior queens in pleometrotic nest cofounding.

Acromyrmex insinuator differs remarkably from the only other known attine social parasites, two species that together entirely comprise the genus Pseudoatta. Morphologically, Pseudoatta argentina and P. new species (Delabie et al., 1993) conform to a fairly advanced grade within the “social parasite syndrome” (Hölldobler and Wilson, 1990: 467–469): Males and females are nearly hairless and have remarkably smooth, shining integuments unique for attine ants. In P. argentina, palpal segment number is reduced from the plesiomorphic attine formula of 4, 2 to 3, 2 in both sexes (female: Kusnezov, 1951, 1954; male: TRS, personal observation), and male antennal segment number is reduced from the typical attine 13 to 11. The Bahian Pseudoatta new species retains plesiomorphic palpal formulae and antennal segment numbers in males and females (J. Delabie, pers. comm.). Males of P. argentina are degenerate fliers, mating with their sisters near the host nest entrance (Gallardo, 1929), whereas P. new species apparently conducts normal mating flights (Delabie et al., 1993). Both species are reportedly workerless (Bruch, 1928; Gallardo, 1929; Delabie et al., 1993; J. Delabie, pers. comm.).

The subtle morphological differences between A. insinuator and its host are all interpretable as transitional to a more derived grade of the social parasite syndrome (Hölldobler and Wilson, 1990: 467–469), including: reduction in size (both sexes), pigmentation (frontal triangle in males, ocellar margins in females), sculpture (posteromedian ocellar rugae in females, frontal triangle in males, and anteroventral postpetiole in both sexes), and setation (propodeal dorsum in both sexes). Perhaps significantly, some males have the fourth and fifth funicular segments of the antennae partly fused.

Nehring et al. (2015) - Experiments were performed that included taking queens of the parasite from existing host nests and placing them into a different host nest (both A. echinatior and A. octospinosus host colonies). Parasite queens were initially attacked but many of these queens survived and were eventually accepted in novel host colonies. Aggressive interactions were attenuated when parasite queens were introduced into subcolonies of their original colony or into colonies that already had a parasitic queen present. The cuticular chemical profiles of A. insinuator queens were found to be host colony specific and to contain more nalkanes than host queens. Nalkanes are not generally relevant for nestmate recognition. Overall, the experimental results were suggested to show that A. insinuator queens employ dual, non-exclusive, chemical strategies for invading colonies of their host: chemical insignificance, as evidenced by elevated nalkanes, that allow queens to enter host nests due to the absence of key recognition labels and camouflage, where queens gradually acquire colony specific chemical labels as they become integrated into their host nest.

Castes

Queen

| |

| . | Owned by Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- insinuator. Acromyrmex insinuator Schultz, Bekkevold & Boomsma, 1998: 466, figs. 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16 (w.q.m.) PANAMA.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Based on protein electrophoretic data, the smallest caste of minor workers is present in A. insinuator. However, no obvious morphological differences were detected in a comparison of minor workers from unparasitized nests with those from parasitized nests, including nests in which the alate population was entirely composed of A. insinuator sexuals and in which the complement of A. insinuator minor workers was presumably large. This suggests that workers of A. insinuator may be indistinguishable from workers of the host species, A. echinatior. Obviously, no minor workers of A. insinuator were included in the type series.

Queen

Holotype: HL=1.69; HW=2.14; WL=3.15; SL=1.81; greatest diameter of eye = 0.43.

Possessing the typical attine number of eleven antennal segments and typical palpal formula of 4, 2. Strongly resembling the female caste of the Panamanian form of the host species, Acromyrmex echinatior, to which it is clearly closely related, but on average slightly smaller. Mandible with 8–10 (usually 10) teeth, the apical two larger than the rest. As in both Acromyrmex octospinosus and A. echinatior from the Panamanian nests, the lateral pronotal spines (also called the “superior” pronotal spines) are short and spiniform and the inferior pronotal spines flattened with the tips rounded and blunt. Tubercles on the head are uniformly low and dentiform, agreeing in form and number with those of the host species, except that in both A. echinatior and A. octospinosus the occipital corners are drawn out into a distinct spine; in A. insinuator this tubercle is indistinguishable from the other tubercles on the head. A single strong median ruga extending posteriorly from the central ocellus to the level of the posterior borders of the lateral ocelli; some specimens with an additional one or two weaker rugae. In the Panamanian A. echinatior three to five (typically five) strong rugae are present. There is little or no dark pigmentation of the integument associated with the ocelli; when it is present, such pigmentation is isolated to the immediate areas of individual ocelli and never forms a single, continuous patch. In the Panamanian A. echinatior a single contiguous pigment spot surrounds all three ocelli. Setae are entirely absent from the propodeal dorsum of A. insinuator, whereas they are present in Panamanian A. echinatior females. The propodeal spines are laterally compressed, a condition found in neither A. echinatior or A. octospinosus from any region. In A. insinuator the anteroventral edge of the postpetiole is broadly and evenly concave and without a broad median anteroventral extension; such an extension is consistently present in the Panamanian A. echinatior and variably present in A. octospinosus. Tubercles of the first gastric tergite are of medium height, dentiform and sharp, thus resembling the condition in the host species. Color is yellowish orange.

Male

Allotype: HL = 1.41; HW = 1.70 (eyes included in measurement); WL = 3.04; SL = 1.81; greatest diameter of eye = 0.52.

Possessing the typical attine number of 13 antennal segments (though in 4 individuals from 3 nests funicular segments 4 and 5 are partly fused), and the typical palpal formula of 4, 2. Strongly resembling the male caste of the Panamanian form of the host species, Acromyrmex echinatior, though on average slightly smaller (Table 2; two-tailed t-test on average values: HL: t = 2.584, d.f. = 28, P = 0.0153; HW: t = 4.787, d. f. = 28, P<0.0001; WL: t = 5.046, d.f. = 28, P<0.0001). Mandible with 6–8 variably spaced teeth, the apical two larger than the rest. As in both A. octospinosus and A. echinatior from the Panamanian nests, the lateral pronotal spines are reduced to setigerous tubercles, and the inferior pronotal spines are short, flattened, and triangular. The frontal triangle of A. insinuator males is not delineated by rugae and lacks pigmentation, whereas the frontal triangle in the Panamanian A. echinatior males is darkly pigmented and clearly delimited on all three sides by rugae. The propodeal spines in A. insinuator are extremely laterally compressed and virtually linear in cross section, whereas those of A. echinatior and A. octospinosus males are not compressed and are cylindrical or quadrilateral in cross-section. Setae are absent from the propodeal dorsum in A. insinuator and the postpetiole lacks a broad, convex median anteroventral extension. In Panamanian A. echinatior males both the propodeal setae and the postpetiolar anteroventral median extension are present. Based on a single dissection from each species, there are no obvious differences between A. insinuator and A. echinatior in male genitalic morphology, which was found to conform to the plesiomorphic form for Acromyrmex. Color yellowish-ferrugineous.

Type Material

Paratypes: 28 females, 18 males.

Collection data: Panama, Canal Zone, Gamboa (J.J. Boomsma): holotype, 3 females, 8 males: Nest 22, 20 April 1994; allotype, 7 females, 3 males: Nest 23, 21 April 1994; 8 females, 5 males: Nest 1, 26 April 1993; 4 females, 1 male: Nest 7, 29 April 1993; 6 females, 1 male: Nest 39, 21 January 1996.

Specimen deposition: Holotype, allotype, paratypes: National Museum of Natural History; paratypes: Museum of Comparative Zoology; Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History; Natural History Museum (London); collection of Philip Ward, University of California, Davis; Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil.

References

- Baer, B. 2011. The copulation biology of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 14: 55-68.

- Barros, L.A.C., Aguiar, H.J.A.C., Teixeira, G.C., Souza, D.J., Delabie, J.H.C., Mariano, C.S.F. 2021. Cytogenetic studies on the social parasite Acromyrmex ameliae (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini) and its hosts reveal chromosome fusion in Acromyrmex. Zoologischer Anzeiger 293, 273–281 (doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2021.06.012).

- Buschinger, A. 2009. Social parasitism among ants: a review (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 12: 219-235.

- Cantone S. 2018. Winged Ants, The queen. Dichotomous key to genera of winged female ants in the World. The Wings of Ants: morphological and systematic relationships (self-published).

- Casacci, L.P., Barbero, F., Slipinski, P., Witek, M. 2021. The inquiline ant Myrmica karavajevi uses both chemical and vibroacoustic deception mechanisms to integrate into its host colonies. Biology 10, 654 (doi:10.3390/ biology10070654)..

- de la Mora, A., Sankovitz, M., Purcell, J. 2020. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as host and intruder: recent advances and future directions in the study of exploitative strategies. Myrmecological News 30: 53-71 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_030:053).

- Dijkstra, M.B., Boomsma, J.J. 2003. Gnamptogenys hartmani Wheeler (Ponerinae: Ectatommini): an agro-predator of Trachymyrmex and Sericomyrmex fungus-growing ants. Naturwissenschaften 90, 568–571 (doi:10.1007/s00114-003-0478-4).

- Liberti, J., Sapountzis, P., Hansen, L.H., Sørensen, S.J., Adams, R.M.M., Boomsma, J.J. 2015. Bacterial symbiont sharing in Megalomyrmex social parasites and their fungus-growing ant hosts. Molecular Ecology 24, 3151–3169 (doi:10.1111/MEC.13216).

- Nehring, V., F. R. Dani, S. Turillazzi, J. J. Boomsma, and P. d'Ettorre. 2015. Integration strategies of a leaf-cutting ant social parasite. Animal Behaviour. 108:55-65. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.07.009

- Ramalho, M.de O., Kim, Z., Wang, S., Moreau, C.S. 2021. Wolbachia Across Social Insects: Patterns and Implications. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 114, 206–218 (doi:10.1093/aesa/saaa053).

- Schultz, T. R.; Solomon, S. A. 2002. [Untitled. Cyphomyrmex muelleri Schultz and Solomon, new species.] Pp. 336-337 in: Schultz, T. R.; Solomon, S. A.; Mueller, U. G.; Villesen, P.; Boomsma, J. J.; Adams, R.

- Schultz, T.R., Bekkevold, D. ; Boomsma, J.J. 1998. Acromyrmex insinuator new species; an incipient social parasite of fungus-growing ants. Insectes Soc. 45(4): 457-471 (page 466, figs. 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16 worker, queen, male described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Kooij P. W., B. M. Dentinger, D. A. Donoso, J. Z. Shik, and E. Gaya. 2018. Cryptic diversity in Colombian edible leaf-cutting ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insects 9: 191.

- Sumner, S., D.K. Aanen, J. Delabie and J.J. Boomsma. 2004. The evolution of social parasitism inAcromyrmexleaf-cutting ants: a test of Emerys rule. Insectes Sociaux 51(1):37-42.

- Sumner, S., W.O.H. Hughes and J.J. Boomsma. 2003. Evidence for Differential Selection and Potential Adaptive Evolution in the Worker Caste of an Inquiline Social Parasite. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 54(3):256-263