Camponotus novaeboracensis

| Camponotus novaeboracensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Formicinae |

| Tribe: | Camponotini |

| Genus: | Camponotus |

| Subgenus: | Camponotus |

| Species complex: | herculeanus |

| Species: | C. novaeboracensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Camponotus novaeboracensis (Fitch, 1855) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Camponotus novaeboracensis nests in rotten wood, (Mackay and Mackay, 2002), in and under logs and stumps, in dead branches on the ground and under bark, boards, or even under stones (especially incipient nests) and cow dung (Wheeler and Wheeler, 1963; Hansen and Klotz 2005). New nests can be found in hollow twigs. Colonies are small, with about 3000 workers (Hansen and Klotz 2005). Gibson (1989) discusses the production of soldiers during colony growth, with older colonies having a higher proportion of majors. Brood and sexuals were found in nests in June, August and September. Dealate females were collected in April, June, July and August, a flight was observed in June (21:00 - 22:00). (Mackay, 2019)

Photo Gallery

Identification

The following information is derived from Mackay, New World Carpenter Ants (2019)

Compare with Camponotus chromaiodes, Camponotus herculeanus, Camponotus pennsylvanicus.

The majors, minors and females of C. novaeboracensis have a black head and gaster and a red mesosoma, making them large very attractive ants. The females can be completely black. Erect and suberect setae are sparse on the head, mesosoma, petiole and gaster and absent on the cheeks, malar area, sides of the head, posterior lateral corners and tibiae, except for 2 rows of setae on the flexor surface.

The males are moderately large (total length 8 mm) black ants.

Comparisons

The major of C. novaeboracensis has lateral clypeal angles, which are not well developed. The antennal scapes are without erect and suberect setae (except at the apex) and extend nearly 1 funicular segment past the posterior lateral corners of the head in both the majors and the females. The pubescence on the gaster of all castes of C. novaeboracensis is very fine, with none of the setae overlapping adjacent setae. The punctures on the head are of two sizes, the majority are very fine, and the other scattered punctures are larger in diameter. These characteristics usually separate this species from others of the subgenus Camponotus.

Camponotus novaeboracensis is very similar to Camponotus pennsylvanicus (S Canada, US). They can be separated as the workers and often the females of C. novaeboracensis are bicolored, whereas they are nearly always concolorous black in C. pennsylvanicus. Questionable specimens can be separated as the setae on the gaster of workers and females of C. novaeboracensis are relatively short, with few or no appressed setae overlapping adjacent setae, whereas in C. pennsylvanicus the setae are longer and most overlap adjacent setae. Unfortunately, neither of these characteristics serve to separate the males, and there are no obvious characters which will separate them. Camponotus novaeboracensis is sympatric with C. pennsylvanicus in Iowa with no integration which is strong evidence that they are separate species (Buren, 1944).

Camponotus novaeboracensis can be confused with Camponotus herculeanus (S Canada, US), and the two species are genetically similar (Sämi Schär, et al., 2018). The major workers are usually easy to separate, as the scapes of C. herculeanus do not extend past the posterior lateral corner of the head (they extend well past the corners in C. novaeboracensis). The minor workers of C. novaeboracensis can often be separated as the mesosoma of C. herculeanus is mostly black, or dark red, whereas it is normally red, contrasting with the black head and gaster in C. novaeboracensis. The females of the two species are very difficult to separate. The female of C. herculeanus has a wider head, with the cephalic index ranging from 113 - 114. The cephalic index of C. novaeboracensis ranges from 106 to 108. The dorsum of the mesosoma of the female of C. herculeanus is nearly always black, whereas it is normally partially red in C. novaeboracensis.

It is possible to confuse C. novaeboracensis with Camponotus chromaiodes as they are both mostly dark, with a partially red mesosoma. They can be best separated as the setae on the dorsum of the gaster of C. novaeboracensis are short and similar to the color of the background, whereas they are longer and golden on the gaster of C. chromaiodes, including on the major, minor and female.

Distribution

The following information is derived from Mackay, New World Carpenter Ants (2019)

Camponotus novaeboracensis is found in several habitats including deciduous forest, pine/oaks on sand, beach maple, hardwood forest, mixed hardwood conifer forest and oak-evergreen forest, as well as oak, ash, cottonwoods, aspen, willow woods and grasslands (Wheeler and Wheeler, 1963) in addition to black cherry forests (Yitbarek et al., 2011), grasslands and shrublands (Barber, 2015) and open fields (Oberg, 2012). Buren (1944) concluded it was more boreal than C. pennsylvanicus.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 62.41323333° to 1.311674476°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: Canada, United States (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

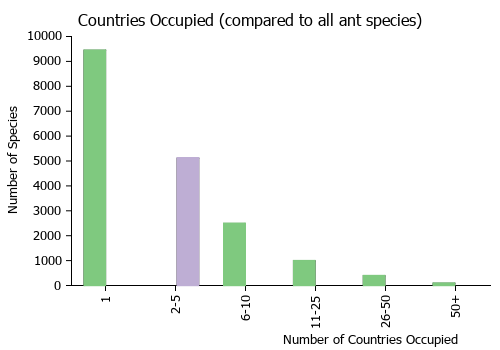

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Biology

The following information is derived from Mackay, New World Carpenter Ants (2019)

Sanders (1972) studied foraging in C. novaeboracensis and found that the start of seasonal activity was temperature dependent and peaked in mid-summer. Workers forage throughout the day and night.

Food sources include honeydew produced by the membracid, Vanduzea arquata (Say), the sap exudate flowing from a wound in the trunk of a common lilac, Syringa vulgaris, and the carcasses of dead insects (Gotwald, 1968). The behavior of the worker ants in exploiting each of these sources is discussed in detail by Gotwald (1968). It is a honeydew feeder (Oberg, 2012), which tends aphids (Jones, 1929), as well as membracids patrolling bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) during the sensitive crozier growth stage. At times these ants remove herbivorous insects from rapidly expanding fronds (Oldenkamp and Douglas, 2011).

Camponotus novaeboracensis is a behaviorally dominant ant (Oberg, 2012) with a strong negative association with the congener Camponotus pennsylvanicus (Thompson and McLachlan, 2007), although it can be a neutrally interacting species found mainly in forest plots (Del Toro et al., 2013).

Camponotus novaeboracensis is the host of the ant cricket Myrmecophilus pergandei (Hebard, 1920), and the principal host for Nemadus triangulum (Coleoptera: Leiodidae) (Peck and Cook, 2007). Reemer (2012) discusses parasitism by the syrphid fly Microdon sp. It is the host of parasites Microdon cothurnatus and M. tristis (Duffield, 1981). The pupae are parasitized by Pseudochalcura gibbosa (Eucharitidae) wasps (Wheeler, 1907; Lachaud, J.-P. and G. Pérez-Lachaud. 2012). Ants carry wasp larvae to the nest and feed them, where the small wasp eats ants (Ellison et al., 2012).

They are the host of the endosymbiotic bacterium Candidatus Blochmannia (Degnan et al., 2004) and the host of Wolbachia bacteria (Wernegreen et al., 2009). They have gram-negative prokaryotic endosymbionts in the follicle cells (Peloquin et al., 2001).

It is an occasional house pest (Mackay and Mackay, 2002; Hansen and Klotz 2005).

Fitzpatrick et al. (2013) used the models MaxEnt and MaxLike to predict the distribution.

It was introduced into Bermuda (Hilburn et al., 1990), but is apparently not established (Wetter and Wetter, 2004).

Additional Notes

The pupae of this medium-sized carpenter ant are often parasitized by small Pseudochalcura gibbosa wasps; the larvae of these wasps are taken back to the nest by the ants as a food source for the developing brood. But the eaten become the eaters, as some of the wasp larvae develop and then devour the ants. (Ellison et al. 2012)

Flight Period

| X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info. Notes: Washington (May).

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

- Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Chaitophorus nigrae (a trophobiont) (Jones, 1927; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Cinara schwarzii (a trophobiont) (Jones, 1927; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Lachnus solitarius (a trophobiont) (Jones, 1927; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a host for the eucharitid wasp Pseudochalcura gibbosa (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (primary host).

- This species is a host for the cricket Myrmecophilus pergandei (a myrmecophile) in United States.

- This species is a host for the Microdon fly Microdon albicomatus (a predator) (Paulson & Akre, 1991; www.diapriid.org).

- This species is a prey for the Microdon fly Microdon cothurnatus (a predator) (Quevillon, 2018).

- This species is a prey for the Microdon fly Microdon tristis (a predator) (Quevillon, 2018).

- This species is a host for the phorid fly Trucidophora camponoti (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

Life History Traits

- Queen number: monogynous (Frumhoff & Ward, 1992)

Castes

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0103349. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by USNM, Washington, DC, USA. |

Male

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0103350. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by USNM, Washington, DC, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- novaeboracensis. Formica novaeboracensis Fitch, 1855: 766 (w.) U.S.A. (New York).

- [Misspelled as noveboracensis by Wheeler, W.M. 1910d: 340, Creighton, 1950a: 369, Mackay, 2019: 277, and many others.]

- Wheeler, W.M. 1910d: 340 (s.w.q.m.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1953e: 182 (l.).

- Combination in Camponotus: Roger, 1863b: 6;

- combination in C. (Camponotus): Emery, 1925b: 72.

- As unavailable (infrasubspecific) name: Wheeler, W.M. 1900c: 47; Wheeler, W.M. 1906b: 23; Wheeler, W.M. 1908f: 625; Wheeler, W.M. 1910d: 340; Wheeler, W.M. 1910g: 571; Wheeler, W.M. 1916m: 601; Wheeler, W.M. 1917a: 557; Wheeler, W.M. 1917c: 27; Wheeler, W.M. 1917i: 466; Cole, 1936a: 39; Wing, 1939: 163; Wesson, L.G. & Wesson, R.G. 1940: 103; Cole, 1942: 388; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 839.

- Junior synonym of herculeanus: Mayr, 1863: 399; Forel, 1874: 96 (in list); Emery & Forel, 1879: 447; Emery & Forel, 1879: 447.

- Junior synonym of pennsylvanicus: Mayr, 1886d: 420; Dalla Torre, 1893: 247; Emery, 1896d: 372 (in list).

- Subspecies of ligniperda: Forel, 1899c: 130.

- Subspecies of herculeanus: Emery, 1925b: 72; Buren, 1944a: 293; Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, E.W. 1944: 250; Buren, 1944a: 293.

- Status as species: Roger, 1863b: 6; Creighton, 1950a: 369; Smith, M.R. 1958c: 142; Smith, M.R. 1967: 366; Francoeur, 1975: 264; Francoeur, 1977b: 207; Yensen, et al. 1977: 184; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1426; Allred, 1982: 456; Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1986g: 60 (in key); DuBois & LaBerge, 1988: 146; Wheeler, G.C., et al. 1994: 305; Bolton, 1995b: 114; Mackay & Mackay, 2002: 298; Coovert, 2005: 167; Hansen & Klotz, 2005: 84; Ellison, et al. 2012: 123; Mackay, 2019: 277 (redescription).

- Senior synonym of pictus: Forel, 1899c: 130; Wheeler, W.M. 1910d: 340; Creighton, 1950a: 369; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 839; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1427; Bolton, 1995b: 114; Mackay, 2019: 278.

- Senior synonym of rubens: Creighton, 1950a: 370; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1427; Bolton, 1995b: 114; Mackay, 2019: 278.

- pictus. Camponotus ligniperdus var. pictus Forel, 1886f: 141.

- [First available use of Camponotus herculeanus r. ligniperdus var. pictus Forel, 1879a: 59 (w.q.m.) U.S.A. (Illinois, Wisconsin), MEXICO; unavailable (infrasubspecific) name.]

- As unavailable (infrasubspecific) name: Emery, 1893i: 674; Emery, 1896d: 372 (in list); Wheeler, W.M. 1905f: 402.

- Subspecies of herculeanus: Mayr, 1886d: 420; Cresson, 1887: 255.

- Subspecies of ligniperda: Dalla Torre, 1893: 240.

- Junior synonym of novaeboracensis: Forel, 1899c: 130; Wheeler, W.M. 1910d: 340; Creighton, 1950a: 369; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 839; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1427; Bolton, 1995b: 117; Mackay, 2019: 278.

- rubens. Camponotus (Camponotus) herculeanus var. rubens Emery, 1925b: 73.

- [First available use of Camponotus herculeanus subsp. ligniperdus var. rubens Wheeler, W.M. 1906a: 41 (w.m.) U.S.A. (Maine, Michigan); unavailable (infrasubspecific) name.]

- As unavailable (infrasubspecific) name: Wheeler, W.M. 1906b: 24; Wheeler, W.M. 1910d: 341; Wheeler, W.M. 1910g: 571; Wing, 1939: 163; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 842; Smith, M.R. 1958c: 161.

- Junior synonym of novaeboracensis: Creighton, 1950a: 370; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1427; Bolton, 1995b: 121; Mackay, 2019: 278.

Type Material

Camponotus herculeanus ligniperda var. rubens: 2 cotype females, 1 cotype male, Main, Bothel, A Edwards (1 q, 1 m MCZC # 21446), Michigan, 1864, C. Clark (1 q MCZC # 21446) [all seen]. Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Major worker measurements (mm): HL 2.08 - 2.92, HW 2.12 - 3.22, SL 1.98 - 2.32, EL 0.48 - 0.61, CL 0.65 - 0.99, CW 0.89 - 1.10, WL 2.54 - 3.62, FFL 1.70 - 2.06, FFW 0.54 - 0.68. Indices: CI 102 - 110, SI 79 - 95, CLI 111 - 137, FFI 32 - 33.

Erect and suberect setae present on clypeus, along frontal carinae and tip of scape, absent on side of head, on cheek, posterior lateral corner of head and scape, few erect and suberect setae on ventral surface of head, scattered on dorsum of mesosoma, petiole and all surfaces of gaster, absent on tibiae, except for double row on flexor surface, especially well-developed near tibial spur; appressed pubescence sparse and scattered on head, dorsum of mesosoma and dorsum of gaster, abundant on tibiae, few setae touch adjacent setae on any surface.

Head with dense, fine punctures and with scattered larger punctures, mesosoma coriaceous, gaster with fine, transverse striolae, with scattered larger punctures which bear decumbent setae.

Head and gaster black, mesosoma and legs red; head occasionally red.

Minor worker measurements (mm): HL 1.18 - 1.64, HW 1.02 - 1.44, SL 1.24 - 1.68, EL 0.36 - 0.40, CL 0.34 - 0.49, CW 0.51 - 0.76, WL 1.66 - 2.24, FFL 0.96 - 1.46, FFW 0.34 - 0.43. Indices: CI 86 - 88, SI 102 - 105, CLI 152 - 156, FFI 29 - 35.

Similar to major worker, except eyes nearly reach sides of head, head oval-shaped, scapes extending nearly ½ length past posterior lateral corner of head, pilosity, sculpture and color as in major worker.

Female measurements (mm): HL 2.70 - 2.86, HW 2.88 - 3.06, SL 2.16 - 2.22, EL 0.63 - 0.73, CL 0.89 - 0.98, CW 1.00 - 1.28, WL 4.26 - 5.02, FFL 2.16 - 2.26, FFW 0.66 - 0.74. Indices: CI 106 - 108, SI 78 - 80, CLI 113 - 131, FFI 31 - 33.

Mandible with 5 teeth; sides of head nearly straight, converging anteriorly, posterior margin convex, posterior lateral corners slightly angulate; eyes reaching to within less than 1 minimum diameter of side of head; scape extending about 1 funicular segment past posterior lateral corner of head; mesosoma massive; petiole narrow in profile, apex sharp.

Erect and suberect setae, and appressed pubescence as in major worker, sculpture as in major worker.

Color as in major worker, except mesosoma, petiole and legs dark red, or entire ant may be black.

Male measurements (mm): HL 1.58 - 1.60, HW 1.46 - 1.52, SL 1.72 - 1.76, EL 0.53 - 0.54, CL 0.43 - 0.44, CW 0.68 - 0.73, WL 3.22 - 3.50, FFL 2.14 - 2.24, FFW 0.41 - 0.51. Indices: CI 92 - 95, SI 108 - 111, CLI 159 - 166, FFI 19 - 23.

Moderate sized, black specimen, similar to most others in the genus, except anterior edge of clypeus concave.

References

- Mackay, W.P. 2019. New World Carpenter Ants of the Hyperdiverse genus Camponotus. Volume 1. Introduction, keys to the subgenera and species complexes and the subgenus Camponotus: 412 pp. Lambert Academic Publishing.

- Buren, W. F. 1944a. A list of Iowa ants. Iowa State Coll. J. Sci. 18: 277-312 (page 293, Variety/subspecies of herculeanus)

- Carroll, T.M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). M.S. thesis, Purdue University.

- Creighton, W. S. 1950a. The ants of North America. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 104: 1-585 (page 369, revived status as species, page 370, senior synonym of rubens)

- Dalla Torre, K. W. von. 1893. Catalogus Hymenopterorum hucusque descriptorum systematicus et synonymicus. Vol. 7. Formicidae (Heterogyna). Leipzig: W. Engelmann, 289 pp. (page 247, junior synonym of pennsylvanicus)

- Ellison A. M., N. J. Gotelli, E. J. Farnsworth, and G. D. Alpert. 2012. A Field Guide to the Ants of New England. Yale University Press. 416 pages.

- Emery, C. 1896j. Saggio di un catalogo sistematico dei generi Camponotus, Polyrhachis e affini. Mem. R. Accad. Sci. Ist. Bologna (5)5:363-382 (page 372, junior synonym of pennsylvanicus)

- Emery, C. 1925e. I Camponotus (Myrmentoma) paleartici del gruppo lateralis. Rend. Sess. R. Accad. Sci. Ist. Bologna Cl. Sci. Fis. (n.s.) 29: 62-72 (page 72, Combination in C. (Camponotus), Variety/subspecies of herculeanus)

- Fitch, A. 1855 [1854]. Report [upon the noxious and other insects of the State of New-York]. Trans. N. Y. State Agric. Soc. 14: 705-880 (page 52, worker described)

- Forel, A. 1899h. Formicidae. [part]. Biol. Cent.-Am. Hym. 3: 105-136 (page 130, revived from synonymy as variety of ligniperdus, senior synonym of pictus)

- Higgins, R. J. and B. S. Lindgren. 2015. Seral changes in ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) assemblages in the sub-boreal forests of British Columbia. Insect Conservation and Diversity. 8:337-347. doi:10.1111/icad.12112

- Ivanov, K. 2019. The ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): an updated checklist. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 70: 65–87 (doi:10.3897@jhr.70.35207).

- Lee, C.-C., Weng, Y.-M., Lai, L.-C., Suarez, A.V., Wu, W.-J., Lin, C.-C., Yang, C.-C.S. 2020. Analysis of recent interception records reveals frequent transport of arboreal ants and potential predictors for ant invasion in Taiwan. Insects 11, 356 (doi:10.3390/INSECTS11060356).

- Mackay, W. P. and E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, NY.

- Paulson, G. S., and R. D. Akre. 1991. Trichopria sp (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) reared from Microdon albicomatus Novak (Diptera: Syrphidae). Canadian Entomologist 123:719.

- Rafiqi, A.M., Rajakumar, A., Abouheif, E. 2020. Origin and elaboration of a major evolutionary transition in individuality. Nature 585, 239–244. (doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2653-6).

- Roger, J. 1863b. Verzeichniss der Formiciden-Gattungen und Arten. Berl. Entomol. Z. 7(B Beilage: 1-65 (page 6, Combination in Camponotus)

- Waters, J.S., Keough, N.W., Burt, J., Eckel, J.D., Hutchinson, T., Ewanchuk, J., Rock, M., Markert, J.A., Axen, H.J., Gregg, D. 2022. Survey of ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in the city of Providence (Rhode Island, United States) and a new northern-most record for Brachyponera chinensis (Emery, 1895). Check List 18(6), 1347–1368 (doi:10.15560/18.6.1347).

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1953e. The ant larvae of the subfamily Formicinae. Part II. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 46: 175-217 (page 182, larva described)

- Wheeler, W. M. 1910g. The North American ants of the genus Camponotus Mayr. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 20: 295-354 (page 340, soldier, worker, queen, male described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Allred D. M. 1982. Ants of Utah. The Great Basin Naturalist 42: 415-511.

- Allred, D.M. 1982. The ants of Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 42:415-511.

- Bare O. S. 1929. A taxonomic study of Nebraska ants, or Formicidae (Hymenoptera). Thesis, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, USA.

- Bestelmeyer B. T., and J. A. Wiens. 2001. Local and regional-scale responses of ant diversity to a semiarid biome transition. Ecography 24: 381-392.

- Blades, D.C.A. and S.A. Marshall. Terrestrial arthropods of Canadian Peatlands: Synopsis of pan trap collections at four southern Ontario peatlands. Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada 169:221-284

- Canadensys Database. Dowloaded on 5th February 2014 at http://www.canadensys.net/

- Carroll T. M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Master's Thesis Purdue university, 385 pages.

- Choate B., and F. A. Drummond. 2012. Ant Diversity and Distribution (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Throughout Maine Lowbush Blueberry Fields in Hancock and Washington Counties. Environ. Entomol. 41(2): 222-232.

- Choate B., and F. A. Drummond. 2013. The influence of insecticides and vegetation in structuring Formica Mound ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Maine lowbush blueberry. Environ. Entomol. 41(2): 222-232.

- Clark A. T., J. J. Rykken, and B. D. Farrell. 2011. The Effects of Biogeography on Ant Diversity and Activity on the Boston Harbor Islands, Massachusetts, U.S.A. PloS One 6(11): 1-13.

- Clark Adam. Personal communication on November 25th 2013.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1942. The ants of Utah. American Midland Naturalist 28: 358-388.

- Cole, A.C. 1936. An annotated list of the ants of Idaho (Hymenoptera; Formicidae). Canadian Entomologist 68(2):34-39

- Coovert G. A. 2005. The Ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ohio Biological Survey, Inc. 15(2): 1-207.

- Coovert, G.A. 2005. The Ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Ohio Biological Survey Bulletin New Series Volume 15(2):1-196

- Del Toro I., K. Towle, D. N. Morrison, and S. L. Pelini. 2013. Community Structure, Ecological and Behavioral Traits of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Massachusetts Open and Forested Habitats. Northeastern Naturalist 20: 1-12.

- Del Toro, I. 2010. PERSONAL COMMUNICATION. MUSEUM RECORDS COLLATED BY ISRAEL DEL TORO

- Downing H., and J. Clark. 2018. Ant biodiversity in the Northern Black Hills, South Dakota (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 91(2): 119-132.

- Drummond F. A., A. M. llison, E. Groden, and G. D. Ouellette. 2012. The ants (Formicidae). In Biodiversity of the Schoodic Peninsula: Results of the Insect and Arachnid Bioblitzes at the Schoodic District of Acadia National Park, Maine. Maine Agricultural and forest experiment station, The University of Maine, Technical Bulletin 206. 217 pages

- Dubois, M.B. and W.E. Laberge. 1988. An Annotated list of the ants of Illionois. pages 133-156 in Advances in Myrmecology, J. Trager

- Ellison A. M. 2012. The Ants of Nantucket: Unexpectedly High Biodiversity in an Anthropogenic Landscape. Northeastern Naturalist 19(1): 43-66.

- Ellison A. M., E. J. Farnsworth, and N. J. Gotelli. 2002. Ant diversity in pitcher-plant bogs of Massachussetts. Northeastern Naturalist 9(3): 267-284.

- Ellison A. M., J. Chen, D. Díaz, C. Kammerer-Burnham, and M. Lau. 2005. Changes in ant community structure and composition associated with hemlock decline in New England. Pages 280-289 in B. Onken and R. Reardon, editors. Proceedings of the 3rd Symposium on Hemlock Woolly Adelgid in the Eastern United States. US Department of Agriculture - US Forest Service - Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, Morgantown, West Virginia.

- Ellison A. M., S. Record, A. Arguello, and N. J. Gotelli. 2007. Rapid Inventory of the Ant Assemblage in a Temperate Hardwood Forest: Species Composition and Assessment of Sampling Methods. Environ. Entomol. 36(4): 766-775.

- Ellison A. M., and E. J. Farnsworth. 2014. Targeted sampling increases knowledge and improves estimates of ant species richness in Rhode Island. Northeastern Naturalist 21(1): NENHC-13NENHC-24.

- Glasier J. R. N., S. E. Nielsen, J. Acorn, and J. Pinzon. 2019. Boreal sand hills are areas of high diversity for Boreal ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Diversity 11, 22; doi:10.3390/d11020022.

- Gotelli, N.J. and A.M. Ellison. 2002. Biogeography at a Regional Scale: Determinants of Ant Species Density in New England Bogs and Forests. Ecology 83(6):1604-1609

- Gregg R. E. 1945 (1944). The ants of the Chicago region. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 37: 447-480

- Gregg R. E. 1946. The ants of northeastern Minnesota. American Midland Naturalist 35: 747-755.

- Gregg, R.T. 1963. The Ants of Colorado.

- Headley A. E. 1943. The ants of Ashtabula County, Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). The Ohio Journal of Science 43(1): 22-31.

- Higgins R. J., and B. S. Lindgren. 2006. The fine scale physical attributes of coarse woody debris and effects of surrounding stand structure on its utilization by ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in British Columbia, Canada. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-93. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station pp. 67-73.

- Hoey-Chamberlain R. V., L. D. Hansen, J. H. Klotz and C. McNeeley. 2010. A survey of the ants of Washington and Surrounding areas in Idaho and Oregon focusing on disturbed sites (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology. 56: 195-207

- Ivanov, K. 2019. The ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): an updated checklist. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 70: 65–87.

- Ivanov K., L. Hightower, S. T. Dash, and J. B. Keiper. 2019. 150 years in the making: first comprehensive list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Virginia, USA. Zootaxa 4554 (2): 532–560.

- Jeanne R. J. 1979. A latitudinal gradient in rates of ant predation. Ecology 60(6): 1211-1224.

- Kannowski P. B. 1956. The ants of Ramsey County, North Dakota. American Midland Naturalist 56(1): 168-185.

- Letendre M., A. Francoeur, R. Beique, and J.-G. Pilon. 1971. Inventaire des fourmis de la Station de Biologie de l'Universite de Montreal, St-Hippolyte, Quebec (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Le Naturaliste Canadien 98(4): 591-606.

- Longino, J.T. 2010. Personal Communication. Longino Collection Database

- Lubertazi, D. Personal Communication. Specimen Data from Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard

- Lynch J. F. 1988. An annotated checklist and key to the species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Chesapeake Bay region. The Maryland Naturalist 31: 61-106

- Mackay W. P., and E. E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 400 pp.

- McClelland L. A. 1978. The Nebraska distribution of the ant genus Camponotus Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Master's Thesis, Department of Biology and the faculty of the Graduate of Nebraska at Omaha, 72 pages.

- McDonald D. L., D. R. Hoffpauir, and J. L. Cook. 2016. Survey yields seven new Texas county records and documents further spread of Red Imported Fire Ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren. Southwestern Entomologist, 41(4): 913-920.

- Menke S. B., E. Gaulke, A. Hamel, and N. Vachter. 2015. The effects of restoration age and prescribed burns on grassland ant community structure. Environmental Entomology http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvv110

- Merle W. W. 1939. An Annotated List of the Ants of Maine (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 50: 161-165

- Newman L. M. and R. J. Wolff. 1990. Ants of a northern Illinois Savanna and degraded savanna woodland. Procedings of the twelfth north american prairie conference. Page 71-74

- Ouellette G. D. and A. Francoeur. 2012. Formicidae [Hymenoptera] diversity from the Lower Kennebec Valley Region of Maine. Journal of the Acadian Entomological Society 8: 48-51

- Ouellette G. D., F. A. Drummond, B. Choate and E. Groden. 2010. Ant diversity and distribution in Acadia National Park, Maine. Environmental Entomology 39: 1447-1556

- Paiero, S.M. and S.A. Marshall. 2006. Bruce Peninsula Species list . Online resource accessed 12 March 2012

- Parson G. L., G Cassis, A. R. Moldenke, J. D. Lattin, N. H. Anderson, J. C. Miller, P. Hammond, T. Schowalter. 1991. Invertebrates of the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, western Cascade Range, Oregon. V: An annotated list of insects and other arthropods. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-290. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 168 p.

- Procter W. 1938. Biological survey of the Mount Desert Region. Part VI. The insect fauna. Philadelphia: Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology, 496 pp.

- Sackett T. E., S. Record, S. Bewick, B. Baiser, N. J. Sanders, and A. M. Ellison. 2011. Response of macroarthropod assemblages to the loss of hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), a foundation species. Ecosphere 2(7):art74. doi:10.1890/ES11-00155.1

- Sharplin, J. 1966. An annotated list of the Formicidae (Hymenoptera) of Central and Southern Alberta. Quaetiones Entomoligcae 2:243-253

- Shik, J., A. Francoeur and C. Buddle. 2005. The effect of human activity on ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) richness at the Mont St. Hilaire Biosphere Reserve, Quebec. Canadian Field-Naturalist 119(1): 38-42.

- Smith F. 1941. A list of the ants of Washington State. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist 17(1): 23-28.

- Sturtevant A. H. 1931. Ants collected on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Psyche (Cambridge) 38: 73-79

- Talbot M. 1976. A list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Edwin S. George Reserve, Livingston County, Michigan. Great Lakes Entomologist 8: 245-246.

- Wheeler G. C., J. N. Wheeler, and P. B. Kannowski. 1994. Checklist of the ants of Michigan (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). The Great Lakes Entomologist 26(4): 297-310

- Wheeler G. C., and E. W. Wheeler. 1944. Ants of North Dakota. North Dakota Historical Quarterly 11:231-271.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1987. A Checklist of the Ants of South Dakota. Prairie Nat. 19(3): 199-208.

- Wheeler W. M. 1900. The habits of Ponera and Stigmatomma. Biological Bulletin (Woods Hole). 2: 43-69.

- Wheeler W. M. 1905. An annotated list of the ants of New Jersey. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 21: 371-403.

- Wheeler W. M. 1905. Ants from the summit of Mount Washington. Psyche (Cambridge) 12: 111-114.

- Wheeler W. M. 1906. Fauna of New England. 7. List of the Formicidae. Occasional Papers of the Boston Society of Natural History 7: 1-24.

- Wheeler W. M. 1906. New ants from New England. Psyche (Cambridge) 13: 38-41.

- Wheeler W. M. 1908. The ants of Casco Bay, Maine, with observations on two races of Formica sanguinea Latreille. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 24: 619-645.

- Wheeler W. M. 1910. The North American ants of the genus Camponotus Mayr. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 20: 295-354.

- Wheeler W. M. 1928. Ants of Nantucket Island, Mass. Psyche (Cambridge) 35: 10-11.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Wyoming. Insecta Mundi 2(3&4):230-239

- Wheeler, G.C., J. Wheeler and P.B. Kannowski. 1994. CHECKLIST OF THE ANTS OF MICHIGAN (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE). Great Lakes Entomologist 26:1:297-310

- Wheeler, G.C., J. Wheeler, T.D. Galloway and G.L. Ayre. 1989. A list of the ants of Manitoba. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Manitoba 45:34-49

- Wing M. W. 1939. An annotated list of the ants of Maine (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News 50:161-165.

- Yitbarek S., J. H. Vandermeer, and D. Allen. 2011. The Combined Effects of Exogenous and Endogenous Variability on the Spatial Distribution of Ant Communities in a Forested Ecosystem (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Environ. Entomol. 40(5): 1067-1073.

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Photo Gallery

- Need species key

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- Tropical

- FlightMonth

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Chaitophorus nigrae

- Host of Cinara schwarzii

- Host of Lachnus solitarius

- Eucharitid wasp Associate

- Host of Pseudochalcura gibbosa

- Cricket Associate

- Host of Myrmecophilus pergandei

- ''Microdon'' fly Associate

- Host of Microdon albicomatus

- Host of Microdon cothurnatus

- Host of Microdon tristis

- Phorid fly Associate

- Host of Trucidophora camponoti

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Formicinae

- Camponotini

- Camponotus

- Camponotus novaeboracensis

- Formicinae species

- Camponotini species

- Camponotus species

- Ssr