Mycetomoellerius iheringi

| Mycetomoellerius iheringi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycetomoellerius |

| Species: | M. iheringi |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycetomoellerius iheringi (Emery, 1888) | |

Entry number 2007 in Goncalves’s notebook says “ninho subterraneo com olheiro fino na areia,” that is, subterranean nest in sand with slim opening.

Identification

A member of the Iheringi species group. Mayhe-Nunes and Brandão (2005) - The exclusive character of M. iheringi is the finely striated discal area of the mandibles; however, Emery (1888) reported that some specimens lack such striation. This species falls within Mycetomoellerius kempfi into the same dichotomy in the identification key. Although both share very similar frontal lobes, M. iheringi first (anterior) pair of mesonotal projections are shorter, whereas the second (posterior) ones are longer (sometimes absent in M. kempfi). Two others striking differences are the lack of flexous pilosity and the shape of lobes of antennal scapes in M. iheringi (see discussion for M. kempfi).

Except by the coloration and size of the katepisternum projection we did not observe any other significant variation in the studied specimens.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: -16.256667° to -31.365°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Brazil (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

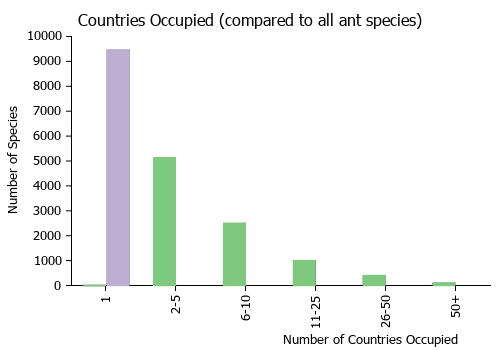

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Castes

Phylogeny

| Mycetomoellerius |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Based on Micolino et al., 2020 (selected species only).

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- iheringi. Atta (Acromyrmex) iheringi Emery, 1888c: 359 (w.q.m.) BRAZIL.

- Combination in Atta (Trachymyrmex): Forel, 1893e: 601.

- Combination in Acromyrmex (Trachymyrmex): Forel, 1914d: 282.

- Combination in Trachymyrmex: Gallardo, 1916b: 242.

- Combination in Mycetomoellerius: Solomon et al., 2019: 948.

- [Name sometimes misspelled as jheringi, for example by Kempf, 1972a: 253.]

- See also: Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão, 2005: 286.

Type Material

Mayhe-Nunes and Brandão (2005) - worker, female and male; Brazil. Rio Grande do Sul: Sao Lourenco.

Two syntype workers labeled “iheringi (type) XXI.V.d.3416 Rio Grande do Sul. Ihering col” in Naturhistorisches Museum, Basel; not examined Dietz personnal communication).

We have found in CECL a pin with one worker labeled as: Rio Gr. do SuI, v. Iheling, 2728, Em. det., Trachymyrmex iheringi Em. det. Borgmeier. Except by the collection number and the identification label, surely written by Borgmeier, the other informations match with Dietz’s annotations taken in the Basel Museum, where he found the syntypes of the species. Kempf (1972) cleared up one information absent in the label of type material: the type locality of the species is Sao Lourenco, at southern Rio Grande do Sul State. Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Mayhe-Nunes and Brandão (2005) - TL 3.5-4 .2; HL 1.05-1.09; HW 0.92-1.00; IFW 0.62-0.69; ScL 0.75-0.85; TrL 1.34- 1.54; HfL 1.15-1.25. Uniformly dark reddish brown to dark brown. Integument fine and shagreened, opaque. Body and appendages clothed with moderately long and oblique to decumbent hairs; mixed with strongly curved short hairs on some parts of occiput, alitrunk, postpetiole and gaster.

Head in full face view as long as broad (CI 100). Mandible fine and completely striate on its dorsal surface, which bears the apical and sub-apical teeth, and 5 regularly developed teeth. Frontal lobe subtriangular, moderately expanded laterad (FLI 65); anterior border concave; posterior border rather straight. Frontal carina diverging caudad, reaching the apex of scrobe. Front and vertex with weak longitudinal rugulae. Posterior third of antennal scrobe clearly delimited by the frontal carina and weakly marked by the extension of the preocular ones. Supraocular projection formed by a group of small tubercles. Occiptal corner rounded in full-face view, surmounted by some stout piligerous tubercles. Occiput slightly notched in the middle. Occipital tooth developed as a stout and tubercle-like projection, rather microtuberculated. Inferior occipital corner emarginated, not forming carina. Eye convex, no more than 12 facets in a row across the greatest diameter. Antennal scape slightly surpassing the occipital margin, when laid back over head as much as possible; basal lobe perpendicularly enlarged, its outer projection bigger than the internal ones, outwards directed when the scape is lodged in the scrobe; anterior surface surmounted by small tubercles and ridges.

Alitrunk. Pronotum with indistinct humeral angle; antero-inferior corner rather angulated; lateral spine long; median projections as a small bifid tubercle. First and second pair of mesonotal projections shorter than pronotal lateral ones, forming a blunt short ridge and teeth-like tubercle, respectively; third pair very small. Mesopleura covered with hairs; superior border of katepisternum vestigially armed with a small and blunt teeth-like projection. Alitrunk weakly constricted dorso-laterally at the shallowly impressed metanotal groove. Basal face of propodeum narrow, laterally delimited by a small dentate ridge; propodeal spines similar to lateral pronotal ones.

Waist and gaster. Petiole shortly pedunculated, the node proper as long as broad, with one pair of small teeth; subpetiolar process vestigial. Poslpetiole slightly broader than long, shallowly excavated above; postero-dorsal border convex; postero-lateral corners without projections. Gaster opaque with minute piligerous tubercles more or less distributed in four irregular longitudinal series on tergum I.

Karyotype

- n = 10, 2n = 20, karyotype = 18M + 2SM (Brazil) (Micolino et al., 2020).

References

- Cardoso, D. C., Cristiano, M. P. 2021. Karyotype diversity, mode, and tempo of the chromosomal evolution of Attina (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini): Is there an upper limit to chromosome number? Insects 1212, 1084 (doi:10.3390/insects12121084).

- Emery, C. 1888c [1887]. Formiche della provincia di Rio Grande do Sûl nel Brasile, raccolte dal dott. Hermann von Ihering. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Ital. 19: 352-366 (page 359, worker, queen, male described)

- Forel, A. 1893h. Note sur les Attini. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 37: 586-607 (page 601, Combination in Atta (Trachymyrmex))

- Forel, A. 1914d. Formicides d'Afrique et d'Amérique nouveaux ou peu connus. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 50: 211-288 (page 282, Combination in Acromyrmex (Trachymyrmex))

- Gallardo, A. 1916c. Notas acerca de la hormiga Trachymyrmex pruinosus Emery. An. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. B. Aires 28: 241-252 (page 242, Combination in Trachymyrmex)

- Mayhé-Nunes, A. J. and Brandão, C. R. F. 2005. Revisionary studies on the attine ant genus Trachymyrmex Forel. Part 2: the Iheringi group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology. 45(2):271-305. (page 286, figs. 25-28 worker described)

- Micolino, R., Cristiano, M.P., Cardoso, D.C. 2020. Karyotype and putative chromosomal inversion suggested by integration of cytogenetic and molecular data of the fungus-farming ant Mycetomoellerius iheringi Emery, 1888. Comparative Cytogenetics 14(2): 197–210 (doi:10.3897/CompCytogen.v14i2.49846).

- Moura, M.N., Cardoso, D.C., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. The tight genome size of ants: diversity and evolution under ancestral state reconstruction and base composition. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa135 (doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa135).

- Solomon, S.E., Rabeling, C., Sosa-Calvo, J., Lopes, C.T., Rodrigues, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci Jr, M., Mueller, U.G., Schultz, T.R. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939-956 (doi:10.1111/syen.12370).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Clemes Cardoso D., and J. H. Schoereder. 2014. Biotic and abiotic factors shaping ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) assemblages in Brazilian coastal sand dunes: the case of restinga in Santa Catarina. Florida Entomologist 97(4): 1443-1450.

- Clemes Cardoso D., and M. Passos Cristiano. 2010. Myrmecofauna of the Southern Catarinense Restinga sandy coastal plain: new records of species occurrence for the state of Santa Catarina and Brazil. Sociobiology 55(1b): 229-239.

- Correia Golias H., J. Lopes, J. H. C. Delabie, and F. de Azevedo. 2018. Diversity of ants in citrus orchards and in a forest fragment in Southern Brazil. EntomoBrasilis doi:10.12741/ebrasilis.v11i1.703

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Rosa da Silva R. 1999. Formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) do oeste de Santa Catarina: historico das coletas e lista atualizada das especies do Estado de Santa Catarina. Biotemas 12(2): 75-100.

- Santos-Junior L. C., J. M. Saraiva, R. Silvestre, and W. F. Antonialli-Junior. 2014. Evaluation of Insects that Exploit Temporary Protein Resources Emphasizing the Action of Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in a Neotropical Semi-deciduous Forest. Sociobiology 61(1): 43-51

- Silva F. H. O., J. H. C. Delabie, G. B. dos Santos, E. Meurer, and M. I. Marques. 2013. Mini-Winkler Extractor and Pitfall Trap as Complementary Methods to Sample Formicidae. Neotrop Entomol 42: 351358.

- Ulyssea M. A., C. E. Cereto, F. B. Rosumek, R. R. Silva, and B. C. Lopes. 2011. Updated list of ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) recorded in Santa Catarina State, southern Brazil, with a discussion of research advances and priorities. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 55(4): 603–611.

- Ulyssea M.A., C. E. Cereto, F. B. Rosumek, R. R. Silva, and B. C. Lopes. 2011. Updated list of ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) recorded in Santa Catarina State, southern Brazil, with a discussion of research advances and priorities. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 55(4): 603-611.

- Veiga-Ferreira S., G. Orsolon-Souza, and A. J. Mayhé-Nunes. 2010. Hymenoptera, Formicidae Latreille, 1809: new records for Atlantic Forest in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Check List 6(3): 442-444.