Mycetomoellerius isthmicus

| Mycetomoellerius isthmicus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycetomoellerius |

| Species: | M. isthmicus |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycetomoellerius isthmicus (Santschi, 1931) | |

Identification

A member of the Jamaicensis species group. Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2007) - Distinguished from all other species of the jamaicensis group by the completely rounded, not dentate nor angulate antero-inferior corner of pronotum, and by the lateral pronotal spines notably smaller and more slender than the mesonotal anterior projections. Other species of the group present lateral pronotal spines longer than mesonotal projections (Mycetomoellerius ixyodus) or of nearly the same length (Mycetomoellerius atlanticus, Mycetomoellerius haytianus, Mycetomoellerius jamaicensis and Mycetomoellerius zeteki).

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 12.9599821° to -2.691°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Costa Rica, Ecuador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

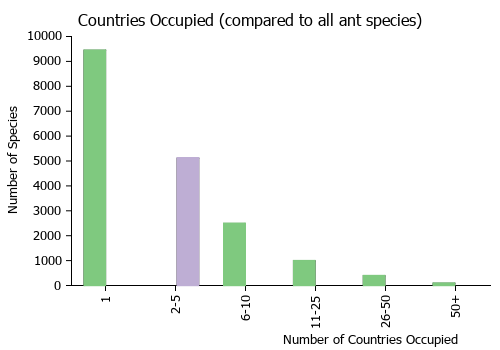

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2007) - A nest observed by Neal Weber (1941:122) had an entrance surrounded by a crater or an erect friable turret. Weber recorded the migration of a colony from the old to a new nest 37cm away, with the workers carrying the nest material piece by piece: fungus garden, insect feces, and mycelium covered larvae. According to him “the history of this migration may be reconstructed as follows: This colony of ants probably nested successfully during the preceding dry season, and perhaps for a long period, in a slight depression on this steep clay slope. During the seven-day period, June 14–20 inclusive, 8.4 inches of rain fell and this depression became water-soaked, inundating the nest or at least soaking the walls of the chamber and wetting the garden. June 21 was a rainless day and the ants started to move the fungus garden and brood to a higher, less water-soaked situation. When I found the nest on June 22 the moving was well underway. By the morning of June 24 the entire nest had been moved. Three days were thus probably consumed in moving. Assuming for rough purposes of calculation that the ants worked steadily the entire time and that 2.2 trips per minute represented an average number, the total number of trips in the 72 hours would be of the order of magnitude of 10,000.”

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- isthmicus. Trachymyrmex isthmicus Santschi, 1931c: 280, figs. 13-15 (w.) PANAMA. Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão, 2007: 10 (q.).

- Combination in Mycetomoellerius: Solomon et al., 2019: 948.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2007) - (n = 4). TL 4.2 (4.0–4.6); DHL 1.22 (1.14–1.29); HW 1.28 (1.25–1.32); IFW 0.66 (0.62–0.68); ScL 1.00 (0.94–1.08); HWL 0.67 (0.60–0.74); MeL 1.56 (1.49–1.68); PL 0.36 (0.32–0.38); PPL 0.45 (0.43–0.49); GL 1.17 (1.08–1.29); HfL 1.64 (1.48–1.78).

Reddish-brown to yellowish-brown; cheeks, frons, and furrow on vertex slightly darker. Integument finely and indistinctly shagreened, opaque. Pilosity: not very abundant bristly hairs with variable length; most of the longest hairs strongly recurved; tergum I of gaster hairs mostly uniform; tarsi with straight and oblique hairs. Fine pubescence confined to antennal funiculi, flexor face of tibiae and tarsi.

Head in full face view (Fig. 9) a little longer than broad to about as long as broad (DCI average 93; 86–97). Outer border of mandible sinuous; masticatory margin with two apical and seven uniform smaller teeth. Clypeus median apron without projections. Frontal area impressed. Frontal lobe semicircular, moderately expanded (FLI average 59; 56–61), with crenate free border; the antero-lateral border with one prominent denticle. Frontal carina moderately diverging caudad, reaching the antennal scrobe posterior end in a small tooth at the vertexal margin; preocular carinae briefly interrupted or fading out just above the supraocular projections, becoming again more distinct further behind, reaching the projected apical multispinose tuberosity, a little longer and stouter than frontal carinae projections. Occipital tooth as strong as preocular carina projection, but truncate and shorter. Supraocular projection well developed, tuberculiform. Inferior corner of vertex, in side view, with a low truncate tooth, similar in size to the vertexal projections. Eye convex, faintly surpassing the lateral border of head, with 12 facets in a row across the greatest diameter. Antennal scape when lodged in the scrobe, projecting beyond the scrobe tip by a distance near one forth of its length; gradually but very little thickened towards apex, without sharp, piligerous tubercles.

Mesosoma (Figs. 10–11). Pronotal dorsum marginate in front and on sides; antero-inferior corner bluntly rounded, without a projecting tooth; inferior margin weakly crenulate; paired median pronotal teeth widely separated from each other, not arising from a common tubercular base, their tips not conspicuously projecting above the tips of the stronger lateral pronotal spines, which point upwards. Anterior pair of mesonotal spines, stouter and higher than pronotal projections; the spine-like second and third pair gradually smaller. Anterior margin of katepisternum smooth, without a projecting tooth. Metanotal constriction impressed. Basal face of propodeum laterally margined by a row of 2–3 denticles on each side; propodeal spines shorter and slender than lateral spines of pronotum, pointing obliquely upwards and laterad, as long as the distance between their inner bases. Hind femora a little longer than mesosoma length.

Waist and gaster (Figs. 11, 12). Dorsum of petiolar node with two pairs of minute denticles, the sides parallel in dorsal view, with one minute spine near the posterior border, and spiracles projected as small tubercles; sternum without sagital keel. Postpetiole trapezoidal in dorsal view, two times broader behind than in front, and shallowly impressed dorsally, with straight postero-dorsal border. Gaster, when seen from above, rather trapezoidal than suboval, posteriorly subtruncate. Tergum I with the flattened yet scarcely excavate lateral faces separated from the dorsal face by a sharp serrate keel; anterior two thirds of dorsum with three longitudinal furrows separated by a pair of median keels consisting of serially arranged and loosely connected piligerous tubercles. Sternum I without an anterior sagital keel or prominent tubercles.

Queen

Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2007) - (Figs. 13, 14): TL 5.3; DHL 1.46; HW 1.28; IFW 0.80; ScL 0.86; HWL 0.82; MeL 1.86; PL 0.51; PPL 0.43; GL 1.63; HfL 1.72. Resembling the worker with the usual caste differences. The median anterior ocellus partially concealed above by a down curved ridge, and the two lateral ones fully hidden by the longitudinal carinae of vertex. Pronotum with a pair of small and acute scapular spines on each side, directed out and obliquely upwards, but lacking inferior ones. Mesoscutum surmounted by conspicuous tubercles, but without notable dorsal projections, superficially impressed on posterior region, with the anterior margin straight in the middle, in dorsal view. Shallowly impressed parapses delimited by the inconspicuous parapsidial furrows; dorsum of mesothoracic paraptera almost vertical in relation to the scutellum dorsum in side view, with a narrow median portion when seen from above; scutellum ending in a pair of small stout and acute spines, directed backwards, with the sides converging obliquely inwards; metathoracic paraptera concealed by the scutellum in dorsal view; propodeal spiracle orifice visible. Two moderately strong and acute spines on propodeum, little longer than pronotal ones. Petiolar dorsum with two pairs of minute teeth near the anterior and posterior margins. First gastric tergite with a longitudinal ridge on each side; disk with two longitudinal series of small piligerous tubercles, absent in the middle of the segment. Wings unknown.

References

- Adams, R.M.M., Jones, T.H., Jeter, A.W., De Fine Licht, H.H., Schultz, T.R., Nash, D.R. 2012. A comparative study of exocrine gland chemistry in Trachymyrmex and Sericomyrmex fungus-growing ants. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 40:91–97 (doi:10.1016/j.bse.2011.10.011).

- Mayhé-Nunes, A.J., Brandão, C.R.F. 2007. Revisionary studies on the attine ant genus Trachymyrmex Forel. Part 3: The Jamaicensis group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa. 1444:1-21 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1444.1.1).

- Santschi, F. 1931d. Fourmis de Cuba et de Panama. Rev. Entomol. (Rio J.) 1:265-282. (page 280, figs. 13-15 worker described)

- Solomon, S.E., Rabeling, C., Sosa-Calvo, J., Lopes, C.T., Rodrigues, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci Jr, M., Mueller, U.G., Schultz, T.R. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939-956 (doi:10.1111/syen.12370).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Basset Y., L. Cizek, P. Cuenoud, R. K. Didham, F. Guilhaumon, O. Missa, V. Novotny, F. Odegaards, T. Roslin, J. Schmidl et al. 2012. Arthropod diversity in a tropical forest. Science 338(6113): 1481-1484.

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- INBio Collection (via Gbif)

- Longino J. T. 2013. Ants of Honduras. Consulted on 18 Jan 2013. https://sites.google.com/site/longinollama/reports/ants-of-honduras

- Longino J. T. 2013. Ants of Nicargua. Consulted on 18 Jan 2013. https://sites.google.com/site/longinollama/reports/ants-of-nicaragua

- Longino J. T. L., and M. G. Branstetter. 2018. The truncated bell: an enigmatic but pervasive elevational diversity pattern in Middle American ants. Ecography 41: 1-12.

- Longino J. T., and R. K. Colwell. 2011. Density compensation, species composition, and richness of ants on a neotropical elevational gradient. Ecosphere 2(3): 16pp.

- Longino J. et al. ADMAC project. Accessed on March 24th 2017 at https://sites.google.com/site/admacsite/

- Mayhe-Nunes A. J., and C. R. F. Brandao. 2007. Revisionary studies on the attine ant genus Trachymyrmex Forel. Part 3: The Jamaicensis group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 1444: 1-21.

- Salazar F., F. Reyes-Bueno, D. Sanmartin, and D. A. Donoso. 2015. Mapping continental Ecuadorian ant species. Sociobiology 62(2): 132-162.

- Santschi F. 1931. Fourmis de Cuba et de Panama. Revista de Entomologia (Rio de Janeiro). 1: 265-282.

- Weber N. A. 1941. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part VII. The Barro Colorado Island, Canal Zone, species. Rev. Entomol. (Rio J.) 12: 93-130.