Mycetophylax strigatus

| Mycetophylax strigatus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycetophylax |

| Species: | M. strigatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycetophylax strigatus (Mayr, 1887) | |

A nest of this species was discovered under the bark of a decaying tree. Ramos-Lacau et al. (2015) found this species co-occurring with Mycetophylax lectus and Cyphomyrmex rimosus in savanna-forest in Southeast Brazil. Colonies were found nesting in the ground. Each nest had a single, simple circular nest-entrance. These averaged a few mm in diameter and did not have any well formed nest mound.

Identification

See the description section below.

Distribution

Southeastern Brazil, from Rio Grande do Sul to Rio de Janeiro States.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 8.451524° to -64.3°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Brazil (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

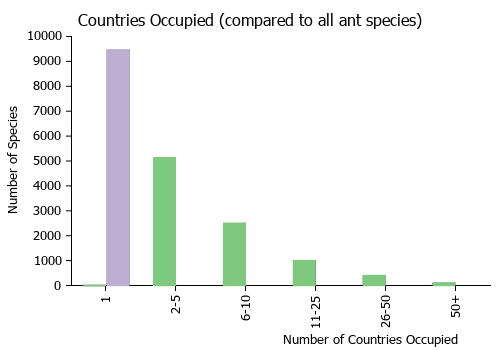

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Kempf (1964) - According to Moeller (1941) this species resembles Mycetophylax auritus as regards the nest side and shape, and the cataleptic behavior of workers upon being disturbed. The fungus garden, however, is of a different aspect, consisting in an irregular agglomerate of small pellets of substrate, loosely heaped one upon another, as in Apterostigma wasmanni (=Apterostigma auriculatum) For. The mycelium shows the bromatia or gongylidia better differentiated than in that of auritus (cf. Moeller's figures 25 and 26). Yet auritus workers in artificial nests freely fed on strigatus fungus and viceversa. The sporophore of the fungus is not known, but seems to be a basidiomycete.

Luederwaldt (1926) discovered a nest under the bark of a decaying tree. The cavity was rounded-elongate, the fungus mass dirty yellowish and irregular in aspect. The colony consisted of approximately 30 workers.

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- strigatus. Cyphomyrmex strigatus Mayr, 1887: 558 (w.) BRAZIL.

- Forel, 1893e: 606 (q.m.); Wheeler, G.C. 1949: 669 (l.).

- Combination in Mycetophylax: Sosa-Calvo et al., 2017: 9.

- See also: Kempf, 1964d: 14.

Description

Worker

Kempf (1964) - Total length 2.9-3.7 mm; head length 0.75-0.89 mm; head width 0.67-0.80 mm; thorax length 0.91-1.17 mm; hind femur length 0.72-0.98 mm. Yellowish brown to dark ferruginous. Integument, including antennal scrobe, indistinctly granulate and opaque. Differs from auritus as follows 1. Smaller in size. Body more compact. Hind femur distinctly shorter than thorax length. 2. Auriculate occipital lobes (fig 6, 44) much less protruding, usually shorter than their maximum diameter. Supraocular tooth blunt and obtuse, lacking a distinct ridge between its base and the inferior occipital angle. Funicular segments 2-8 not longer than broad. 3. Lateral pronotal tubercles blunt and stout. Mesonotal armature (fig 18) relatively low, consisting of blunt tubercles. Longitudinal ridges on basal face of epinotum blunt, without a prominent tooth on posterior corner. Femora feebly marginate on flexor face. Hind femora gently and gradually thickening from base to basal third, where they form an obtuse, at most weakly carinate, angle on flexor face. 4. Petiolar node subquadrate, occasionally somewhat transverse, its anterior corners in dorsal view rounded; longitudinal crests on dorsum only vestigial. Postpetiole with anterior face moderately raised in vertical direction, anterior dorsal tubercles feeble, sides convex, somewhat constricted to slightly diverging behind: in dorsal view little to somewhat transverse. 5. Appressed hairs on frontal lobes, borders of frontal carinae, frontal and vertical ridges, thoracic tubercles, pedicelar tubercles and ridges, gaster, scapes and legs conspicuous and scale-like.

Queen

Kempf (1964) - Total length 4.0-4.3 mm; head length 0.93-0.96 mm; head width 0.83-0.91 mm; thorax length 1.23-1.36 mm; hind femur length 0.91-1.07 mm. Characters as given for the worker, with the same differences from auritus. Note the following: Lateral pronotal tubercles blunt and stout. Scutum and scutellum with shallower depressions and very low and blunt tuberosities. Epinotal tooth tubercular, small to vestigial. Scale-like hairs especially conspicuous on scutum and scutellum.

Type Material

Kempf (1964) - Worker, in the Mayr collection at the "Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien". Not seen.

References

- Forel, A. 1893h. Note sur les Attini. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 37: 586-607 (page 606, queen, male described)

- Franco, W., Ladino, N., Delabie, J.H.C., Dejean, A., Orivel, J., Fichaux, M., Groc, S., Leponce, M., Feitosa, R.M. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674, 509–543 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4674.5.2).

- Kempf, W. W. 1964d. A revision of the Neotropical fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex Mayr. Part I: Group of strigatus Mayr (Hym., Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 7: 1-44 (page 14, see also)

- Ladino, N., Feitosa, R.M. 2022. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Parque Estadual São Camilo, an isolated Atlantic Forest remnant in western Paraná, Brazil. ZOOLOGIA 39: e22001 (doi:10.1590/S1984-4689.v39.e22001).

- Luederwaldt, H. 1926. Observações biologicas sobre formigas brasileiras especialmente do estado de São Paulo. Rev. Mus. Paul. 14:185-303.

- Mayr, G. 1887. Südamerikanische Formiciden. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 37: 511-632 (page 558, worker described)

- Moeller, A. 1941. As hortas de fungo de algumas formigas sulamericanas. Rev. Entomol. (Rio de Janeiro). 1 (Supplemento):1-120.

- Ramos-Lacau, L. S., P. S. D. Silva, J. H. C. Delabie, S. Lacau, and O. C. Bueno. 2015. Nest Biology and Demography of the Fungus-Growing Ant Cyphomyrmex lectus Forel (Myrmicinae: Attini) at a Disturbed Area Located in Rio Claro-SP, Brazil. Sociobiology. 62:462-466. doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v62i3.709

- Sosa-Calvo, J., JesÏovnik, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci, M. Jr., Schultz, T.R. 2017. Rediscovery of the enigmatic fungus-farming ant "Mycetosoritis" asper Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Implications for taxonomy, phylogeny, and the evolution of agriculture in ants. PLoS ONE 12: e0176498 (DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0176498).

- Wheeler, G. C. 1949 [1948]. The larvae of the fungus-growing ants. Am. Midl. Nat. 40: 664-689 (page 669, larva described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Fernandes I., and J. de Souza. 2018. Dataset of long-term monitoring of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the influence areas of a hydroelectric power plant on the Madeira River in the Amazon Basin. Biodiversity Data Journal 6: e24375.

- Franco W., N. Ladino, J. H. C. Delabie, A. Dejean, J. Orivel, M. Fichaux, S. Groc, M. Leponce, and R. M. Feitosa. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674(5): 509-543.

- Kempf W. W. 1964. A revision of the Neotropical fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex Mayr. Part I: Group of strigatus Mayr (Hym., Formicidae). Studia Entomologica 7: 1-44.

- Wheeler G. C. 1949. The larvae of the fungus-growing ants. Am. Midl. Nat. 40: 664-689.