Neivamyrmex opacithorax

| Neivamyrmex opacithorax | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Dorylinae |

| Genus: | Neivamyrmex |

| Species: | N. opacithorax |

| Binomial name | |

| Neivamyrmex opacithorax (Emery, 1894) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Although Neivamyrmex opacithorax is a widespread species it is not as commonly encountered as other members of the N. nigrescens group. It is presumably a raider on other ant species.

Photo Gallery

Identification

Workers have a single eye facet and a short, thick scape. Among Neivamyrmex species, opacithorax workers differs from their congeners by having a mandible with a distinct tooth or sharp angle at the juncture with the masticatory margin and a relatively shiny head.

Smith (1942) - The major worker is most likely to be confused with that of Neivamyrmex nigrescens, which it resembles in structure, especially in the shape of the petiole and postpetiole. From nigrescens it can be distinguished, however, by the nature of the sculpturing and the color of body. The head, thorax, petiole, and postpetiole of nigrescens are opaque, whereas in opacithorax this is true only of the thorax and petiole. The worker of opacithorax is generally of a lighter color; has the eye less distinct; a feebler pronotal carina; a straight instead of a convex margin on the superior border of the mandible between the basal tooth and the masticatory border; and the posterior corners of the head not so noticeably curved outward. There is considerable variation among different individuals in sculpture, pilosity, color, and amount of development of the pronotal carina. Some specimens have such feeble sculpturing that the head and postpetiole are strikingly smooth and shining, whereas other specimens have these regions more heavily sculptured, tending to be subopaque. Although the meso- and metapleura are usually opaque in most individuals, they are somewhat smooth and shining in others. The variation in length of pilosity is often due to wear, as is evidenced by the truncate tips of the hairs. The color may range from a light yellowish brown to a reddish brown, the reddish brown, however, not attaining such a dark shade as in nigrescens or the infuscated effect of some individuals of the latter species. The pronotal carina, although usually distinct, is sometimes almost obsolete.

Queen The female very closely resembles that of nigrescens and on superficial examination might easily be mistaken for the latter. From nigrescens it may be distinguished by the lack of the very prominent tuberculate or angulate posterior corners of the head; the smaller and more indistinct eyes; the less marginated prothorax; the somewhat shining head, which is distinctly less heavily sculptured than the thorax; the shorter pilosity; and the fainter longitudinal median groove on the mesonotum. Wheeler and Long (1901) furnish illustrations of the lateral and dorsal aspect of the female of opacithorax and also give a very brief but accurate description of the ant. Their description and figures were based on the specimen collected at Belmont, Gaston County, N.C., by P. J. Schmitt. This was the first female of Neivamyrmex to have been recognized and described in the United States. A female in the collection of the United States National Museum, bearing only the label "Texas," and which I refer to opacithorax, differs from my description in its smaller size, the almost straight anterior border of the clypeus, the lack of distinct sutures on the thorax, and its much deeper color.

Male The male of opacithorax can be distinguished by the following characters: Small eyes and ocelli; wide space between inner border of eye and lateral ocellus; weak ridge above antennal socket; somewhat slender, subfiliform funiculus; shining head and thorax; and bicolored body. Males from different localities vary in shape of mandibles, color, sculpturing, and pilosity. The mandibles of some individuals are more slender than those of others. The apical slope of the mandible may also vary in length. The sculpturing on the head and thorax of some specimens is more pronounced than in others, thus imparting to these regions a dun cast, which, however, never entirely robs them of a somewhat slightly shining appearance. The color of the body may be dark in some specimens and light in others. The pilosity may range from a light yellowish or almost grayish to a deep golden yellow. The color of the gaster, although it may vary slightly, is always a light brown or reddish brown; whereas the gaster of nigrescens, though sometimes a deep blackish brown, is usually black. The male is most likely to be mistaken for that of nigrescens, from which it can be distinguished by its more slender, subfiliform funiculus; feebly developed ridge above antennal socket; more shining body, especially that of the head and thorax; bicolored body; smaller size; and more slender form. From the male of carolinense it can be distinguished by its larger size; more robust mandibles; larger eyes and ocelli; and less coarse body sculpture, especially that of the dorsum of the thorax and gaster.

Identification Keys including this Taxon

Key to the Neivamyrmex species of the United States

Distribution

United States: Virginia and Tennessee, south to Florida, west to California; Mexico (Baja California, Jalisco); Guatemala; Costa Rica.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 39.296463° to 15.03333333°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States (type locality).

Neotropical Region: Mexico.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

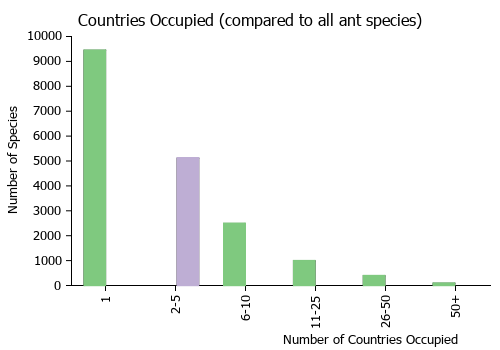

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Biology

Colonies of Neivamyrmex opacithorax likely contain many tens of thousands of individuals. Like other army ants they do not live in a permanent nest but instead form temporary bivouacs. The colony coalesces in the same location, in the evening after a day of raiding, for a number of weeks. The bivouac site is eventual moved to a new location and daytime raids then occur from this new location. This species typically raids below ground but is occasionally seen using an above ground trail.

The following is based on Rettenmeyer (1963), with the references cited here detailed in the original publication.

Neivamyrmex opacithorax has a range approximately equivalent to that of Neivamyrmex nigrescens in the United States, and in addition the former species extends southward to Costa Rica. Both species are found throughout most of the southern states from California to North Carolina and extend farther north in the plains states, Kansas, Nebraska, and Iowa (M. R. Smith, 1942: 558; Borgmeier, 1955: 504). There are a number of seemingly contradictory statements in the literature regarding the relative abundance of these two species. Cole (1953b: 84) reported that opacithorax was much more common in New Mexico than nigrescens. In the Gulf States, M. R. Smith (1942: 560) reported that opacithorax is "never so abundant as" nigrescens. Schneirla (1958a: 221) reported that in Arizona opacithorax is "perhaps as common" as nigrescens, but he also stated, "more than 12 colonies of Neivamyrmex nigrescens and 6 colonies of opacithorax were found . . ." ( p. 241 ) . Part of the above discrepancies may be explained by the report that nigrescens is more abundant in the southeastern United States compared with farther west (Creighton, 1950: 65). Perhaps of more importance are the precise habitats of the two species. In Kansas, opacithorax has been found in open fields, and in park-like areas within cities. Neivamyrmex nigrescens, on the other hand, has not been found in these areas but was found within more moist wooded areas. Although this conclusion has been based on a total of only about 15 colonies of the two species found in Kansas, it suggests that opacithorax may be restricted to drier areas throughout the country.

Raids of Neivamyrmex opacithorax

Neivamyrmex opacithorax appears to feed almost exclusively on ants and carabid beetles. The capturing of larval and adult Carabidae seems to be a common occurrence since three colonies of opacithorax in Kansas had killed numerous specimens, and Wheeler and Long (1901: 163) reported that opacithorax in Texas had captured "a considerable number of small carabid beetles.” Ants probably are more frequently killed in all localities, and ant larvae taken from raid columns showed no movement, probably indicating that they are killed by stings of the army ants at the time of capture. Workers from three colonies showed little attraction toward pecans, English walnuts or roasted peanuts, but two workers at one time chewed on a piece of walnut for about five seconds.

Raids of opacithorax primarily occur in the evening, night and early morning. On cloudy days raids may be extended throughout the day, but the ants rarely raid in sunlight. In all cases the raids seen were column raids with no tendency toward swarm raids. On several but not all raid columns each incoming ant carried a piece of booty. It appears that opacithorax may be more efficient than the common species of Eciton in that fewer opacithorax workers return without prey. It is uncommon to see two or more workers of opacithorax carrying a single piece of booty, whereas such tandem carriers are frequent among Eciton spp. The column raids of opacithorax look inefficient at capturing prey since the ants do not run up low vegetation including even short blades of grass. Numerous insects retreat a few centimeters up on objects and completely escape the ants. The raid columns often show greater fluctuations in traffic than those of most army ants observed, but the fluctuations are not as great as those seen along raid columns of Neivamyrmex pilosus.

Some additional information on the raiding of this species is given by Schneirla (1958a).

Emigrations of Neivamyrmex opacithorax

Three emigrations of opacithorax have been seen in Lawrence, Kansas. The first one found occurred on 3 June 1958 starting probably about 10: 00 p. m. When colony E-263 was first visited at 10:25 p. m. that night, there were no raid columns, and a steady emigration column extended from one hole in the ground to a second hole under a dense bush 50 cm. away. The exact location of the subterranean bivouac(s) is unknown, but since 26 May the ants had raided daily coming out of one or more of five holes within a radius of 16 cm. If one considers 26 May as the first statary day, the ants were emigrating on the ninth statary day or approximately the middle of the statary phase. From 10:25 until 11:10 p.m. the emigration column increased in width slightly until it was between three and five ants wide. No callows were seen in the column, and the brood being carried was in the egg stage. By 11:35 p. m. guard workers had positioned themselves along the column. Some of these became quite excited partly due to my collecting. In addition, a lycosid spider walked across the column, and a sowbug and a caterpillar started to walk across and retreated. The caterpillar was severely attacked; however, the other arthropods were not injured. The excited guard workers sometimes climbed as high as two centimeters up on vegetation, and sometimes ran about six centimeters out from the emigration column. At six minutes past midnight the physogastric queen came walking along the column. The column was highly aroused by that time, and there was no discernible wave of excitement due to the advance of the queen. It is possible that the queen had some difficulty getting through the hole in the ground which was just large enough for her to pass. A solid row of guard workers was along 50 cm of the epigaeic route, but these guard workers were not arranged in a compact wall or tunnel as had been observed with Labidus praedator and other army ants. The queen had about six workers on her in the emigration column, but these were riding and in no way helping her progress along the column. In spite of appearing to be in a maximally physogastric condition, the queen had no obvious difficulty running along the column. The workers of opacithorax, like those of other species of army ants, can run appreciably faster than the queen on a level surface. Most of the egg brood was carried before the queen was seen, but additional brood was carried up until about 12:28 a. m. By this time the number of guard workers had markedly decreased in number, but the width of the column remained approximately the same. By 12:34 a. m. all the guard workers had left, and occasionally a packet of eggs was carried by. Before the queen emigrated, one could see more than 25 packets of eggs along a stretch of column 30 cm. long, but by 12:34 a. m. a maximum of one packet per 30 cm. could be found. Between 12:40 and 12:51 a. m. the column got abruptly thinner, more ants seemed to hesitate and go back along the column a few centimeters, and the first two workers were seen being carried. Several ants were seen to walk more or less sideways, hesitating and picking up dirt and pieces of wood. These workers appeared to be a clean-up squad checking to see whether anything had been left behind. The behavior, which is not seen along the emigration column when it is thronged with actively moving ants, probably is responsible for the carrying of workers and guests more at the end of emigrations rather than during the beginning and middle periods. At 12:54 a. m. the last ants had passed. The end of this emigration made slow progress since the ants ran back along the column and also constantly ran five to ten centimeters laterally from the trail. The caterpillar which had been attacked about 11:40 p.m. was gradually abandoned during the last half hour of the emigration. It struggled constantly while the ants were attacking it and was unable to crawl when abandoned. Observations continued along the trail until 1:31 a. m.; and although no further ants passed, a few phorids and staphylinids were seen.

In addition to the large number of eggs seen being carried on the emigration, the queen from the above colony laid about 9,500 eggs after she was taken. As far as could be determined she did not eat during this period. (More details of the oviposition are given below in the section Oviposition and Queens of Neivamyrmex opacithorax. ) The exact location of neither bivouac is known; but since the epigaeic emigration column was just 50 cm. long, it is highly probable that this was not a normal emigration. Similar short "emigrations" or bivouac shifts of Eciton hamatum and Eciton burchellii have been seen during the statary phase. However, the bivouacs of these two tropical species had been disturbed, and the bivouac sites in some cases had been completely destroyed. There was no known disturbance of the bivouac of this colony of opacithorax. The holes used by the ants were at the edge of a driveway, and it is possible that the bivouac was under the driveway and in too hot and dry a location for the ants. One colony of Neivamyrmex nigrescens emigrated during the statary phase when the queen was nearly maximally contracted, and this emigration was thought to be due to disturbance by a colony of Pheidole (Schneirla, 1958: 231-232; pers. com.)

Not a single callow worker, pupa, or larva was seen in the emigration. Although Schneirla (1958a) has given good evidence to support the hypothesis that Neivamyrmex nigrescens has a nomadic-statary cycle homologous to E. hamatum, there is no comparable evidence for Neivamyrmex opacithorax. This emigration of colony E-263 was undoubtedly atypical since it occurred in the middle of the oviposition period. At that time one would expect a brood of pupae to be present, and perhaps the absence of this older brood was partially responsible for the unusual emigration. (It is unlikely that an entire pupal brood would have been carried by a subterranean route or remained in a subterranean bivouac while the rest of the colony emigrated on the surface.) It is highly improbable that the egg brood formed during the emigration on 3 June 1958 was the first brood of the year. Neiv. opacithorax has raids on the surface of the ground and can be found in clusters under stones in Lawrence, Kansas, at least as early as 10 April. Broods probably are not produced during the winter, and it is not known when the first eggs are laid in the spring.

On the evening of 4 June about 18 hours after the queen of colony E-263 was taken there was no backtracking column at 6:20 p. m.; however, at 10:15 p. m. a column was going toward the old bivouac site but into a hole about 18 cm. closer to the new bivouac than the exit hole used on the emigration. Thus, the ants were not backtracking along the trail actually used on the emigration but were using a different route of an earlier raid column. A few workers occasionally stuck their heads out of the exit hole used on the emigration, but no workers formed a connecting column on the surface of the ground. Two workers which had been kept in the laboratory with the queen were placed along the backtracking column. There was an immediate wave of excitement followed by an increase in the number of workers along the column. On 5 June a backtracking column was still present, and no further observations were made.

Another emigration (colony E-264) was watched on 6 July 1959 on the campus of the University of Kansas. A raid column had been seen crossing a sidewalk next to Snow Hall during the day at 11:30 a. m. and 12:40 p. m. At these times the ants were going out on the column at a rate of about 50 ants in one minute and six seconds. Less than ten percent of the number of ants going out were returning. By 7:15 p. m. the column had increased to 50 ants going out in ten to 20 seconds with less than five ants going toward the bivouac in the same interval. By 8:45 p. m. traffic was more steady at about 50 ants going out and nearly 12 going in during 12 seconds. Booty was first seen being carried out at 8:53 p.m., and by 8:56 p.m. larval brood was carried. At this time approximately two percent of the ants carried either booty or brood. However, at 9:02 p. m. the amount of brood increased markedly until about 507c of the workers were carrying brood, and the traffic had increased to its maximum of about 50 ants going out in five seconds. At 11:22 p. m. the ants became more excited, workers ran one to five centimeters away from the column along both sides, and many more workers ran back toward the old bivouac. The queen was taken at 11:41 p. m. Up until 1:35 a. m. on 7 July when observations were ended, the number of ants going toward the new bivouac remained at the maximal rate, and workers went back toward the old bivouac at about 25% of the outward rate. Many callows and a few minor worker pupae were seen in the emigration. Only dark workers were seen returning toward the old bivouac and carrying other workers.

A strong backtracking column was found along the emigration trail between 10:00 a. m. and 1:00 p. m. on 7 July. The column consisted solely of dark workers running in both directions in approximately equal numbers. At 8:00 and 9:00 p.m. the traffic on the backtracking column was the same or slightly stronger. At 7:45 a. m. the following morning the traffic on the column had decreased from its previous strength at night, and the first callow was seen in the column. The column continued throughout the day, and the first brood or booty was seen being carried toward the old bivouac (of 6 July) at 7:00 p. m. The backtracking column persisted until 10 July when it was noticeably weaker at 10:00 a. m. compared to previous days at that time. On 10 July at 6:00 p. m. and the entire following day there were no longer any ants along the trail.

A third emigration (colony E-266) was watched almost continuously from 9:00 p.m. to 3:20 a.m. on 19 to 20 August 1959. Throughout this period numerous callows were seen, and booty and a brood of worker larvae about three-fourths grown were being carried. The queen was not seen, and neither guard workers nor greatly excited running workers were seen, indicating that she probably had not emigrated before 3:20 a. in. On 20 August at 7:30 p. 111. there was a weak column of about one ant per ten centimeters (including the approximately equal traffic in both directions). This column had disappeared by the following morning, and it is impossible to determine whether it was a backtracking column (possibly followed by a continuation of the emigration) or a raid column. Similar columns along previous emigration routes have also been reported for nigrescens (Schneirla, 1958a), but such columns are not found or are rare among Eciton spp.

Bivouacs of Neivamyrmex opacithorax

All bivouacs of opacithorax which have been located were subterranean, and their exact positions and sizes are unknown. On five occasions in the vicinity of Lawrence, Kansas, clusters of opacithorax have been found under small stones. Each of these clusters was considered to be less than five per cent of the total colony. Similar "bivouacs" under stones mentioned by Schneirla (1958a) probably were not entire colonies. Brood was never found in any of the clusters in Kansas except for the adult males in colony E-267 discussed below. However, opacithorax like nigrescens probably brings at least part of its brood up from more subterranean bivouacs to areas under stones on the surface of the ground. These stones were all exposed to bright sunlight during the day, and an unusually high number of staphylinid beetles or mounds of loose dirt indicated that the ants had been much more numerous under each stone than they were at the time they were found.

Oviposition and Queens of Neivamyrmex opacithorax

The queen from colony E-263 in the laboratory laid 9,500 eggs within 42 hours of the time when she was taken from an emigration column. This rate of oviposition is 226 per hour or 3.8 per minute, judging from the few colonies which I have seen, the colonies and broods of opacithorax and nigrescens are essentially the same size. At the above oviposition rate it would take the queen almost seven days to lay a brood of 37,000 eggs. A brood of that size was considered to be average for Neiv. nigrescens (Schneirla, 1958a: 242- 243). However, it is known from observations on physogastric Eciton queens that when these queens are brought into the laboratory, they cease laying sooner than if left with their colonies. In addition, Eciton and Neivamyrmex queens become noticeably weak and often die within a few days in the laboratory. As a consequence the oviposition rate in a normal bivouac may be considerably higher. Records for the first 19 hours indicate that queen E-263 laid at a rate close to 300 per hour which is probably closer to the rate in a bivouac. At this rate she could have laid a brood of 36,000 eggs in five days.

Actual egg laying occurred in irregular spurts with sometimes more than five minutes between two groups of eggs. The eggs most frequently were laid in groups of two to eight eggs stuck together at their tips. Five or six eggs usually were laid in 30 seconds. The eggs appeared moist when laid and readily stuck together in packets without licking or handling by the workers. The queen often rested partially on her side when ovipositing and frequently walked around the dish scattering eggs wherever she went. The workers gathered up most of the eggs and placed them in piles. Several workers ate some eggs while turning their abdomens under as if they were stinging the eggs at the same time. It is not known whether the workers also eat eggs or other brood in a bivouac, but it is a well-known fact that other Ecitonini eat their brood of all ages more readily in the laboratory than under field conditions. The queen was kept alive until 6:00 p. m. on 5 June 1958 when she was placed in Bouin's fixative. No eggs had been laid during the preceding hour, and only a few were laid in the last three hours before preserving the queen. As far as we could determine the queen did not eat nor drink anything while she was in the laboratory. The queen from colony D-175 taken by Howell V. Dalv from a cluster under a stone also was never seen to feed, but the workers with her readily drank water and fed on a partially crushed housefly. This queen was observed to clean her own antennae with her front legs, but no queen of Neivamyrmex, Nomamyrmex nor Eciton was observed to clean any part of her body. All queens of Ecitonini usually ran around with their mandibles spread, but they would never bite anything even if an object was placed between the mandibles.

Sexual Broods of Neivamyrmex opacithorax

Colony E-267 was found about 2:00 p.m. on 21 October 1959 by people who complained that their home was being invaded by insects coming up between floor boards. Investigation on the following day at 10:00 a. m. showed that the colony had a brood of alate males which were entering the house along with some workers, and additional males were at the edges of the foundation on opposite sides of the house. Workers were more numerous along the inside edges of the foundation where small clusters of up to 200 workers were scattered for more than a meter along the rough field stone foundation. No brood other than the adult males could be found, and the largest part of the colony (or colonies) must have been under the foundation. Most of the males had a number of workers clinging to them. The two groups of ants were about six meters apart with no ants seen between the opposite sides of the house externally or in the crawl space under the house. These two groups may have been daughter colonies following a colony division.

A total of 52 males was taken and 27 of these were kept alive in a laboratory nest. When placed in this nest at 1:00 p.m. on 22 October, three of these 27 males ran around the nest, tried to fly and were attracted toward a microscope light. Several males clustered with workers on a petri dish filled with moist cotton. Most of the males clearly moved away from the light and slowly walked until they reached the darker corners of the nest. These latter males neither fanned their wings nor flew when dropped. Most of the males had died by the morning of 24 October. The workers pulled the dead males around the laboratory nest a little but did not eat any part of the males nor do any damage to them. A circular column was found on 25 October at 2:00 p. m. after the males had all died. This column continued for over six hours without an interruption even though the cover of the nest was removed and lights were turned on and off repeatedly.

Atchison & Lucky (2022) found that this species, as expected, does not remove seeds.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Myrmecopria mellea (a parasite) (www.diapriid.org).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Apopria sp. (a parasite) (www.diapriid.org) (potential host).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Apopria coveri (a parasite) (Masner & Garcia, 2002) (potential host).

- This species is a associate (details unknown) for the phorid fly Acontistoptera melanderi (a associate (details unknown)) (Quevillon, 2018).

- This species is a associate (details unknown) for the phorid fly Xanionotum hystrix (a associate (details unknown)) (Quevillon, 2018).

- This species is a associate (details unknown) for the phorid fly Xanionotum wasmanni (a associate (details unknown)) (Quevillon, 2018).

- This species is a host for the phorid fly Megaselia sp. (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

Life History Traits

- Queen number: monogynous (Rissing and Pollock, 1988; Frumhoff & Ward, 1992)

Castes

Worker

| |

| Syntype of Neivamyrmex opacithorax. . | Owned by Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

| |

| . | Owned by Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

| |

| . | Owned by Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0104139. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0104142. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0005334. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by UCDC, Davis, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0102767. Photographer Jen Fogarty, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Queen

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0104855. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Male

| |

| Photographer Gordon Snelling. | |

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0104138. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- opacithorax. Eciton (Acamatus) californicum subsp. opacithorax Emery, 1894c: 184 (diagnosis in key) (w.) U.S.A. (Missouri).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: U.S.A.: Missouri, Ripley County, Doniphan (Pergande).

- Type-depositories: MCZC, MHNG, MSNG, USNM.

- Wheeler, W.M. & Long, 1901: 163, 173 (m.q., respectively); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1984: 273 (l.).

- Combination in E. (Neivamyrmex): Smith, M.R. 1942c: 555;

- combination in Neivamyrmex: Borgmeier, 1953: 5.

- Subspecies of californicus: Emery, 1895c: 259 (description); Pergande, 1896: 874.

- Status as species: Emery, 1900a: 186; Wheeler, W.M. & Long, 1901: 163; Wheeler, W.M. 1904e: 300; Wheeler, W.M. 1908e: 411; Emery, 1910b: 25; Wheeler, W.M. 1910g: 562; Wheeler, W.M. 1913c: 113; Smith, M.R. 1930a: 2; Wheeler, W.M. 1932a: 2; Smith, M.R. 1938b: 158; Smith, M.R. 1942c: 555 (redescription); Buren, 1944a: 280; Creighton, 1950a: 74; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 781; Cole, 1953c: 84; Borgmeier, 1955: 502 (redescription); Smith, M.R. 1958c: 109; Carter, 1962a: 6 (in list); Smith, M.R. 1967: 345; Watkins, 1971: 94 (in key); Kempf, 1972a: 157; Watkins, 1972: 349 (in key); Hunt & Snelling, 1975: 21; Watkins, 1976: 16 (in key); Smith, D.R. 1979: 1332; Watkins, 1982: 211 (in key); Watkins, 1985: 482 (in key); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1986g: 19 (in key); Mackay, Lowrie, et al. 1988: 87; Deyrup, et al. 1989: 94; Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1990a: 461; Bolton, 1995b: 290; Ward, 1999a: 90 (in key); Mackay & Mackay, 2002: 62; Deyrup, 2003: 45; MacGown & Forster, 2005: 67; Ward, 2005: 62; Snelling, G.C. & Snelling, 2007: 487; Branstetter & Sáenz, 2012: 254; Deyrup, 2017: 38.

- Senior synonym of castaneum: Borgmeier, 1955: 502; Smith, M.R. 1958c: 109; Kempf, 1972a: 157; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1332; Bolton, 1995b: 290; Snelling, G.C. & Snelling, 2007: 487.

- Distribution: Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, U.S.A.

- castaneum. Eciton (Acamatus) opacithorax var. castaneum Borgmeier, 1939: 416 (w.) COSTA RICA.

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated, “numerous”).

- Type-locality: Costa Rica: San José (H. Schmidt).

- Type-depository: MZSP.

- Borgmeier, 1948a: 192 (q.m.).

- Combination in E. (Neivamyrmex): Borgmeier, 1948a: 191;

- combination in Neivamyrmex: Borgmeier, 1953: 5.

- Subspecies of opacithorax: Borgmeier, 1948a: 191 (redescription).

- Junior synonym of opacithorax: Borgmeier, 1955: 502; Smith, M.R. 1958c: 109; Kempf, 1972a: 157; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1332; Bolton, 1995b: 288; Snelling, G.C. & Snelling, 2007: 487.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Smith (1942) - Major. Length 4-5 mm.

Head approximately as broad as long, narrowed posteriorly; posterior border emarginate, forming produced, angular corners which are not clearly curved outwardly as in wheeleri. Eye ocellus like, distinct, though usually less perceptible than that of nigrescens because of the less opaque background. Margin on superior border of mandible between basal tooth and masticatory border straight (excised in commutatum, convex in nigrescens). Antennal scape robust, long, three and three-fourths to four and one-third times as long as broad; when extended backward, noticeably surpassing posterior border of eye; funiculus not noticeably robust, segments 2 to 4 inclusive, approximately as broad as long. Frontal carina not forming a broad, pellucid flange in front of antennal socket as is wheeleri. Thorax, from above, with convex dorsum and usually a very distinct transverse pronotal carina; side of prothorax extending above .fore coxa as a somewhat reflexed lobe. Promesonotum, in profile, forming a rather long, even, gentle arch, which is slightly elevated above epinotum. Meso-epinotal constriction weakly indicated in some specimens, well defined in others. Base and declivity of epinotum subequal, the two surfaces meeting to form a distinct, obtuse angle. Petiole somewhat slender, clearly longer than broad (approximately five-eighths as broad as long), of same general shape as that of nigrescens; with anteroventral tooth. Postpetiole, from above, very slightly shorter but distinctly broader than petiole, subtrapezoidal, almost as long as broad.

Mandible opaque in some lights; bearing longitudinal striae and scattered piligerous punctures. Head smooth and shining or very delicately shagreened, with distinct but scattered punctures; posterior corners often with a few foveolate impressions. Thorax opaque, bearing dense, granulate punctures which are dorsally interspersed with scattered foveolate impressions (foveolate impressions similar to those of nigrescens but never so coarse or abundant); propleura, and sometimes the meso- and meta pleura, slightly shining. Petiole with sculpturing similar to that of thorax but never so coarse, thus subopaque rather than opaque. Postpetiole usually, and gaster always, smooth and shining.

Hairs grayish or yellowish, rather abundant, suberect to erect, of various lengths, some strikingly long; some of the hair on gaster shorter and more appressed than elsewhere.

Light to dark reddish brown; thorax usually darkest; gaster and legs lighter than head and petiole.

Queen

Smith (1942) - Length 15 mm.

Head approximately as long as broad; broadest anteriorly; with rounded posterior corners and weakly emarginated posterior border. Eye ocellus like, small and indistinct, slightly closer to posterior border than to anterior border. Mandible elongate, narrow, with somewhat subparallel superior and inferior borders, superior border obliquely descending near apex to form a distinct, sharp-pointed tooth. Scape curved, robust, approximately one-half length of head. Region adjacent to and also somewhat posterior to frontal area with a strong, transverse, angular anterior protuberance. A deep median groove extending from clypeus toward vertex, becoming weaker posteriorly. Dorsal surface of clypeus concave, middle of anterior border broadly, but not deeply excised. Dorsal surface of head with a distinct median impression near occipital border, and a faint groove extending anteriorly. Posterior corners feebly produced, not tuberculate and not sharply angulate. Thorax, from above, approximately twice as long as wide, gradually increasing in width posteriorly; epinotum not so wide as head. Promesonotal, mesometanotal, and meta-epinotal sutures distinct. Pronotum about as long as broad, marginate anteriorly and submarginate laterally. Mesonotum with somewhat angular anterior border and a more broadly angular posterior border. Epinotum broader than long, with bluntly angular posterior corners. Mesonotum with very feeble, scarcely discernible, longitudinal median impression; epinotum with a much broader and deeper impression. Thorax, in profile, approximately 3 times as long as high. Petiole about as high as epinotum but not so long; with a large, convex protuberance or tooth beneath; from above, one and one-third to one and one-half times as broad as long, with convex sides and a longitudinal median impression, which noticeably widens posteriorly. Gaster elongate.

Thorax opaque owing to the dense granulate shagreening and the numerous coarse, scattered punctures. Head rather shining because of the finer sculpturing. Petiole more feebly sculptured than thorax but scarcely as shining as dorsal surface of head.

Hairs yellowish, short; rather abundant on head, thorax, petiole, and appendages; mandibles, clypeus, gula, and scapes with longer hairs of various lengths.

Ferruginous brown with legs and antennal scapes lighter; frontal groove, borders of mandible, and clypeus darker.

Male

Smith (1942) - Length 10-11 mm.

Head approximately one and seven-tenths times as broad as long; posterior border well rounded. Eye rather ~mall, moderately convex, protuberant. Ocelli very small, placed on low protuberance, which is scarcely raised above general surface of head; summit of protuberance concave. Frontal carinae converging behind, with distinct median groove between them leading to anterior ocellus. Ridge above antennal socket scarcely perceptible. Middle of anterior border of dypeus straight or feebly excised. Antenna rather slender; scape approximately as long as combined length of first 3 funicular segments; funiculus subfiliform, very slightly broadened through segments 2 to 6 inclusive, all segments except first distinctly longer than wide. Mandible moderately elongate to noticeably elongate, with somewhat subparallel superior and inferior borders basally; superior border sloping obliquely toward inferior border at approximately apical third of mandible to form a rather blunt tip. Head, from above. not noticeably extended behind eyes, with well-rounded corners which blend evenly into eyes; dorsum rather convex, rounding off anteriorly in such a manner that the ridge above the antennal socket is either absent or feebly developed. Lateral ocellus far removed from eye, space between the two almost equivalent to space between the two lateral ocelli. Eye, in profile, narrowed above, not occupying all of side of head, there being a small area ventrad and mesad of it, and a very much larger area posterodorsad. Region of head posterior to ocelli convex, without occipital flange. Thorax not projecting prominently above head. Prothorax with distinct transverse impression anteriorly. Mesonotum with rather distinct anteromedian and parapsidal lines. Epinotal declivity appearing subtruncate but really concave. Gaster slender to moderately robust; sixth gastric tergum with a transverse impression near base. Seventh gastric sternum with 2 acute lateral teeth and a somewhat blunter intermediate tooth. Paramere, in profile, with a distinct median excision on the ventral border and a prominent basal, ventral angle.

All parts of body and appendages more or less shining in certain lights except the funiculi, and sometimes the dorsal surface of petiole. Head especially shining regardless of the punctures scattered over it. Sides and dorsum of thorax wtih numerous, distinct punctures; punctures, however, not obscuring the rather shining surface.

Hairs light yellowish to deep yellowish; suberect to erect on scape, head, legs, and venter of thorax and petiole; more appressed on dorsum of thorax and especially on the gaster.

Head, thorax, petiole, legs, and sometimes base of first gastric segment blackish; mandibles, funiculi, tarsi, and gaster light brown or reddish brown. Wings ranging from very feebly infuscated to blackish, the veins and stigma brownish black or black.

Type Material

Smith (1942) - Cotypes in the United States National Museum

Etymology

Morphological. The term translates as "dark thorax."

References

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Albuquerque, E., Prado, L., Andrade-Silva, J., Siqueira, E., Sampaio, K., Alves, D., Brandão, C., Andrade, P., Feitosa, R., Koch, E., Delabie, J., Fernandes, I., Baccaro, F., Souza, J., Almeida, R., Silva, R. 2021. Ants of the State of Pará, Brazil: a historical and comprehensive dataset of a key biodiversity hotspot in the Amazon Basin. Zootaxa 5001, 1–83 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5001.1.1).

- Atchison, R. A., Lucky, A. 2022. Diversity and resilience of seed-removing ant species in Longleaf Sandhill to frequent fire. Diversity 14, 1012 (doi:10.3390/d14121012).

- Borgmeier, T. 1953. Vorarbeiten zu einer Revision der neotropischen Wanderameisen. Stud. Entomol. 2: 1-51 (page 5, Combination in Neivamyrmex)

- Borgmeier, T. 1955. Die Wanderameisen der neotropischen Region. Stud. Entomol. 3: 1-720 (page 502, Senior synonym of castaneum)

- Borowiec, M.L. 2019. Convergent evolution of the army ant syndrome and congruence in big-data phylogenetics. Systematic Biology 68, 642–656 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syy088).

- Davis, T. 2009. The ants of South Carolina (thesis, Clemson University).

- Deyrup, M.A., Carlin, N., Trager, J., Umphrey, G. 1988. A review of the ants of the Florida Keys. Florida Entomologist 71: 163-176.

- Emery, C. 1894d. Studi sulle formiche della fauna neotropica. VI-XVI. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Ital. 26: 137-241 (page 184, diagnosis in key, worker described)

- Emery, C. 1900e. Nuovi studi sul genere Eciton. Mem. R. Accad. Sci. Ist. Bologna (5)8:173-188 (page 186, Raised to species)

- Flores-Maldonado, K. Y.; Phillips, S. A., Jr.; Sánchez-Ramos, G. 1999. The myrmecofauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) along an altitudinal gradient in the Sierra Madre Oriental of northeastern Mexico. Southwest. Nat. 44: 457-461 (page 457, record in Mexico)

- Ipser, R.M., Brinkman, M.A., Gardner, W.A., Peeler, H.B. 2004. A survey of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Georgia. Florida Entomologist 87: 253-260.

- MacGown, J.A., Booher, D., Richter, H., Wetterer, J.K., Hill, J.G. 2021. An updated list of ants of Alabama (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with new state records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 147: 961-981 (doi:10.3157/061.147.0409).

- Masner, L., and J. L. Garcia. 2002. The Genera of Diapriinae (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) in the New World., 138 pp..

- Snelling, G. C.; Snelling, R. R. 2007. New synonymy, new species, new keys to Neivamyrmex army ants of the United States. In Snelling, R. R., B. L. Fisher, and P. S. Ward (eds). Advances in ant systematics (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): homage to E. O. Wilson - 50 years of contributions. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 80:459-550. PDF

- Schultner, E., Pulliainen, U. 2020. Brood recognition and discrimination in ants. Insectes Sociaux 67, 11–34 (doi:10.1007/s00040-019-00747-3).

- Smith, M. R. 1942c. The legionary ants of the United States belonging to Eciton subgenus Neivamyrmex Borgmeier. Am. Midl. Nat. 27: 537-590 (page 555, Combination in E. (Neivamyrmex))

- Varela-Hernández, F., Medel-Zosayas, B., Martínez-Luque, E.O., Jones, R.W., De la Mora, A. 2020. Biodiversity in central Mexico: Assessment of ants in a convergent region. Southwestern Entomologist 454: 673-686.

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1984a. The larvae of the army ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): a revision. J. Kans. Entomol. Soc. 57: 263-275 (page 273, larva described)

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1990a [1989]. Notes on ant larvae. Trans. Am. Entomol. Soc. 115: 457-473 (page 461, see also)

- Wheeler, W. M.; Long, W. H. 1901. The males of some Texan Ecitons. Am. Nat. 35: 157-173 (page 163, male described; page 173, queen described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Annotated Ant Species List Ordway-Swisher Biological Station. Downloaded at http://ordway-swisher.ufl.edu/species/os-hymenoptera.htm on 5th Oct 2010.

- Borgmeier T. 1936. Sobre algumas formigas dos generos Eciton e Cheliomyrmex (Hym. Formicidae). Archivos do Instituto de Biologia Vegetal (Rio de Janeiro) 3: 51-68.

- Borgmeier T. 1948. Die Geschlechtstiere zweier Eciton-Arten und einige andere Ameisen aus Mittel- und Suedamerika (Hym. Formicidae). Revista de Entomologia (Rio de Janeiro) 19: 191-206.

- Borgmeier T. 1955. Die Wanderameisen der neotropischen Region. Studia Entomologica 3: 1-720.

- Cokendolpher J. C., and O. F. Francke. 1990. The ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of western Texas. Part II. Subfamilies Ecitoninae, Ponerinae, Pseudomyrmecinae, Dolichoderinae, and Formicinae. Special Publications, the Museum. Texas Tech University 30:1-76.

- Cokendolpher J.C., Reddell J.R., Taylor S.J, Krejca J.K., Suarez A.V. and Pekins C.E. 2009. Further ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from caves of Texas [Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicdae) adicionales de cuevas de Texas]. Texas Memorial Museum Speleological Monographs, 7. Studies on the cave and endogean fauna of North America, V. Pp. 151-168

- Cover S. P., and R. A. Johnson. 20011. Checklist of Arizona Ants. Downloaded on January 7th at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/AZants-2011%20updatev2.pdf

- Dash S. T. and L. M. Hooper-Bui. 2008. Species diversity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Louisiana. Conservation Biology and Biodiversity. 101: 1056-1066

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Des Lauriers J., and D. Ikeda. 2017. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the San Gabriel Mountains of Southern California, USA with an annotated list. In: Reynolds R. E. (Ed.) Desert Studies Symposium. California State University Desert Studies Consortium, 342 pp. Pages 264-277.

- Deyrup M. 2016. Ants of Florida: identification and natural history. CRC Press, 423 pages.

- Deyrup M., C. Johnson, G. C. Wheeler, J. Wheeler. 1989. A preliminary list of the ants of Florida. Florida Entomologist 72: 91-101

- Deyrup M., L. Deyrup, and J. Carrel. 2013. Ant Species in the Diet of a Florida Population of Eastern Narrow-Mouthed Toads, Gastrophryne carolinensis. Southeastern Naturalist 12(2): 367-378.

- Deyrup, M. and J. Trager. 1986. Ants of the Archbold Biological Station, Highlands County, Florida (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Florida Entomologist 69(1):206-228

- Deyrup, Mark A., Carlin, Norman, Trager, James and Umphrey, Gary. 1988. A Review of the Ants of the Florida Keys. The Florida Entomologist. 71(2):163-176.

- DuBois M. B. 1981. New records of ants in Kansas, III. State Biological Survey of Kansas. Technical Publications 10: 32-44

- DuBois M. B. 1985. Distribution of ants in Kansas: subfamilies Ponerinae, Ecitoninae, and Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 11: 153-316

- DuBois M. B. 1985. Distribution of ants in Kansas: subfamilies Ponerinae, Ecitoninae, and Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 11: 153-318

- DuBois M. B. 1985. Distribution of ants in Kansas: subfamilies Ponerinae, Ecitoninae, and Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 11: 153-319

- DuBois M. B. 1985. Distribution of ants in Kansas: subfamilies Ponerinae, Ecitoninae, and Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 11: 153-320

- DuBois M. B. 1985. Distribution of ants in Kansas: subfamilies Ponerinae, Ecitoninae, and Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 11: 153-321

- DuBois M. B. 1985. Distribution of ants in Kansas: subfamilies Ponerinae, Ecitoninae, and Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 11: 153-322

- DuBois M. B. 1985. Distribution of ants in Kansas: subfamilies Ponerinae, Ecitoninae, and Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 11: 153-323

- DuBois M. B. 1985. Distribution of ants in Kansas: subfamilies Ponerinae, Ecitoninae, and Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 11: 153-324

- DuBois M. B. 1985. Distribution of ants in Kansas: subfamilies Ponerinae, Ecitoninae, and Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 11: 153-325

- Emery C. 1895. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. (Schluss). Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Tiere 8: 257-360.

- Emery C. 1910. Hymenoptera. Fam. Formicidae. Subfam. Dorylinae. Genera Insectorum 102: 1-34.

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Flores-Maldonado K. Y., S. A. Phillips, and G. Sanchez-Ramos. 1999. The myrmecofauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) along an altitudinal gradient in the Sierra Madre Oriental of Northeastern Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 44(4): 457-461.

- Flores-Maldonado, K. Y., S. A. Phillips-Jr, and G. Sanchez-Ramos. 1999. The myrmecofauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) along an altitudinal gradient in the Sierra Madre Oriental of Northeastern Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 44: 457-461.

- Gans M. J., J. R. Arnold, A. Cohuo, L. Castro, D. Lam, and C. Wiley. 2016. Survey of ant species in Rockwall County, Texas. Southwestern Entomologist 41(2): 373-378.

- Gove, A. D., J. D. Majer, and V. Rico-Gray. 2009. Ant assemblages in isolated trees are more sensitive to species loss and replacement than their woodland counterparts. Basic and Applied Ecology 10: 187-195.

- Guénard B., K. A. Mccaffrey, A. Lucky, and R. R. Dunn. 2012. Ants of North Carolina: an updated list (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 3552: 1-36.

- Hernandez, F. Varela and G. Castano-Meneses. 2010. Checklist, Biological Notes and Distribution of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Barranca de Metztitlán Biosphere Reserve, Hidalgo, Mexico. Sociobiology 56(2):397-434

- Hess C. G. 1958. The ants of Dallas County, Texas, and their nesting sites; with particular reference to soil texture as an ecological factor. Field and Laboratory 26: 3-72.

- Johnson C. 1986. A north Florida ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insecta Mundi 1: 243-246

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Johnson, R.A. and P.S. Ward. 2002. Biogeography and endemism of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Baja California, Mexico: a first overview. Journal of Biogeography 29:10091026/

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- LeBrun E. G., R. M. Plowes, and L. E. Gilbert. 2015. Imported fire ants near the edge of their range: disturbance and moisture determine prevalence and impact of an invasive social insect. Journal of Animal Ecology,81: 884–895.

- Lubertazzi D. and Tschinkel WR. 2003. Ant community change across a ground vegetation gradient in north Floridas longleaf pine flatwoods. 17pp. Journal of Insect Science. 3:21

- MacGown J. A., J. G. Hill, and M. Deyrup. 2009. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Little Ohoopee River Dunes, Emanuel County, Georgia. J. Entomol. Sci. 44(3): 193-197.

- MacGown J.A., Hill J.G. and Skvarla M. 2011. New Records of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) for Arkansas with a Synopsis of Previous Records. Midsouth Entomologist. 4: 29-38

- Macgown J. A., S. Y. Wang, J. G. Hill, and R. J. Whitehouse. 2017. A List of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Collected During the 2017 William H. Cross Expedition to the Ouachita Mountains of Arkansas with New State Records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society, 143(4): 735-740.

- Mackay W. P., and E. E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 400 pp.

- Mackay, W., D. Lowrie, A. Fisher, E. Mackay, F. Barnes and D. Lowrie. 1988. The ants of Los Alamos County, New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). pages 79-131 in J.C. Trager, editor, Advances in Myrmecololgy.

- Moreau C. S., M. A. Deyrup, and L. R. David Jr. 2014. Ants of the Florida Keys: Species Accounts, Biogeography, and Conservation (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Insect Sci. 14(295): DOI: 10.1093/jisesa/ieu157

- Morrison, L.W. 2002. Long-Term Impacts of an Arthropod-Community Invasion by the Imported Fire Ant, Solenopsis invicta. Ecology 83(8):2337-2345

- O'Keefe S. T., J. L. Cook, T. Dudek, D. F. Wunneburger, M. D. Guzman, R. N. Coulson, and S. B. Vinson. 2000. The Distribution of Texas Ants. The Southwestern Entomologist 22: 1-92.

- Pergande, T. 1895. Mexican Formicidae. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences Ser. 2 :850-896

- Quiroz-Robledo, L.N. and J. Valenzuela-Gonzalez. 2006. Las hormigas Ecitoninae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Morelos, México. Revista Biologia Tropical 54(2):531-552

- Rojas Fernandez P. 2010. Capítulo 24. Hormigas (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae). In: Diversidad Biológica de Veracruz. Volumen Invertebrados. CONABIO-Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz.

- Smith M. R. 1935. A list of the ants of Oklahoma (Hymen.: Formicidae). Entomological News 46: 235-241.

- Smith M. R. 1936. A list of the ants of Texas. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 44: 155-170.

- Smith M. R. 1942. The legionary ants of the United States belonging to Eciton subgenus Neivamyrmex Borgmeier. American Midland Naturalist 27: 537-590.

- Smith M. R. 1965. House-infesting ants of the eastern United States. Their recognition, biology, and economic importance. United States Department of Agriculture. Technical Bulletin 1326: 1-105.

- Snelling G. C. and R. R. Snelling. 2007. New synonymy, new species, new keys to Neivamyrmex army ants of the United States. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 80: 459-550

- Spiesman B. 2006. On the community of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the sandhills of Florida. . Master of Science, University of Florida. 82 pages.

- Van Pelt A. F. 1948. A Preliminary Key to the Worker Ants of Alachua County, Florida. The Florida Entomologist 30(4): 57-67

- Van Pelt, A. 1983. Ants of the Chisos Mountains, Texas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) . Southwestern Naturalist 28:137-142.

- Vasquez Bolanos M. 1998. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) colectadas en necrotrampas, en tres localidades de Jalisco, Mexico. Thesis in Biological Science, Las Aguijas, Zapopan, Jalisco, 61 pages.

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Ward P. S. 2005. A synoptic review of the ants of California (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 936: 1-68.

- Warren, L.O. and E.P. Rouse. 1969. The Ants of Arkansas. Bulletin of the Agricultural Experiment Station 742:1-67

- Watkins II, J.F. 1982.The army ants of Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Ecitoninae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 55(2): 197-247.

- Watkins J. F., II 1971. A taxonomic review of Neivamyrmex moseri, N. pauxillus, and N. leonardi, including new distribution records and original descriptions of queens of the first two species. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 44: 93-103.

- Watkins J. F., II 1985. The identification and distribution of the army ants of the United States of America (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Ecitoninae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 58: 479-502.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler J. 1989. A checklist of the ants of Oklahoma. Prairie Naturalist 21: 203-210.

- Wheeler W. M. 1904. The ants of North Carolina. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 20: 299-306.

- Wheeler W. M. 1908. The ants of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. (Part I.). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 24: 399-485.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1985. A checklist of Texas ants. Prairie Naturalist 17:49-64.

- Whitcomb W. H., H. A. Denmark, A. P. Bhatkar, and G. L. Greene. 1972. Preliminary studies on the ants of Florida soybean fields. Florida Entomologist 55: 129-142.

- Young J., and D. E. Howell. 1964. Ants of Oklahoma. Miscellaneous Publication. Oklahoma Agricultural Experimental Station 71: 1-42.

- Young, J. and D.E. Howell. 1964. Ants of Oklahoma. Miscellaneous Publications of Oklahoma State University MP-71

- Zettler J. A., M. D. Taylor, C. R. Allen, and T. P. Spira. 2004. Consequences of Forest Clear-Cuts for Native and Nonindigenous Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 97(3): 513-518.

- Photo Gallery

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- Tropical

- Diapriid wasp Associate

- Host of Myrmecopria mellea

- Host of Apopria sp.

- Host of Apopria coveri

- Phorid fly Associate

- Host of Acontistoptera melanderi

- Host of Xanionotum hystrix

- Host of Xanionotum wasmanni

- Host of Megaselia sp.

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Dorylinae

- Neivamyrmex

- Neivamyrmex opacithorax

- Dorylinae species

- Neivamyrmex species

- Ssr