Octostruma montanis

| Octostruma montanis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Octostruma |

| Species: | O. montanis |

| Binomial name | |

| Octostruma montanis Longino, 2013 | |

Octostruma montanis is a cloud forest species known from two sites: Cerro Musún in southern Nicaragua and Monteverde in Costa Rica. Cerro Musún is an isolated mountain surrounded by largely deforested lowlands. The slopes from 700 m elevation to the peak at 1400 m are a protected reserve. The LLAMA project carried out Winkler sampling across the full elevational range of the reserve, and O. montanis was restricted to parts of the reserve above 1100 m. In Monteverde in the Cordillera de Tilarán, northern Costa Rica, O. montanis occurs in the ridge crest cloud forest at 1500 m elevation, but not lower. All collections are from Winkler samples of sifted litter and rotten wood from the forest floor. (Longino 2013)

Identification

Face lacking transverse arcuate carina; basal five teeth of mandible acute; apex of labrum bilobed; face typically with 6 spatulate setae (8 in Octostruma cyrtinotum), seta-bearing pits along vertex margin large; filiform setae lacking on petiole, postpetiole, first gastral sternite; anterior half of dorsal face of propodeum convex, demarcating impressed metanotal groove; mesonotum lacking spatulate setae (with a pair in O. cyrtinotum). (Longino 2013)

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 12.97796° to 12.97056°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Costa Rica, Nicaragua (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

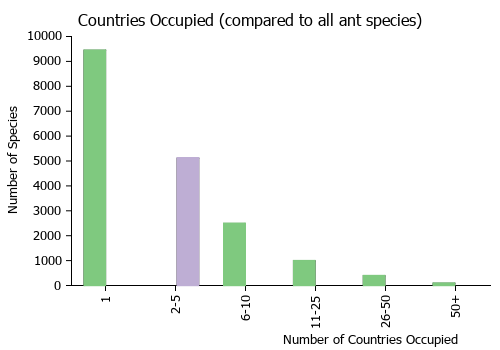

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

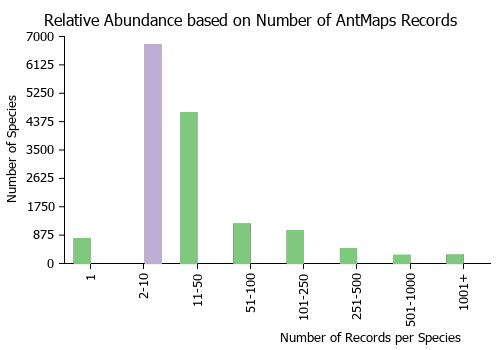

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- montanis. Octostruma montanis Longino, 2013: 43, figs. 1C, 3B, 5P, 32, 43 (w.) NICARAGUA.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Three worker series from Reserva Musún in Nicaragua are uniform in face setal pattern. Two worker series, each of two workers, are known from Monteverde, Costa Rica, and they vary in setal pattern. One series is identical to the Musún specimens, with the same number and disposition of setae, and the same enlarged seta-bearing pits. The other has only the posteromedian seta pair and the pits are not enlarged. The seta pair at the lateral vertex angles and the pair near the eyes are missing and there are no differentiated pits at these sites, so their absence is probably not due to wear. This setal pattern is the same as Octostruma planities, which occurs in the nearby dry-forest lowlands. In all other characters the specimens are like other O. montanis specimens.

Description

Worker

HW 0.73–0.78, HL 0.69–0.72, WL 0.80–0.85, CI 106–109 (n=4). Differing from Octostruma cyrtinotum in the characters of the Diagnosis (see the identification section above); otherwise similar in most respects to O. cyrtinotum.

Type Material

Holotype worker: NICARAGUA, Matagalpa: RN Cerro Musún, 12.97796, -85.23242, ±50 m, 1350 m, 1 May 2011, wet cloud forest, ex sifted leaf litter (R.S.Anderson#2011-008) California Academy of Sciences, unique specimen identifier CASENT0627340]. Paratype workers: same data CASC, CASENT0623873; National Museum of Natural History, CASENT0627338; Museum of Comparative Zoology, CASENT0627339; Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, CASENT0627341]; same data except 12.97056, -85.23388, ±20 m, 1120 m, 2 May 2011 (LLAMA, Wm-D-01-1-06) Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad, CASENT0639986; University of California, Davis, CASENT0639988; CASC, CASENT0639990; John T. Longino Collection, CASENT0639991.

Etymology

The name refers to its restriction to montane habitats. It is a dative plural noun and thus invariant.

References

- Longino, J.T. 2013. A revision of the ant genus Octostruma Forel 1912 (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Zootaxa 3699, 1-61. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3699.1.1

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Longino J. T. 2013. A revision of the ant genus Octostruma Forel 1912 (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Zootaxa 3699(1): 1-61.