Tapinoma sessile

| Tapinoma sessile | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Dolichoderinae |

| Genus: | Tapinoma |

| Species: | T. sessile |

| Binomial name | |

| Tapinoma sessile (Say, 1836) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Common Name | |

|---|---|

| Odorous House Ant | |

| Language: | Enlgish |

This species is extremely adaptable, nesting in a wide range of sites and being found in numerous habitats. Nests in open soil, under stones and logs or in dead wood, under loose bark, in cavities of plants or in plant galls, under leaves and rubbish piles and even bird nests. The site of the nest is changed often. Nests are populous with size varying with age (from 2,000-10,000 workers) and contain multiple queens. Brood is found in nests from April until September. Reproductives are found in nests from May until October, flights occur in June and July. This species forages singly from trails and are active during both day and night. They tend Homoptera and feed on dead insects or the juices of decaying fruits and vegetables. It is strongly attracted to sweet substances. It is a common house-infesting ant. (Mackay and Mackay 2002)

| At a Glance | • Supercolonies • Facultatively polygynous • Limited invasive |

Photo Gallery

Identification

A small Dolichoderine that has only the slightest of petiolar nodes and an unusual arrangement of its gastral segments. Unlike other species in this subfamily the final segment of the gaster is directed downward. This leads to the anal pore opening being located ventrally (click on the image below to see details of this character) as opposed to opening at the distal end of the gaster.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 62.833° to 18.956167°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: Canada, United States (type locality).

Neotropical Region: Mexico.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

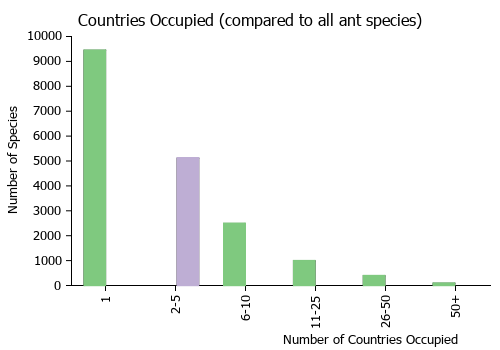

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Biology

Tapinoma sessile is one of the most widespread North American ant species. It is abundant in a wide range of habitats. It nests in the ground, under and within objects, in downed wood and will, in some cases, move into human structures.

The small dark colored workers move about quickly during warm days but they will also forage during cooler temperatures that many other co-occurring ants avoid. When disturbed the highly excitable workers will swarm out of their nest and emit a distinctive pheromone.

Nests of this species can contain thousands of workers and many queens. Workers tend Homoptera and will opportunistically forage on a wide variety of items, being especially attracted to liquid exudates that are rich in carbohydrates. M.R. Smith (1965), reporting on eastern U.S. pest ants, provides this description of their biology: This common and widely distributed ant is one of our most adaptable species, occurring from sea level to 10,500 feet. It nests in a wide variety of habitats, ranging from sandy beaches, pastures, open fields, woodlands, and bogs, to houses. Most nests in the soil are beneath objects such as stones or logs, but this versatile species also nests under the bark of logs and stumps, in plant cavities, insect galls, refuse, piles, and bird and mammal nests. Nests in the soil are indefinite in form, shallow, and of little permanency. The colonies range in size from a few hundred individuals to many thousands, and contain numerous reproductive females. The individuals of the various colonies are not antagonistic to each other, but are hostile to the introduced Argentine ant. Mating takes place in the nest between males and their sister females, but nuptial flights have also been observed. Although females have been observed to establish colonies independently, it is also highly possible that the ants may form new colonies when one or more fertile females leave the parental colony accompanied by a number of workers. Workers are active and rapid, and normally travel in files. When alarmed, the workers dash around excitedly in an erratic manner, quite often with the posterior part of their abdomen elevated. Workers also emit from theip abdominal glands an odor which has been likened to that of rotten coconut. In Mississippi, male pupae have been noted from April 16 to 30, and males and winged females from May 1 to 15. In Bogs in southeastern Michigan, Kannowski has observed nuptial flights from Jime 26 to July 15. Few ants exceed sessile in their love for honeydew. Not only do workers eat honeydew avidly, but they assiduously attend such honeydew-excreting insects as plant lice, scale insects, mealybugs, and membracids. In some instances, workers have been observed transporting live plant lice. When mealybugs have been disturbed by collectors, the worker ants have tried to pick them up and carry them away. Workers visit the floral and extrafloral nectaries of plants in search of their glandular secretions. Like many species of ants, the workers feed on both dead and live insects.

T. sessile, one of our more important house infesting ants, is capable of invading houses from outdoors, or nesting inside. Although the ants feed on a wide variety of household foods, such as raw and cooked meats, cooked vegetables, dairy products, fruit juices, and pastries, they appear to show a preference for sweets.

Hamm (2010) - Smith’s descriptions were based on specimens from Illinois, from which he reported all colonies as polygynous, with colony size varying from 100 to 10,000 workers. All colonies Smith examined were house infesting, and he did not report collecting ants from natural habitats. There may be a trend within the Dolichoderinae, species that are normally monogynous in their native habitat become polygynous and greatly increase the number of workers when the colony becomes invasive or pestiferous (Giraud et al. 2002, Ingram 2002).

Nests of T. sessile were found by Gibson et al. (2019) in bird nests.

Foraging

VanWeelden et al. (2015) found that food was quickly and thoroughly distributed through a colony when food was located close to the nest. In polydomous colonies food was relatively well distributed within parts of the colony found close to the food source and was less efficiently spread to individuals in more distant nests.

Colongy Founding

Nests are founded by independently, by single queens, and dependently, via fission or budding (Kimball 2016b).

Regional Notes

Colorado

Kimball (2016a) - Nests of T. sessile were observed at 9 of the 14 geographic locations. Over the observation periods, temperature ranged from 13.3 to 26.1° Celsius. Forty-four of the approximately 990 rocks examined (4.5%) were found to shelter T. sessile workers and brood. Of the 44 rocks under which T. sessile nests were found, 16 (36.4%) distributed over 8 geographic sites contained visible queens. Only 4 of these 16 nests (25%) were observed to be polygynous. The other 12 (75%) contained only a single visible queen, suggesting monogyny. Observed queen number for each of the four polygynous nests was 2, 2, 5, and 3. These were distributed over three separate sites, all located at higher elevations (2,146 to 2,896 meters). Two of the sites were montane, while one was subalpine. The data show a surprisingly low variation in queen number, when compared to earlier literature from other states (e.g., Smith, 1928; Buczkowski, 2010), as well as an apparent tendency towards monogyny.

Apparent plesiobiosis was also found with some frequency. It was observed in 7 of the 44 nests (15.9% of total observed nests), distributed over three separate sites. Three of these nesting associations were with Solenopsis molesta although these could have been instances of lestobiosis (covert thievery by neighboring ant colonies), given that S. molesta is a well-known brood thief (Holldobler and Wilson, 1990). Three other observed associations were with Lasius species and one was with a Myrmica species. In at least one of these cases (a compound nest between T. sessile and a Lasius sp.), workers of the two species intermingled freely and without aggression or avoidance. In fact, at first glance, they appeared to make up a single colony. Throughout the study, plesiobiosis was found only at elevations of 2057 meters and higher. However, the author has made several informal observations of plesiobiosis in T. sessile at significantly lower elevations during prior years.

One apparent behavioral association deserves special note. On June 1, 2014, at Comanche Reservoir, a rock was lifted and found to shelter a nest of an unidentified Lasius species. Within the exposed galleries, a single T. sessile dealate queen wandered slowly amongst the Lasius workers, eventually disappearing down a tunnel and deeper into the nest. Over this period of time, no aggression or avoidance towards the T. sessile queen was seen to take place. This situation is made stranger by the fact that the queen was alone, without workers of her own, potentially suggesting a parasitic (e.g., xenobiotic) relationship (Buschinger, 2009). Even if a T. sessile nest had been located beneath that of the Lasius, this would have implied an extraordinarily fused nesting arrangement between the two species. Multiple undescribed inquilines of T. sessile have been mentioned in the literature (Fisher and Cover, 2007; Ellison et ai., 2012). However, these have only been reported to parasitize T. sessile, not ants from other genera and subfamilies. Also, the queen observed here did not show the characteristically small size of at least one of these inquiline species (Ellison et al., 2012).

Seven of the T. sessile sampled nests were observed to contain alate reproductives (male or female), distributed over only three geographic locations. When considering colony life cycle, it is important to note that these particular sites were investigated from late-June to mid-July. However, no flight activity was observed.

The data suggest that both polygyny and monogyny are present in northcentral Colorado populations, apparently intermixed. Polygyny was more common at higher (i.e., montane and subalpine) elevations. This could be explained by higher mortality of solitary founding queens when faced with the colder and harsher conditions of higher altitudes (e.g., Heinze, 1992). Colder environments might thus favor young queens that remain in their natal nest rather than disperse, giving rise to polygyny. The study also shows a relatively high occurrence of plesiobiosis in local T. sessile, including associations with multiple other ant species. This could be an adaptation to scarce nesting sites (Czechowski, 2004), but it is difficult to speculate without further study. Finally, also included is a single observation that could indicate socially parasitic (e.g., xenobiotic) behavior in T. sessile. Intriguingly, despite several years of informal searching, the author has never seen T. sessile in Colorado urban or suburban areas and parks. This contrasts with earlier findings that present T. sessile as a successful and abundant pest in human modified habitats (e.g., Smith, 1928; Buczkowski, 2010).

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a host for the Microdon fly Microdon globosus (a predator) in Florida, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin (Fabricius, 1805).

- This species is a host for the cricket Myrmecophilus pergandei (a myrmecophile) in United States.

- This species is a host for the cestode Mesocestoides sp. (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode secondary; indirect transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is associated with the following aphids: Aphis asclepiadis, Aphis gossypii, Aphis helianthi, Aphis lugentis, Aphis salicariae, Aphis varians, Bipersona torticauda, Brachycaudus cardui, Chaitophorus populicola, Chaitophorus populifolii, Chaitophorus viminalis, Cinara atlantica, Cinara pineti, Cinara ponderosae, Dysaphis sorbi and Myzus persicae (Siddiqui et al., 2019, and included references).

Flight Period

| X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info.

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

- Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Life History Traits

- Queen number: polygynous (Holldobler & Wilson, 1977)

Castes

Worker

| |

| . | |

Queen

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0104849. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0104850. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Male

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0104534. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- sessile. Formica sessilis Say, 1836: 287 (w.q.) U.S.A. Emery, 1895c: 333 (q.m.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1951: 196 (l.); Crozier, 1970: 119 (k.); Taber & Cokendolpher, 1988: 95 (k.). Combination in Tapinoma: Smith, F. 1858b: 57. Senior synonym of parva, boreale Roger (and its junior synonym boreale Provancher): Mayr, 1886d: 434; Creighton, 1950a: 353; of gracilis: Emery, 1895c: 337; Wheeler, W.M. 1902f: 20; Creighton, 1950a: 353; of dimmocki: Shattuck, 1992c: 153. See also: Smith, M.R. 1928a: 307; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1422; Kupyanskaya, 1990: 156; Shattuck, 1994: 153; Hamm, 2010: 24.

- boreale. Tapinoma boreale Roger, 1863a: 165 (w.q.) NORTH AMERICA. Subspecies of sessile: Dalla Torre, 1893: 164; Ruzsky, 1925b: 45; Ruzsky, 1936: 95. Senior synonym of boreale Provancher: Dalla Torre, 1893: 164. Junior synonym of sessile: Mayr, 1886d: 434; Creighton, 1950a: 353. [Note. Many publications refer to T. boreale Mayr, 1886d: 434, for example Creighton, 1950a: 342. This reference is to T. boreale Roger as redescribed by Mayr; there is no T. boreale Mayr.]

- gracilis. Formica gracilis Buckley, 1866: 158 (w.q.) U.S.A. [Unresolved junior primary homonym of Formica gracilis Fabricius, 1804: 405 (now in Pseudomyrmex).] Junior synonym of sessile: Emery, 1895c: 337; Wheeler, W.M. 1902f: 20.

- parva. Formica parva Buckley, 1866: 159 (w.) U.S.A. Junior synonym of sessile: Mayr, 1886d: 434.

- boreale. Tapinoma boreale Provancher, 1887: 238 (w.q.) CANADA. Junior primary homonym and junior synonym of boreale Roger: Dalla Torre, 1893: 164.

- dimmocki. Bothriomyrmex dimmocki Wheeler, W.M. 1915b: 417 (w.q.) U.S.A. Combination in Tapinoma: Emery, 1925e: 19. Junior synonym of sessile: Shattuck, 1992c: 153.

Type Material

Neotype. Worker, with the following measurements (see Table 2 for full character deÞnitions): HL, 0.68 mm; HW, 0.60 mm; SL, 0.60 mm; EL, 0.18 mm; MFC, 0.18 mm; EW, 0.14 mm; FL, 0.50 mm; LHL, 0.40 mm; PW, 0.42 mm; ES, 2.52 mm; SI, 88.2; and CI, 88.20. The neotype resides in the collection of the Museum of Comparative Zoology (Museum of Comparative Zoology) at Harvard University and bears the following labels: “USA Posey Co. New Harmony, IN 21-VI-09, 110 m 38.130_ N, 87.935_ W Coll by: C. A. Hamm” “Nest in soil next to house 5 m from grave of T. Say”

This concolored black specimen does not differ in any significant way from the escriptions of Say (1836) and Shattuck (1992, 1995). This specimen will carry a label designating it as the neotype. Additional material collected from this series has been deposited at the University of California, Davis, MCZ, MSUC, and Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Taxonomic Notes

Hamm (2010) - After being originally described as Formica sessilis, in the Boston Journal of Natural History by Thomas Say in 1836, there has been little taxonomic work on T. sessile apart from its status as a pest. The original description is one paragraph in length and does not adequately describe a taxon that is highly variable in both size and color. The original species description was based on workers and queens from Indiana and many of the specimens from his collection have been lost, including the holotype (Say 1836; R. R. Snelling, personal communication).

In 1928, M. R. Smith revisited the biology of T. sessile. He provided a more complete description of T. sessile and provided measurement data and descriptions of color variation to demonstrate the level of phenotypic variability present in this species. The focus of Smith’s work was related to T. sessile’s ability to infest houses (hence its common name the odorous house ant); as such, his scope was limited. He did not mention any bicolored morphs (Smith 1928).

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Hamm (2010):

Worker

(n = 427). HL, 0.68 ±0.06 mm; HW,0.63 ± 0.08 mm; SL, 0.64 ± 0.07 mm; EL, 0.17 ± 0.02 mm; MFC, 0.22 ± 0.03 mm; EW, 0.14 ± 0.02 mm; FL, 0.53 ± 0.09 mm; LHL, 0.46 ± 0.08 mm; PW, 0.43 ± 0.05 mm; ES, 2.33 ± 0.47 mm; SI, 93 ± 3.58; and CI, 91.5 ± 4.39.

Queen

(n = 64). HL, 0.80 ± 0.05 mm; HW, 0.85 ± 0.05 mm; SL, 0.73 ± 0.06 mm; EL, 0.26 ± 0.02 mm; MFC, 0.28 ± 0.04 mm; EW, 0.21 ± 0.02 mm; FL, 0.72 ± 0.08 mm; LHL, 0.61 ± 0.08 mm; PW, 0.83 ± 0.06 mm; WL, 1.17 ± 0.09 mm; WGL, 3.52 ± 0.52 mm; ES, 5.54 ± 1.04 mm; SI, 91.8 ± 5.56; CI, 106 ± 3.18.

Male

(n =59). HL, 0.71 ± 0.05mm; HW, 0.73 ± 0.06 mm; SL, 0.69 ± 0.06 mm; EL, 0.29 ± 0.02 mm; MFC, 0.22 ± 0.02 mm; EW, 0.34 ± 0.02 mm; FL, 0.76 ± 0.07 mm; LHL, 0.65 ± 0.06 mm; PW, 0.75 ± 0.07 mm; MML, 1.09 ± 0.10 mm; WGL, 3.35 ± 0.31 mm; ES, 6.98 ± 1.04 mm; SI, 96.4 ± 4.81; and CI, 103 ± 2.62.

Karyotype

- n = 8, 2n = 16, karyotype = 14M+2A (USA) (Crozier, 1970a; Taber & Cokendolpher, 1988).

Etymology

Descriptive. sessile translates as "sitting" and this is presumably in reference to the gaster sitting directly on top of the petiole.

References

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Atchison, R. A., Lucky, A. 2022. Diversity and resilience of seed-removing ant species in Longleaf Sandhill to frequent fire. Diversity 14, 1012 (doi:10.3390/d14121012).

- Booher, D.B. 2021. The ant genus Strumigenys Smith, 1860 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in western North America north of Mexico. Zootaxa 5061, 201–248 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5061.2.1).

- Borowiec, M.L., Moreau, C.S., Rabeling, C. 2020. Ants: Phylogeny and Classification. In: C. Starr (ed.), Encyclopedia of Social Insects (doi:10.1007/978-3-319-90306-4_155-1).

- Boucher, P., Hébert, C., Francoeur, A., Sirois, L. 2015. Postfire succession of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) nesting in dead wood of Northern Boreal Forest. Environmental Entomology 44, 1316–1327 (doi:10.1093/ee/nvv109).

- Buczkowski, G. & Krushelnycky, P. 2012. The odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), as a new temperate-origin invader. Myrmecological News 16:61-66.

- Buczkowski, G. 2010. Extreme life history plasticity and the evolution of invasive characteristics in a native ant. Biological Invasions 12:3343–3349 (doi:10.1007/s10530-010-9727-6).

- Buczkowski, G., Bennett, G. 2008. Seasonal polydomy in a polygynous supercolony of the odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile. Ecol Entomol 33:780–788 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2008.01034.x).

- Cantone S. 2018. Winged Ants, The queen. Dichotomous key to genera of winged female ants in the World. The Wings of Ants: morphological and systematic relationships (self-published).

- Carroll, T.M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). M.S. thesis, Purdue University.

- Chick, L.D., Lessard, J.-P., Dunn, R.R., Sanders, N.J. 2020. The coupled influence of thermal physiology and biotic interactions on the distribution and density of ant species along an elevational gradient. Diversity 12, 456 (doi:10.3390/d12120456).

- Cordonnier, M., Blight, O., Angulo, E., Courchamp, F. 2020. Behavioral data and analyses of competitive interactions between invasive and native ant species. Animals 10, 2451 (doi:10.3390/ani10122451).

- Creighton, W. S. 1950a. The ants of North America. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 104: 1-585 (page 353, Senior synonym of gracilis, parva and boreale Roger (and its junior synonym borale Provancher))

- Crozier, R. H. 1970a. Karyotypes of twenty-one ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with reviews of the known ant karyotypes. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 12: 109-128 (page 119, karyotype described)

- Davis, T. 2009. The ants of South Carolina (thesis, Clemson University).

- Deyrup, M.A., Carlin, N., Trager, J., Umphrey, G. 1988. A review of the ants of the Florida Keys. Florida Entomologist 71: 163-176.

- Emery, C. 1895d. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. (Schluss). Zool. Jahrb. Abt. Syst. Geogr. Biol. Tiere 8: 257-360 (page 333, queen, male described; page 337, Senior synonym of gracilis)

- Fairweather, A.D., Lewis, J.H., Hunt, L., Smith, M.A., McAlpine, D.F. 2020. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Rockwood Park, New Brunswick: An assessment of species richness and habitat. Northwestern Naturalist 27(3):576–584.

- Fournier, D., Tindo, M., Kenne, M., Mbenoun Masse, P.S., Van Bossche, V., De Coninck, E., Aron, S. 2012. Genetic structure, nestmate recognition and behaviour of two cryptic species of the invasive Big-Headed Ant Pheidole megacephala. PLoS ONE 7(2): e31480 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031480).

- Gibson, J. C., A. V. Suarez, D. Qazi, T. J. Benson, S. J. Chiavacci, and L. Merrill. 2019. Prevalence and consequences of ants and other arthropods in active nests of Midwestern birds. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 97:696-704. doi:10.1139/cjz-2018-0182

- Hamm, C.A. 2010. Multivariate discrimination and description of a new species of Tapinoma from the western United States. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 103:20-29.

- Higgins, R.J., Lindgren, B.S. 2012. An evaluation of methods for sampling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in British Columbia, Canada. The Canadian Entomologist 144, 491–507 (doi:10.4039/tce.2012.50).

- Hoey-Chamberlain, R., Rust, M.K., Klotz, J.H. 2013. A review of the biology, ecology and behavior of Velvety Tree Ants of North America. Sociobiology 60(1): 1-10.

- Hoey-Chamberlain, R.V. 2012. Food preference, survivorship, and intraspecific interactions of Velvety Tree Ants. M.S. thesis, University of California, Riverside.

- Ipser, R.M., Brinkman, M.A., Gardner, W.A., Peeler, H.B. 2004. A survey of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Georgia. Florida Entomologist 87: 253-260.

- Ivanov, K. 2019. The ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): an updated checklist. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 70: 65–87 (doi:10.3897@jhr.70.35207).

- Kimball, C. P. 2016a. Colony Structure in Tapinoma sessile Ants of Northcentral Colorado: A Research Note. Entomological News. 125:357-362. doi:10.3157/021.125.0507

- Kimball, C. P. 2016b. Independent Colony Foundation in Tapinoma sessile of Northcentral Colorado. Entomological News. 126:83-86. doi:10.3157/021.126.0203

- Kupyanskaya, A. N. 1990a. Ants of the Far Eastern USSR. Vladivostok: Akademiya Nauk SSSR, 258 pp. (page 156, see also)

- MacGown, J.A., Booher, D., Richter, H., Wetterer, J.K., Hill, J.G. 2021. An updated list of ants of Alabama (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with new state records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 147: 961-981 (doi:10.3157/061.147.0409).

- Mackay, W. P. and E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, NY.

- Mayr, G. 1886d. Die Formiciden der Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 36: 419-464 (page 434, Senior synonym of parva and boreale Roge (and its junior synonym borale Provancher))

- Moss, A.D., Swallow, J.G., Greene, M.J. 2022. Always under foot: Tetramorium immigrans (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), a review. Myrmecological News 32: 75-92 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_032:075).

- Moura, M.N., Cardoso, D.C., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. The tight genome size of ants: diversity and evolution under ancestral state reconstruction and base composition. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa135 (doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa135).

- Oswalt, D.A. 2007. Nesting and foraging characteristics of the black carpenter ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus DeGeer (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ph.D. thesis, Clemson University.

- Penick, C.A., Smith, A.A. 2015. The true odor of the Odorous House Ant. American Entomologist 61, 85-87.

- Rericha, L. 2007. Ants of Indiana. Indiana Department of Natural Resources, 51pp.

- Say, T. 1836. Descriptions of new species of North American Hymenoptera, and observations on some already described. Boston J. Nat. Hist. 1: 209-305 (page 287, worker, queen described)

- Shattuck, S. O. 1992c. Generic revision of the ant subfamily Dolichoderinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 21: 1-181 (page 153, Senior synonym of dimmocki)

- Shattuck, S. O. 1994. Taxonomic catalog of the ant subfamilies Aneuretinae and Dolichoderinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Univ. Calif. Publ. Entomol. 112:i-xix, 1-241. (page 153, see also)

- Siddiqui, J. A., Li, J., Zou, X., Bodlah, I., Huang, X. 2019. Meta-analysis of the global diversity and spatial patterns of aphid-ant mutualistic relationships. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 17: 5471-5524 (doi:10.15666/aeer/1703_54715524).

- Smith, D. R. 1979. Superfamily Formicoidea. Pp. 1323-1467 in: Krombein, K. V., Hurd, P. D., Smith, D. R., Burks, B. D. (eds.) Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Apocrita (Aculeata). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Pr (page 1422, see also)

- Smith, F. 1858b. Catalogue of hymenopterous insects in the collection of the British Museum. Part VI. Formicidae. London: British Museum, 216 pp. (page 57, Combination in Tapinoma)

- Smith, M. R. 1928a. The biology of Tapinoma sessile Say, an important house-infesting ant. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 21: 307-330 (page 307, see also)

- Stukalyuk, S., Radchenko, A., Akhmedov, A., Reshetov, A., Netsvetov, M. 2021. Acquisition of invasive traits in ant, Crematogaster subdentata Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in urban environments. Serangga 26: 1-29.

- Taber, S. W.; Cokendolpher, J. C. 1988. Karyotypes of a dozen ant species from the southwestern U.S.A. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Caryologia 41: 93-102 (page 95, karyotype described)

- Tseng, S.-P. 2020. Evolutionary history of a global invasive ant, Paratrechina longicornis (Dissertation_全文 ). Ph.D. thesis, Kyoto University.

- Tseng, S.-P., Hsu, P.-W., Lee, C.-C., Wetterer, J.K., Hugel, S., Wu, L.-H., Lee, C.-Y., Yoshimura, T., Yang, C.-C.S. 2020. Evidence for common horizontal transmission of Wolbachia among ants and ant crickets: Kleptoparasitism added to the list. Microorganisms 8, 805. (doi:10.3390/MICROORGANISMS8060805).

- VanWeelden, M. T., G. Bennett, and G. Buczkowski. 2015. The Effects of Colony Structure and Resource Abundance on Food Dispersal in Tapinoma sessile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of Insect Science. 15. doi:10.1093/jisesa/ieu176

- Varela-Hernández, F., Medel-Zosayas, B., Martínez-Luque, E.O., Jones, R.W., De la Mora, A. 2020. Biodiversity in central Mexico: Assessment of ants in a convergent region. Southwestern Entomologist 454: 673-686.

- Waters, J.S., Keough, N.W., Burt, J., Eckel, J.D., Hutchinson, T., Ewanchuk, J., Rock, M., Markert, J.A., Axen, H.J., Gregg, D. 2022. Survey of ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in the city of Providence (Rhode Island, United States) and a new northern-most record for Brachyponera chinensis (Emery, 1895). Check List 18(6), 1347–1368 (doi:10.15560/18.6.1347).

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1951. The ant larvae of the subfamily Dolichoderinae. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 53: 169-210 (page 196, larva described)

- Wheeler, W. M. 1902g. A consideration of S. B. Buckley's "North American Formicidae.". Trans. Tex. Acad. Sci. 4: 17-31 (page 20, Senior synonym of gracilis)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Addison D. S., I. Bartoszek, V. Booher, M. A. Deyrup, M. Schuman, J. Schmid, and K. Worley. 2016. Baseline surveys for ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the western Everglades, Collier County, Florida. Florida Entomologist 99(3): 389-394.

- Albrecht M. 1995. New Species Distributions of Ants in Oklahoma, including a South American Invader. Proc. Okla. Acad. Sci. 75: 21-24.

- Allred D. M. 1982. Ants of Utah. The Great Basin Naturalist 42: 415-511.

- Allred, D.M. 1982. The ants of Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 42:415-511.

- Amstutz M. E. 1943. The ants of the Kildeer plain area of Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). The Ohio Journal of Science 43(4): 165-173.

- Annotated Ant Species List Ordway-Swisher Biological Station. Downloaded at http://ordway-swisher.ufl.edu/species/os-hymenoptera.htm on 5th Oct 2010.

- Antonov I. A., and A. S. Pleshanov. 2011. Ecological-geographical features of Myrmicafauna of Baikal Region. Bulletin of the Buryat State. Univ. 4: 104-108.

- Backlin, Adam R., Sara L. Compton, Zsolt B. Kahancza and Robert N. Fisher. 2005. Baseline Biodiversity Survey for Santa Catalina Island. Catalina Island Conservancy. 1-45.

- Banschbach V. S., and E. Ogilvy. 2014. Long-term Impacts of Controlled Burns on the Ant Community (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of a Sandplain Forest in Vermont. Northeastern Naturalist 21(1): 1-12.

- Beck D. E., D. M. Allred, W. J. Despain. 1967. Predaceous-scavenger ants in Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 27: 67-78

- Belcher A. K., M. R. Berenbaum, and A. V. Suarez. 2016. Urbana House Ants 2.0.: revisiting M. R. Smith's 1926 survey of house-infesting ants in central Illinois after 87 years. American Entomologist 62(3): 182-193.

- Bestelmeyer B. T., and J. A. Wiens. 2001. Local and regional-scale responses of ant diversity to a semiarid biome transition. Ecography 24: 381-392.

- Blacker, N.C. 1992. Some Ants from Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. J. Entomol. Soc. Bri. Columbia 89:3-12.

- Blacker, N.C. 1992. Some ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 89:3-12

- Blades, D.C.A. and S.A. Marshall. Terrestrial arthropods of Canadian Peatlands: Synopsis of pan trap collections at four southern Ontario peatlands. Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada 169:221-284

- Borchert, H.F. and N.L. Anderson. 1973. The Ants of the Bearpaw Mountains of Montana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 46(2):200-224

- Boucher P., C. Hebert, A. Francoeur, and L. Sirois. 2015. Postfire succession of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) nesting in dead wood of northern boreal forest. Environ. Entomol. 44(5): 1316-1327: DOI: 10.1093/ee/nvv109

- Boulton A. M., Davies K. F. and Ward P. S. 2005. Species richness, abundance, and composition of ground-dwelling ants in northern California grasslands: role of plants, soil, and grazing. Environmental Entomology 34: 96-104

- Buczkowski, G. and G. Bennett. 2009. The influence of forager number and colony size on food distribution in the odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile. Insectes Sociaux 56(2): 185-192.

- Buren W. F. 1944. A list of Iowa ants. Iowa State College Journal of Science 18:277-312

- Callcott A. M. A., D. H. oi, H. L. Collins, D. F. Williams, and T. C. Lockley. 2000. Seasonal Studies of an Isolated Red Imported Fire Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Population in Eastern Tennessee. Environmental Entomology, 29(4): 788-794.

- Campbell J. W., S. M. Grodsky, D. A. Halbritter, P. A. Vigueira, C. C. Vigueira, O. Keller, and C. H. Greenberg. 2019. Asian needle ant (Brachyponera chinensis) and woodland ant responses to repeated applications of fuel reduction methods. Ecosphere 10(1): e02547.

- Campbell K. U., and T. O. Crist. 2017. Ant species assembly in constructed grasslands isstructured at patch and landscape levels. Insect Conservation and Diversity doi: 10.1111/icad.12215

- Canadensys Database. Dowloaded on 5th February 2014 at http://www.canadensys.net/

- Carroll T. M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Master's Thesis Purdue university, 385 pages.

- Choate B., and F. A. Drummond. 2012. Ant Diversity and Distribution (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Throughout Maine Lowbush Blueberry Fields in Hancock and Washington Counties. Environ. Entomol. 41(2): 222-232.

- Choate B., and F. A. Drummond. 2013. The influence of insecticides and vegetation in structuring Formica Mound ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Maine lowbush blueberry. Environ. Entomol. 41(2): 222-232.

- Clark Adam. Personal communication on November 25th 2013.

- Clarke K.M., Fisher B.L. and LeBuhn G. 2008. The influece of urban park characteristics on ant (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) communities. Urban Ecosyst 11: 317-334

- Cokendolpher J. C., and O. F. Francke. 1990. The ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of western Texas. Part II. Subfamilies Ecitoninae, Ponerinae, Pseudomyrmecinae, Dolichoderinae, and Formicinae. Special Publications, the Museum. Texas Tech University 30:1-76.

- Colby, D. and D. Prowell. 2006. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Wet Longleaf Pine Savannas in Louisiana. Florida Entomologist 89(2):266-269

- Cole A. C. 1940. A Guide to the Ants of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee. American Midland Naturalist 24(1): 1-88.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1936. An annotated list of the ants of Idaho (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Canadian Entomologist 68: 34-39.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1937. An annotated list of the ants of Arizona (Hym.: Formicidae). [concl.]. Entomological News 48: 134-140.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1942. The ants of Utah. American Midland Naturalist 28: 358-388.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1949. The ants of Mountain Lake, Virginia. Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science 24: 155-156.

- Cole, A.C. 1936. An annotated list of the ants of Idaho (Hymenoptera; Formicidae). Canadian Entomologist 68(2):34-39

- Coovert G. A. 2005. The Ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ohio Biological Survey, Inc. 15(2): 1-207.

- Coovert, G.A. 2005. The Ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Ohio Biological Survey Bulletin New Series Volume 15(2):1-196

- Cover S. P., and R. A. Johnson. 20011. Checklist of Arizona Ants. Downloaded on January 7th at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/AZants-2011%20updatev2.pdf

- Dash S. T. and L. M. Hooper-Bui. 2008. Species diversity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Louisiana. Conservation Biology and Biodiversity. 101: 1056-1066

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Davidson, D.W., S.C. Cook and R. R. Snelling. 2004. Liquid-feeding performances of ants (Formicidae): ecological and evolutionary implications. Oecologia 139: 255266.

- Davis W. T., and J. Bequaert. 1922. An annoted list of the ants of Staten Island and Long Island, N. Y. Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological Society 17(1): 1-25.

- Del Toro I., K. Towle, D. N. Morrison, and S. L. Pelini. 2013. Community Structure, Ecological and Behavioral Traits of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Massachusetts Open and Forested Habitats. Northeastern Naturalist 20: 1-12.

- Del Toro, I. 2010. PERSONAL COMMUNICATION. MUSEUM RECORDS COLLATED BY ISRAEL DEL TORO

- Des Lauriers J., and D. Ikeda. 2017. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the San Gabriel Mountains of Southern California, USA with an annotated list. In: Reynolds R. E. (Ed.) Desert Studies Symposium. California State University Desert Studies Consortium, 342 pp. Pages 264-277.

- Deyrup M., C. Johnson, G. C. Wheeler, J. Wheeler. 1989. A preliminary list of the ants of Florida. Florida Entomologist 72: 91-101

- Downing H., and J. Clark. 2018. Ant biodiversity in the Northern Black Hills, South Dakota (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 91(2): 119-132.

- Drummond F. A., A. M. llison, E. Groden, and G. D. Ouellette. 2012. The ants (Formicidae). In Biodiversity of the Schoodic Peninsula: Results of the Insect and Arachnid Bioblitzes at the Schoodic District of Acadia National Park, Maine. Maine Agricultural and forest experiment station, The University of Maine, Technical Bulletin 206. 217 pages

- DuBois M. B. 1981. New records of ants in Kansas, III. State Biological Survey of Kansas. Technical Publications 10: 32-44

- DuBois M. B. 1994. Checklist of Kansas ants. The Kansas School Naturalist 40: 3-16

- Dubois, M.B. and W.E. Laberge. 1988. An Annotated list of the ants of Illionois. pages 133-156 in Advances in Myrmecology, J. Trager

- Ellison A. M. 2012. The Ants of Nantucket: Unexpectedly High Biodiversity in an Anthropogenic Landscape. Northeastern Naturalist 19(1): 43-66.

- Ellison A. M., E. J. Farnsworth, and N. J. Gotelli. 2002. Ant diversity in pitcher-plant bogs of Massachussetts. Northeastern Naturalist 9(3): 267-284.

- Ellison A. M., S. Record, A. Arguello, and N. J. Gotelli. 2007. Rapid Inventory of the Ant Assemblage in a Temperate Hardwood Forest: Species Composition and Assessment of Sampling Methods. Environ. Entomol. 36(4): 766-775.

- Ellison A. M., and E. J. Farnsworth. 2014. Targeted sampling increases knowledge and improves estimates of ant species richness in Rhode Island. Northeastern Naturalist 21(1): NENHC-13NENHC-24.

- Epperson, D.M. and C.R. Allen. 2010. Red Imported Fire Ant Impacts on Upland Arthropods in Southern Mississippi. American Midland Naturalist, 163(1):54-63.

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Fisher B. L. 1997. A comparison of ant assemblages (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) on serpentine and non-serpentine soils in northern California. Insectes Sociaux 44: 23-33

- Forster J.A. 2005. The Ants (hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Alabama. Master of Science, Auburn University. 242 pages.

- Francoeur A. 1997. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Yukon. Biological Survey of Canada Monograph Series 2: 901-910.

- Francoeur A., and R. R. Snelling. 1979. Notes for a revision of the ant genus Formica. 2. Reidentifications for some specimens from the T. W. Cook collection and new distribution data (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Contr. Sci. (Los Angel.) 309: 1-7.

- Francoeur, A. 1997. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Yukon. Pages 901 910 in H.V. Danks and J.A. Downes (Eds.), Insects of the Yukon. Biological Survey of Canada (Terrestrial Arthropods), Ottawa.

- Frye J. A., T. Frye, and T. W. Suman. 2014. The ant fauna of inland sand dune communities in Worcester County, Maryland. Northeastern Naturalist, 21(3): 446-471.

- General D. M., and L. C. Thompson. 2011. New Distributional Records of Ants in Arkansas for 2009 and 2010 with Comments on Previous Records. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 65: 166-168.

- General D., and L. Thompson. 2008. Ants of Arkansas Post National Memorial: How and Where Collected. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 62: 52-60.

- General D.M. & Thompson L.C. 2007. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Arkansas Post National Memorial. Journal of the Arkansas Acaedemy of Science. 61: 59-64

- General D.M. & Thompson L.C. 2008. New Distributional Records of Ants in Arkansas for 2008. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science. 63: 182-184

- Glasier J. R. N., J. H. Acorn, S. E. Nielsen, and H. Proctor. 2013. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Alberta: A key to species based primarily on the worker caste. Canadian Journal of Arthropod Identification 22: 1-104.

- Glasier J. R. N., S. E. Nielsen, J. Acorn, and J. Pinzon. 2019. Boreal sand hills are areas of high diversity for Boreal ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Diversity 11, 22; doi:10.3390/d11020022.

- Gotelli, N.J. and A.M. Ellison. 2002. Biogeography at a Regional Scale: Determinants of Ant Species Density in New England Bogs and Forests. Ecology 83(6):1604-1609

- Greenberg L., M. Martinez, A. Tilzer, K. Nelson, S. Koening, and R. Cummings. 2015. Comparison of different protocols for control of the Red Imported Fire Ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), in Orange County, California, including a list of co-occurring ants. Southwestern Entomologist 40(2): 297-305.

- Gregg, R.T. 1963. The Ants of Colorado.

- Guénard B., K. A. Mccaffrey, A. Lucky, and R. R. Dunn. 2012. Ants of North Carolina: an updated list (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 3552: 1-36.

- Guénard B., and R. R. Dunn. 2012. A checklist of the ants of China. Zootaxa 3558: 1-77.

- Hamm C. A. 2010. Multivariate discrimination and description of a new species of Tapinoma from the western United States. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 103: 20-29

- Headley A. E. 1943. The ants of Ashtabula County, Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). The Ohio Journal of Science 43(1): 22-31.

- Heithaus R. E., and M. Humes. 2003. Variation in Communities of Seed-Dispersing Ants in Habitats with Different Disturbance in Knox County, Ohio. OHIO J. SCI. 103 (4): 89-97.

- Herbers J. M. 2011. Nineteen years of field data on ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): what can we learn. Myrmecological News 15: 43-52.

- Herbers J. N. 1989. Community structure in north temperate ants: temporal and spatial variation. Oecologia 81: 201-211.

- Higgins J. W., N. S. Cobb, S. Sommer, R. J. Delph, and S. L. Brantley. 2014. Ground-dwelling arthropod responses to succession in a pinyon-juniper woodland. Ecosphere 5(1):5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ES13-00270.1

- Hill J.G. & Brown R. L. 2010. The Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Fauna of Black Belt Prairie Remnants in Alabama and Mississippi. Southeastern Naturalist. 9: 73-84

- Hoey-Chamberlain R. V., L. D. Hansen, J. H. Klotz and C. McNeeley. 2010. A survey of the ants of Washington and Surrounding areas in Idaho and Oregon focusing on disturbed sites (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology. 56: 195-207

- Holway D.A. 1998. Effect of Argentine ant invasions on ground-dwelling arthropods in northern California riparian woodlands. Oecologia. 116: 252-258

- Honda J., B. Robinson, M. Valainis, R. Vetter, and J. Jahncke. 2017. Southeast Farallon Island arthropod survey. Insecta Mundi 532: 1-15.

- Hosoichi S., M. M. Rahman, T. Murakami, S. H. Park, Y. Kuboki, and K. Ogata. 2019. Winter activity of ants in an urban area of western Japan. Sociobiology 66(3): 414-419.

- Houdeshell H., R. L. Friedrich, and S. M. Philpott. 2011. Effects of Prescribed Burning on Ant Nesting Ecology in Oak Savannas. The American Midland Naturalist, 166(1): 98-111.

- Ipser R. M. 2004. Native and exotic ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Georgia: Ecological Relationships with implications for development of biologically-based management strategies. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, University of Georgia. 165 pages.

- Ivanov, K. 2019. The ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): an updated checklist. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 70: 65–87.

- Ivanov K., L. Hightower, S. T. Dash, and J. B. Keiper. 2019. 150 years in the making: first comprehensive list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Virginia, USA. Zootaxa 4554 (2): 532–560.

- Jeanne R. J. 1979. A latitudinal gradient in rates of ant predation. Ecology 60(6): 1211-1224.

- Johnson C. 1986. A north Florida ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insecta Mundi 1: 243-246

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Johnson, R.A. and P.S. Ward. 2002. Biogeography and endemism of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Baja California, Mexico: a first overview. Journal of Biogeography 29:10091026/

- Judd, W.W. Insects and spiders from goldenrod galls of Gnorimoschema gallaesolidaginis Riley (Gelechiidae). Canadian Entomologist 96: 987-990

- Kannowski P. B. 1956. The ants of Ramsey County, North Dakota. American Midland Naturalist 56(1): 168-185.

- Kiseleva E. F. 1925. On the ant fauna of the Ussuri region. Izv. Tomsk. Gos. Univ. 75: 73-75.

- Kjar D. 2009. The ant community of a riparian forest in the Dyke Marsh Preserve, Fairfax County, Virginiam and a checklist of Mid-Atlantic Formicidae. Banisteria 33: 3-17.

- Kjar D., and Z. Park. 2016. Increased ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) incidence and richness are associated with alien plant cover in a small mid-Atlantic riparian forest. Myrmecological News 22: 109-117.

- Knowlton G. F. 1970. Ants of Curlew Valley. Proceedings of the Utah Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 47(1): 208-212.

- Kupianskaia A.N. 1990. Murav'I (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) Dal'nego Vostoka SSSR (1989). Vladivostok. 258 pages.

- La Rivers I. 1968. A first listing of the ants of Nevada. Biological Society of Nevada, Occasional Papers 17: 1-12.

- Lattke, J.E. 1990. A new genus of myrmicine ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Venezuela. Entomologica Scandinavica 21:173-178

- Lavigne R., and T. J. Tepedino. 1976. Checklist of the insects in Wyoming. I. Hymenoptera. Agric. Exp. Sta., Univ. Wyoming Res. J. 106: 24-26.

- Letendre M., A. Francoeur, R. Beique, and J.-G. Pilon. 1971. Inventaire des fourmis de la Station de Biologie de l'Universite de Montreal, St-Hippolyte, Quebec (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Le Naturaliste Canadien 98(4): 591-606.

- Lidgren, B.S. and A.M. MacIsaac. 2002. A Preliminary Study of Ant Diversity and of Ant Dependence on Dead Wood in Central Interior British Columbia. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-181.

- Lindgren, B.S. and A.M. MacIsaac. 2002. Ant dependence on dead wood in Central Interior British Columbia. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep.PSW-GTR-181

- Lynch J. F. 1981. Seasonal, successional, and vertical segregation in a Maryland ant community. Oikos 37: 183-198.

- Lynch J. F. 1988. An annotated checklist and key to the species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Chesapeake Bay region. The Maryland Naturalist 31: 61-106

- Lynch J. F., and A. K. Johnson. 1988. Spatial and temporal variation in the abundance and diversity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the soild and litter layers of a Maryland forest. American Midland Naturalist 119(1): 31-44.

- MacGown J. A., J. G. Hill, R. L. Brown, T. L. Schiefer, J. G. Lewis. 2012. Ant diversity at Noxubee National Wildlife Refuge in Oktibbeha, Noxubee, and Winston Counties, Mississippi. Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station Bulletin 1197: 1-30

- MacGown J. A., J. G. Hill, and R. L. Brown. 2010. Native and exotic ant in Mississippi state parks. Proceedings: Imported Fire Ant Conference, Charleston, South Carolina, March 24-26, 2008: 74-80.

- MacGown, J.A and J.A. Forster. 2005. A preliminary list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Alabama, U.S.A. Entomological News 116(2):61-74

- MacGown, J.A. and JV.G. Hill. Ants of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Tennessee and North Carolina).

- MacGown, J.A., J.G. Hill, R.L. Brown and T.L. 2009. Ant Diversity at Noxubee National Wildlife Refuge in Oktibbeha, Noxubee, and Winston Counties, Mississippi Report #2009-01. Schiefer. 2009.

- MacGown. J. 2011. Ants collected during the 25th Annual Cross Expedition at Tims Ford State Park, Franklin County, Tennessee

- MacKay W. P. 1993. Succession of ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on low-level nuclear waste sites in northern New Mexico. Sociobiology 23: 1-11.

- Macgown J. A., S. Y. Wang, J. G. Hill, and R. J. Whitehouse. 2017. A List of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Collected During the 2017 William H. Cross Expedition to the Ouachita Mountains of Arkansas with New State Records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society, 143(4): 735-740.

- Mackay W. P., and E. E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 400 pp.

- Mahon M. B., K. U. Campbell, and T. O. Crist. 2017. Effectiveness of Winkler litter extraction and pitfall traps in sampling ant communities and functional groups in a temperate forest. Environmental Entomology 46(3): 470–479.

- Mallis A. 1941. A list of the ants of California with notes on their habits and distribution. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 40: 61-100.

- Mann W. M. 1911. On some Northwestern ants and their guests. Psyche (Cambridge) 18: 102-109.

- Martelli, M.G., M.M. Ward and Ann M. Fraser. 2004. Ant Diversity Sampling on the Southern Cumberland Plateau: A Comparison of Litter Sifting and Pitfall Trapping. Southeastern Naturalist 3(1): 113-126

- Matsuda T., G. Turschak, C. Brehme, C. Rochester, M. Mitrovich, and R. Fisher. 2011. Effects of Large-Scale Wildfires on Ground Foraging Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Southern California. Environmental Entomology 40(2): 204-216.

- Menke S. B., E. Gaulke, A. Hamel, and N. Vachter. 2015. The effects of restoration age and prescribed burns on grassland ant community structure. Environmental Entomology http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvv110

- Menke S. B., and N. Vachter. 2014. A comparison of the effectiveness of pitfall traps and winkler litter samples for characterization of terrestrial ant (Formicidae) communities in temperate savannas. The Great Lakes Entomologist 47(3-4): 149-165.

- Merle W. W. 1939. An Annotated List of the Ants of Maine (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 50: 161-165

- MontBlanc E. M., J. C. Chambers, and P. F. Brussard. 2007. Variation in ant populations with elevation, tree cover, and fire in a Pinyon-Juniper-dominated watershed. Western North American Naturalist 67(4): 469491.

- Moreau C. S., M. A. Deyrup, and L. R. David Jr. 2014. Ants of the Florida Keys: Species Accounts, Biogeography, and Conservation (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Insect Sci. 14(295): DOI: 10.1093/jisesa/ieu157

- Nuhn, T.P. and C.G. Wright. 1979. An Ecological Survey of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a Landscaped Suburban Habitat. American Midland Naturalist 102(2):353-362

- O'Keefe S. T., J. L. Cook, T. Dudek, D. F. Wunneburger, M. D. Guzman, R. N. Coulson, and S. B. Vinson. 2000. The Distribution of Texas Ants. The Southwestern Entomologist 22: 1-92.

- Ouellette G. D. and A. Francoeur. 2012. Formicidae [Hymenoptera] diversity from the Lower Kennebec Valley Region of Maine. Journal of the Acadian Entomological Society 8: 48-51

- Ouellette G. D., F. A. Drummond, B. Choate and E. Groden. 2010. Ant diversity and distribution in Acadia National Park, Maine. Environmental Entomology 39: 1447-1556

- Paiero, S.M. and S.A. Marshall. 2006. Bruce Peninsula Species list . Online resource accessed 12 March 2012

- Parson G. L., G Cassis, A. R. Moldenke, J. D. Lattin, N. H. Anderson, J. C. Miller, P. Hammond, T. Schowalter. 1991. Invertebrates of the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, western Cascade Range, Oregon. V: An annotated list of insects and other arthropods. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-290. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 168 p.

- Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture Collection (Pers. Comm. Sven-Erik Spichiger 23 Dec 2017)

- Piers H. 1922. List of a small collection of ants (Formicidae) obtained in Queen's County, Nova Scotia, by the late Walter H. Prest. Proceedings and Transactions of the Nova Scotian Institute of Science, 15(4), 169-173.

- Prest W. H., and H. Piers. 1922. List of a Small Collection of Ants (Formicidae) obtained in Queen's County, Nova Scotia. Nova Scotian Institute of Science 15(4): 169-173.

- Procter W. 1938. Biological survey of the Mount Desert Region. Part VI. The insect fauna. Philadelphia: Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology, 496 pp.

- Ratchford, J.S., S.E. Wittman, E.S. Jules, A.M. Ellison, N.J. Gotelli and N.J. Sanders. 2005. The effects of fire, local environment and time on ant assemblages in fens and forests. Diversity and Distributions 11:487-497.

- Reddell J. R., and J. C. Cokendolpher. 2001. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from caves of Belize, Mexico, and California and Texas (U.S.A.) Texas. Texas Memorial Museum Speleological Monographs 5: 129-154.

- Rees D. M., and A. W. Grundmann. 1940. A preliminary list of the ants of Utah. Bulletin of the University of Utah, 31(5): 1-12.

- Roeder K. A., and D. V. Roeder. 2016. A checklist and assemblage comparison of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma. Check List 12(4): 1935.

- Rowles, A.D. and J. Silverman. 2009. Carbohydrate supply limits invasion of natural communities by Argentine ants. Oecologia 161(1):161-171

- Ruzsky M. 1946. Ants of Tomsk province and contiguous localities. Tr. Tomsk. Gos. Univ. 97: 69-105

- Ruzsky M. 1946. Ants of Tomsk province and contiguous localities. Trudy Tomskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta 97: 69-72.

- Scholes, D.R. and A. V. Suarez. 2009. Speed-versus-accuracy trade-offs during nest relocation in Argentine ants (Linepithema humile) and odorous house ants (Tapinoma sessile). Insectes Sociaux 56(4):413-418.

- Sharplin, J. 1966. An annotated list of the Formicidae (Hymenoptera) of Central and Southern Alberta. Quaetiones Entomoligcae 2:243-253

- Shik, J., A. Francoeur and C. Buddle. 2005. The effect of human activity on ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) richness at the Mont St. Hilaire Biosphere Reserve, Quebec. Canadian Field-Naturalist 119(1): 38-42.

- Smith M. R. 1928. The biology of Tapinoma sessile Say, an important house-infesting ant. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 21: 307-330.

- Smith M. R. 1934. A list of the ants of South Carolina. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 42: 353-361.

- Smith M. R. 1934. Dates on which the immature or mature sexual phases of ants have been observed (Hymen.: Formicoidea). Entomological News 45: 247-251.

- Smith M. R. 1935. A list of the ants of Oklahoma (Hymen.: Formicidae). Entomological News 46: 235-241.

- Smith M. R. 1962. A new species of exotic Ponera from North Carolina (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Acta Hymenopterologica 1: 377-382.

- Sturtevant A. H. 1931. Ants collected on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Psyche (Cambridge) 38: 73-79

- Talbot M. 1976. A list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Edwin S. George Reserve, Livingston County, Michigan. Great Lakes Entomologist 8: 245-246.

- Toennisson T. A., N. J. Sanders, W. E. Klingeman, and K. M. Vail. 2011. Influences on the Structure of Suburban Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Communities and the Abundance of Tapinoma sessile. Environ. Entomol. 40(6): 1397-1404.

- Turner C. R., and J. L. Cook. 1998. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Caddo Lake region of northeast Texas. Texas Journal of Science 50: 171-173.

- Van Pelt A. 1962. Concerning the sparce ant fauna of Mt. Mitchell. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 78: 138-141.

- Van Pelt A. F. 1948. A Preliminary Key to the Worker Ants of Alachua County, Florida. The Florida Entomologist 30(4): 57-67

- Van Pelt A. F. 1966. Activity and density of old-field ants of the Savannah River Plant, South Carolina. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 82: 35-43.

- Van Pelt A., and J. B. Gentry. 1985. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Savannah River Plant, South Carolina. Dept. Energy, Savannah River Ecology Lab., Aiken, SC., Report SRO-NERP-14, 56 p.

- Viereck H. L. 1903. Hymenoptera of Beulah, New Mexico. [part]. Trans. Am. Entomol. Soc. 29: 56-87.

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Wang C., J. Strazanac and L. Butler. 2000. Abundance, diversity and activity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in oak-dominated mixed Appalachian forests treated with microbial pesticides. Environmental Entomology. 29: 579-586

- Ward P. S. 1987. Distribution of the introduced Argentine ant (Iridomyrmex humilis) in natural habitats of the lower Sacramento Valley and its effects on the indigenous ant fauna. Hilgardia 55: 1-16

- Warren, L.O. and E.P. Rouse. 1969. The Ants of Arkansas. Bulletin of the Agricultural Experiment Station 742:1-67

- Wetterer, J. K.; Ward, P. S.; Wetterer, A. L.; Longino, J. T.; Trager, J. C.; Miller, S. E. 2000. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Santa Cruz Island, California. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 99:25-31.

- Wetterer, J.K., P.S. Ward, A.L. Wetterer, J.T. Longino, J.C. Trager and S.E. Miller. 2000. Ants (Hymenoptera:Formicidae) of Santa Cruz Island, California. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Science 99(1):25-31.

- Wheeler G. C., J. N. Wheeler, and P. B. Kannowski. 1994. Checklist of the ants of Michigan (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). The Great Lakes Entomologist 26(4): 297-310

- Wheeler G. C., and E. W. Wheeler. 1944. Ants of North Dakota. North Dakota Historical Quarterly 11:231-271.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler J. 1989. A checklist of the ants of Oklahoma. Prairie Naturalist 21: 203-210.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1986. The ants of Nevada. Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, vii + 138 pp.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1987. A Checklist of the Ants of South Dakota. Prairie Nat. 19(3): 199-208.

- Wheeler J. N., G. C. Wheeler, R. J. Lavigne, T. A. Christiansen, and D. E. Wheeler. 2014. The ants of Yellowstone National Park. Lexington, Ky. : CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013. 112 pages.

- Wheeler W. M. 1900. The habits of Ponera and Stigmatomma. Biological Bulletin (Woods Hole). 2: 43-69.

- Wheeler W. M. 1904. The ants of North Carolina. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 20: 299-306.

- Wheeler W. M. 1906. Fauna of New England. 7. List of the Formicidae. Occasional Papers of the Boston Society of Natural History 7: 1-24

- Wheeler W. M. 1906. Fauna of New England. 7. List of the Formicidae. Occasional Papers of the Boston Society of Natural History 7: 1-24.

- Wheeler W. M. 1908. The ants of Casco Bay, Maine, with observations on two races of Formica sanguinea Latreille. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 24: 619-645.

- Wheeler W. M. 1916. Formicoidea. Formicidae. Pp. 577-601 in: Viereck, H. L. 1916. Guide to the insects of Connecticut. Part III. The Hymenoptera, or wasp-like insects, of Connecticut. Connecticut State Geological and Natural History Survey. Bulletin 22: 1-824.

- Wheeler W. M. 1917. A list of Indiana ants. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 26: 460-466.

- Wheeler W. M. 1917. The mountain ants of western North America. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 52: 457-569.

- Wheeler W. M. 1928. Ants of Nantucket Island, Mass. Psyche (Cambridge) 35: 10-11.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1978. Mountain ants of Nevada. Great Basin Naturalist 35(4):379-396

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1985. A checklist of Texas ants. Prairie Naturalist 17:49-64.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Montana. Psyche 95:101-114

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Wyoming. Insecta Mundi 2(3&4):230-239

- Wheeler, G.C., J. Wheeler and P.B. Kannowski. 1994. CHECKLIST OF THE ANTS OF MICHIGAN (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE). Great Lakes Entomologist 26:1:297-310

- Wheeler, G.C., J. Wheeler, T.D. Galloway and G.L. Ayre. 1989. A list of the ants of Manitoba. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Manitoba 45:34-49

- Wild A. L. 2009. Evolution of the Neotropical ant genus Linepithema. Systematic Entomology 34: 49-62

- Wing M. W. 1939. An annotated list of the ants of Maine (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News 50:161-165.

- Yap H. H., and C. Y. Lee. 1994. A preliminary study on the species composition of household ants on Penang island, Malaysia. Journal of Bioscience 5(1-2): 64-66.

- Young J., and D. E. Howell. 1964. Ants of Oklahoma. Miscellaneous Publication. Oklahoma Agricultural Experimental Station 71: 1-42.

- Young, J. and D.E. Howell. 1964. Ants of Oklahoma. Miscellaneous Publications of Oklahoma State University MP-71

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Common Name

- Supercolonies

- Facultatively polygynous

- Limited invasive

- Photo Gallery

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- Tropical

- ''Microdon'' fly Associate

- Host of Microdon globosus

- Cricket Associate

- Host of Myrmecophilus pergandei

- Cestode Associate

- Host of Mesocestoides sp.

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Aphis asclepiadis

- Host of Aphis gossypii

- Host of Aphis helianthi

- Host of Aphis lugentis

- Host of Aphis salicariae

- Host of Aphis varians

- Host of Bipersona torticauda

- Host of Brachycaudus cardui

- Host of Chaitophorus populicola

- Host of Chaitophorus populifolii

- Host of Chaitophorus viminalis

- Host of Cinara atlantica

- Host of Cinara pineti

- Host of Cinara ponderosae

- Host of Dysaphis sorbi

- Host of Myzus persicae

- FlightMonth

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Dolichoderinae

- Tapinoma

- Tapinoma sessile

- Dolichoderinae species

- Tapinoma species

- Ssr