Temnothorax rugatulus

| Temnothorax rugatulus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Crematogastrini |

| Genus: | Temnothorax |

| Species group: | rugatulus |

| Species: | T. rugatulus |

| Binomial name | |

| Temnothorax rugatulus (Emery, 1895) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Higher elevation coniferous forest species which occurs in moist habitats, in shaded grassy slopes with pines or grasslands. Temnothorax rugatulus can also be found in pinyon-juniper and cool desert habitats. Nests have been found in the soil, under rocks, in decaying wood, in grasses and in trees. Colonies may be monogynous, typically with a single macrogyne queen, or polygynous, with multiple microgyne queens. (Mackay 2000)

| At a Glance | • Facultatively polygynous • Tandem running |

Identification

Prebus (2017) - A member of the rugatulus clade.

Mackay (2000) - Workers of this species have an 11 segmented antenna, a coarsely rugose dorsal surface of the head, the dorsum (and sides to a lesser extent) of the mesosoma and petiole are rugose as the head, the propodeal spines are well developed, longer than the distance between their bases, the dorsum of the postpetiole has rough punctures.

This species can be recognized by the coarse rugae on the head, the areas between the rugae are punctured, but shiny. This characteristic separates Temnothorax rugatulus from Temnothorax bradleyi and Temnothorax smithi. It is smaller than Temnothorax josephi and is basically concolorous medium yellowish-brown, often with dark infuscation on the head and mesosoma. The node of the petiole is rounded in profile, not truncate as in Temnothorax ambiguus. The subpetiolar process is often about as wide at the tip as it is at the base, although specimens that were previously referred to as Temnothorax rugatulus tend to have a tapered subpetiolar process. The propodeal spines are well developed which separates it from Temnothorax schaumii and Temnothorax whitfordi.

Keys including this Species

- Key to Temnothorax longispinosus species group workers

- Key to Temnothorax of California

- Key to the New World Temnothorax

Distribution

Canada: British Colombia, Alberta. United States: Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas. Mexico: Baja California.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 53.018° to 29.255°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: Canada, United States (type locality).

Neotropical Region: Mexico.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

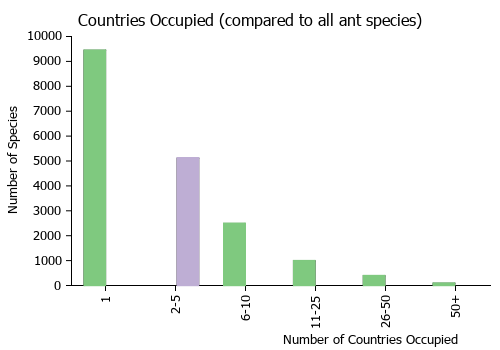

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Habitat

High elevation coniferous forest, shaded grassy slopes with pines or grasslands, pinyon-juniper and cool desert habitats.

Abundance

Common.

Biology

Nests often under rocks and in crevices on the underside of coarse rocks.

Regional Notes

Idaho

Cole (1934): This ant is rather frequent in moist habitats near Twin Falls, Hagerman and Buhl, chiefly along the Snake River. Colonies are small, the workers timid and sluggish and the brood scant. Winged forms appear at Twin Falls in late September.

Nevada

Wheeler and Wheeler (1986): In Nevada Temnothorax rugatulus records are widely scattered, but absent from the southern quarter of the state. We have 30 records from 20 localities; 4,700-9,100 ft., mostly 6,000-7,000 ft. Fifteen records were from the Coniferous Forest Biome, 5 from the Pinyon-Juniper Biome, and 4 from the Cool Desert. Five nests were under stones, 8 were in rotten wood. This is a slow-moving ant.

New Mexico

Cole (1953, 1954): Colonies of Temnothorax rugatulus Emery were observed at an elevation of 6,350 ft. at Bandelier National Monument and 5 mi. E. of Taos, 7,350 ft. At both places nests were common beneath stones on shaded grassy slopes with pines. A number of the colonies was very populous and multiple queens were present.

Foraging/Diet

An study of starvation resistance by Ruppel and Kirkman (2005) produced the following findings.

Most of a set of 21 laboratory colonies were able to survive eight months without any food. Brood decline began first (after two months) and mortality was highest, worker decline was intermediate, and queen mortality started latest and remained lowest. Brood (its relative change during the first four months and the level of brood relative to colony size) was the only significant predictor of colony starvation resistance.

Most colonies survived four months of total starvation without a significant decline. While it was found that the number of brood and workers was dramatically reduced after eight months, this time period exceeds the annual period of productive warm weather activity in most Temnothorax rugatulus habitats.

From this study they conclude that most well-fed colonies could survive a whole season without food. Internal resources and brood are suggested to be the only effective mediators of starvation resistance in this species. The amount of brood continued to increase during the first two months without food, with the brood then becoming a source of nutrients once internal reserves were depleted. Colony size was not shown to provide does not confer any survival advantage.

Colony Attributes

Colony size averaged from 54 to 141 workers (15 subpopulations), with a significant difference between pologyne (91±85 (SD)) and monogyne colonies (65±42). (Rüppell et al. 2001)

Moglich (1978) studying a population of Temnothorax rugatulus in a mixed oak-juniper forest in the Chiricahua Mountains found colonies had an average of 109 workers (range 30 to over 200).

Males fat stores were found to be 10.1±9.0 (SD) μg, n=40; macrogyne fat stores 466.4±146.9 μg, n=35; microgynes fat stores 51.4±12.3 μg, n=10. Relative fat content was not correlated with head width in microgynes (rp=–0.19, P=0.60), but was in macrogynes (rp=0.42, P=0.01).(Rüppell et al. 2001)

Nesting Habits

Nests have been found in the soil, under and between rocks, in decaying wood, in grasses and in trees. Colonies will readily emigrate to new nest locations if a nest or micro-ecological conditions become unfavorable.

Moglich (1978) studying a population of Temnothorax rugatulus in a mixed oak-juniper forest in the Chiricahua Mountains described their nests, which were found under stones. Dry brown oak leaves, juniper needles, little twigs and a diversity of other plant materials formed the bases of the nest chambers, which showed flat, often unbroken surfaces. Thus the whole colony was exposed after the stone was turned. The ants were crowded together either on the top of the material or upside down on the stone ceiling. Sometimes, however, a few small chambers were built into the base of the nest. Although the space covered by the rock measured 219 x 292 cm2 (range 32-1 800 cm2) the nest chambers were considerably smaller (24 x 17 cm2; range 2.4-63 cm2). The walls confining the nest chambers were constructed out of fine material like soil and small vegetation particles. Mean nest density was 1.5 ± 0.9 per 9.3 m2).

Reproduction

There are two queen morphs in Leptothorax rugatulus. Microgynes, slightly larger than worker size, and macrogynes, which are roughly twice as large as workers. Genetic evidence shows that queens in polygynous colonies are related to each other, supporting the hypothesis that colonies with more than one queen commonly arise by the adoption of daughter queens into their natal colonies. The higher fat content of macrogynes, their predominance in monogynous societies and in small founding colonies, and their greater flight activity favor the view that macrogynes predominantly found colonies independently, while microgynes are specialized for dependent colony founding by readoption. Despite the potential for these two mating strategies to lead to the creation of distinctive genetic subpopulations, genetic diversity is likely maintained by queens mating randomly with males. (Rüppell et al. 1998, Rüppell et al. 2001, Rüppell et al. 2003)

Behavior

Nest Migration

Temnothorax rugatulus use both tandem running and carrying behavior during nest emigration. Tandem running is strictly limited to the first phase of nest emigration, whereas carrying behavior is the predominant technique (84 %). Workers which are recruited by tandem running inspect the new nest site. If they accept it, they join the scout force and lead or carry nestmates to the new nest by themselves. (Moglich 1978)

Genetics

Rüppell et al. (2003) examined population genetic consequences of female philopatry. Abstract: Temnothorax rugatulus, an abundant North American ant, displays a conspicuous queen size polymorphism that is related to alternative reproductive tactics. Large queens participate mainly in mating flights and found new colonies independent of their mother colony. In contrast, small queens do not found new colonies independently, but seek readoption into their natal nest which results in multiple-queen colonies (polygyny). Populations differ strongly in the ratio of small to large queens, the prevalent reproductive tactic and colony social structure, according to ecological parameters such as nest site stability and population density. This study compares the genetic structure of two strongly differing populations within the same mountain range. Data from microsatellites and mitochondrial DNA give no evidence for alien reproductives in polygynous colonies. The incidence of alien workers in colonies (as determined by mitochondrial haplotype) was low and did not differ between monogynous and polygynous colonies. We found significant population viscosity (isolation-by-distance) at the mitochondrial level in only the predominantly polygynous population, which supports the theoretical prediction that female philopatry leads to mtDNA-specific population structure. Nuclear and mitochondrial genetic diversity was similar in both populations. The genetic differentiation between the two investigated populations was moderate at the mitochondrial level, but not significantly different from zero when measured with microsatellites, which corroborates limited dispersal of females (but not males) at a larger scale.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Other Insects

- Amecocerus sp. (Coleoptera: Melyridae; det. J.M. Kingsolver) was taken in a nest of Peavine Peak (Washoe Co.) at 6,800 ft. (Wheeler and Wheeler 1986)

- Cysticercoids of a dilepidid cestode were found by dissection of aberrant yellowish workers and virgin queens of the ant Leptothorax rugatulus from several mountain ranges in the southwestern United States. The cestode was not positively identified, but cysticercoids are similar to those of the genus Anomotaenia previously found in related ants. (Heinze et al. 1998)

Cestoda

- This species is a host for the cestode Dilepididae unspecified (cf. Anomotaenia) (a parasite) in Arizona/New Mexico, United States (Heinze et al., 1998; Laciny, 2021).

Life History Traits

- Queen number: monogynous; polygynous (Rüppell and co-authors)

Castes

There are two queen forms, a microgyne and a macrogyne. Queens and males have been collected but have yet to be described.

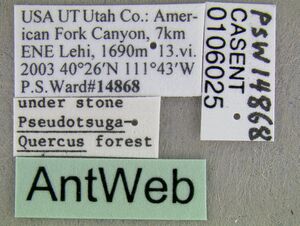

Worker

| |

| . | |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- rugatulus. Leptothorax (Leptothorax) rugatulus Emery, 1895c: 321 (w.) U.S.A. Taber & Cokendolpher, 1988: 95 (k.). Combination in L. (Myrafant): Smith, M.R. 1950: 30; in Temnothorax: Bolton, 2003: 272. Subspecies of curvispinosus: Wheeler, W.M. 1903c: 241. Revived status as species: Wheeler, W.M. 1917a: 509. Senior synonym of annectens, cockerelli, mediorufus: Creighton, 1950a: 269; of brunnescens: Mackay, 2000: 394.

- annectens. Leptothorax curvispinosus subsp. annectens Wheeler, W.M. 1903c: 242, pl. 12, fig. 13 (w.) U.S.A. Subspecies of rugatulus: Wheeler, W.M. 1917a: 510. Junior synonym of rugatulus: Creighton, 1950a: 269.

- brunnescens. Leptothorax rugatulus subsp. brunnescens Wheeler, W.M. 1917a: 510 (w.) U.S.A. Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1955b: 25 (l.). Combination in L. (Myrafant): Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1955b: 25. Senior synonym of dakotensis: Creighton, 1950a: 269. Junior synonym of rugatulus: Mackay, 2000: 394.

- cockerelli. Leptothorax rugatulus var. cockerelli Wheeler, W.M. 1917a: 509 (w.q.) U.S.A. [First available use of Leptothorax curvispinosus subsp. rugatulus var. cockerelli Wheeler, W.M. 1903c: 241; unavailable name.] Junior synonym of rugatulus: Creighton, 1950a: 269.

- mediorufus. Leptothorax rugatulus var. mediorufus Wheeler, W.M. 1917a: 510 (w.q.) U.S.A. Junior synonym of rugatulus: Creighton, 1950a: 269.

- dakotensis. Leptothorax rugatulus subsp. dakotensis Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, E.W. 1944: 247 (w.) U.S.A. Junior synonym of brunnescens: Creighton, 1950a: 269.

Type Material

The original description lists specimens from Colorado and South Dakota. Creighton (1950) gives the type locality as Colorado "by present restriction. Mackay 2000 - American Museum of Natural History, Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, Genoa Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Testacea, capite abdomineque magis minusve (uscatis, capite thoraceque dense punctatis et cum rugis subtilibus longitudinalibus,antennis 11 articulatis, thorace breviusculo, dorso haud impresso, spinis vix curvatis, obliquis, mediocribus, acutis; petioli segmento 1. postice modice incrassato, 2. subtrapezoideo, scapo pedibusque haud pilosis.

Karyotype

- n = 14 (USA) (Fischer, 1987) (as Leptothorax rugatulus).

- 2n = 26 (USA) (Taber & Cokendolpher, 1988) (as Leptothorax rugatulus).

- 2n = 27 (USA) (Taber & Cokendolpher, 1988) (as Leptothorax rugatulus).

Etymology

Morphology, in reference to the rugosity found on the body.

References

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Bhattacharyya, K., Annagiri, S. 2019. Characterization of nest architecture of an Indian ant Diacamma indicum (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of Insect Science 19, 9 (doi:10.1093/jisesa/iez083).

- Bolton, B. 2003. Synopsis and Classification of Formicidae. Mem. Am. Entomol. Inst. 71: 370pp (page 272, Combination in Temnothorax)

- Choppin, M., Graf, S., Feldmeyer, B., Libbrecht, R., Menzel, F., Foitzik, S. 2021. Queen and worker phenotypic traits are associated with colony composition and environment in Temnothorax rugatulus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), an ant with alternative reproductive strategies. Myrmecological News 31: 61-69 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:061).

- Cole, A. C., Jr. 1934. An annotated list of the ants of the Snake River Plains, Idaho (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Psyche (Cambridge). 41:221-227.

- Cole, A. C., Jr. 1953. Notes on the genus Leptothorax in New Mexico and a description of a new species. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 55:27-30.

- Cole, A. C., Jr. 1954. Studies of New Mexico ants. X. The genus Leptothorax (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science. 29:240-241.

- Creighton, W. S. 1950a. The ants of North America. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 104: 1-585 (page 269, Senior synonym of annectens, cockerelli and mediorufus.)

- Doering, G.N., Sheehy, K.A., Barnett, J.B., Pruitt, J.N. 2020. Colony size and initial conditions combine to shape colony reunification dynamics. Behavioural Processes 170, 103994. (doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2019.103994).

- Emery, C. 1895. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. (Schluss). Zoologische Jahrbücher, Abteilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Tiere. 8:257-360. (page 321, worker described)

- Guénard, B., Silverman, J. 2011. Tandem carrying, a new foraging strategy in ants: description, function, and adaptive significance relative to other described foraging strategies. Naturwissenschaften 98(8), 651–659 (doi:10.1007/s00114-011-0814-z).

- Heinze, J., Rueppell, O. 2014. The frequency of multi-queen colonies increases with altitude in a Nearctic ant. Ecological Entomology (2014), 39, 527–529 DOI: 10.1111/een.12119.

- Heinze, J., Rüppell, O., Foitzik, S., Buschinger, A. 1998. First records of Leptothorax rugatulus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with cysticercoids of tapeworms (Cestoda: Dilepididae) from the southwestern United States. Florida Entomologist 81: 122-125 (doi:10.2307/3496004).

- Horna-Lowell, E., Neumann, K.M., O’Fallon, S., Rubio, A., Pinter-Wollman, N. 2021. Personality of ant colonies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) – underlying mechanisms and ecological consequences. Myrmecological News 31: 47-59 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:047).

- Jansen, G., Savolainen, R. 2010. Molecular phylogeny of the ant tribe Myrmicini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 160(3), 482–495 (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00604.x).

- Lorite, P., Palomeque, T. 2010. Karyotype evolution in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with a review of the known ant chromosome numbers. Myrmecological News 13: 89-102.

- Maák, I., Roelandt, G., d'Ettorre, P. 2020. A small number of workers with specific personality traits perform tool use in ants. eLife 9, e61298 (doi:10.7554/elife.61298).

- MacKay, W. P. 2000. A review of the New World ants of the subgenus Myrafant, (genus Leptothorax) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 36: 265-444 (page 394, Senior synonym of brunnescens)

- Mackay, W. P. and E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, NY.

- Mizumoto, N., Tanaka, Y., Valentini, G., Richardson, T. O., Annagiri, S., Pratt, S. C., Shimoji, H. 2023. Functional and mechanistic diversity in ant tandem communication. IScience 26(4), 106418 (doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.106418).

- Möglich, M. 1978. Social organization of nest emigration in Leptothorax (Hym., Form.). Insectes Sociaux. 25:205-225.

- Prebus, M. 2017. Insights into the evolution, biogeography and natural history of the acorn ants, genus Temnothorax Mayr (hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bmc Evolutionary Biology. 17:250. doi:10.1186/s12862-017-1095-8 (The doi link to the publication's journal webpage provides access to the 24 files that accompany this article).

- Prebus, M.M. 2021. Taxonomic revision of the Temnothorax salvini clade (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with a key to the clades of New World Temnothorax. PeerJ 9, e11514 (doi:10.7717/peerj.11514).

- Ramirez-Esquivel, F., Leitner, N.E., Zeil, J., Narendra, A. 2017. The sensory arrays of the ant, Temnothorax rugatulus. Arthropod Structure, Development 46, 552–563 (doi:10.1016/j.asd.2017.03.005).

- Romiguier, J., Borowiec, M. L., Weyna, A., Helleu, Q., Loire, E., La Mendola, C., Rabeling, C., Fisher, B. L., Ward, P. S., Keller, L. 2022. Ant phylogenomics reveals a natural selection hotspot preceding the origin of complex eusociality. Current Biology, 3213, 2942-2947.e4 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.05.001).

- Rüppell, O. and R. W. Kirkman. 2005. Extraordinary starvation resistance in Temnothorax rugatulus (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) colonies: Demography and adaptive behavior. Insectes Sociaux. 52:282-290.

- Rüppell, O., J. Heinze, and B. Hölldobler. 2001. Alternative reproductive tactics in the queen size dimorphic ant Leptothorax rugatulus (Emery) and population genetic consequences. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 50:189-197.

- Rüppell, O., M. Strätz, B. Baier, and J. Heinze. 2003. Mitochondrial markers in the ant Leptothorax rugatulus reveal the population genetic consequences of female philopatry at different hierarchical levels. Molecular Ecology. 12:795-801.

- Rüppell, O.; Heinze, J.; Hölldobler, B. 1998b. Size-dimorphism in the queens of the North American ant Leptothorax rugatulus (Emery). Insectes Soc. 45: 67-77.

- Sasaki, T., Briner, J.E., Pratt, S.C. 2020. The effect of brood quantity on nest site choice in the Temnothorax rugatulus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America (doi:10.1093/AESA/SAAA018).

- Smith, M. R. 1950a. On the status of Leptothorax Mayr and some of its subgenera. Psyche (Camb.) 57: 29-30 (page 30, Combination in L. (Myrafant))

- Snelling, R. R.; Borowiec, M. L.; Prebus, M. M. 2014. Studies on California ants: a review of the genus Temnothorax (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). ZooKeys 372:27-89. doi:10.3897/zookeys.372.6039

- Taber, S. W.; Cokendolpher, J. C. 1988. Karyotypes of a dozen ant species from the southwestern U.S.A. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Caryologia 41: 93-102 (page 95, karyotype described)

- Wheeler, W. M. 1903d. A revision of the North American ants of the genus Leptothorax Mayr. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 55: 215-260 (page 241, Subspecies of curvispinosus)

- Wheeler, W. M. 1917a. The mountain ants of western North America. Proc. Am. Acad. Arts Sci. 52: 457-569 (page 509, Revived status as species)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Allred D. M. 1982. Ants of Utah. The Great Basin Naturalist 42: 415-511.

- Allred, D.M. 1982. The ants of Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 42:415-511.

- Amanda C. S., L. H. Fraser, C. N. Carlyle, and Eleanor R. L. Bassett. 2012. Does Cattle Grazing Affect Ant Abundance and Diversity in Temperate Grasslands? Rangeland Ecology & Management 65(3): 292-298.

- Blacker, N.C. 1992. Some Ants from Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. J. Entomol. Soc. Bri. Columbia 89:3-12.

- Blacker, N.C. 1992. Some ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 89:3-12

- Borchert, H.F. and N.L. Anderson. 1973. The Ants of the Bearpaw Mountains of Montana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 46(2):200-224

- Browne J. T., R. E. Gregg. 1969. A study of the ecological distribution of ants in Gregory Canyon, Boulder, Colorado. University of Colorado Studies. Series in Biology 30: 1-48

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1942. The ants of Utah. American Midland Naturalist 28: 358-388.

- Cole, A.C. 1936. An annotated list of the ants of Idaho (Hymenoptera; Formicidae). Canadian Entomologist 68(2):34-39

- Cover S. P., and R. A. Johnson. 20011. Checklist of Arizona Ants. Downloaded on January 7th at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/AZants-2011%20updatev2.pdf

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Des Lauriers J., and D. Ikeda. 2017. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the San Gabriel Mountains of Southern California, USA with an annotated list. In: Reynolds R. E. (Ed.) Desert Studies Symposium. California State University Desert Studies Consortium, 342 pp. Pages 264-277.

- Downing H., and J. Clark. 2018. Ant biodiversity in the Northern Black Hills, South Dakota (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 91(2): 119-132.

- Emery C. 1895. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. (Schluss). Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Tiere 8: 257-360.

- Foitzik S., and Heinze, J. 1999. Non-random size differences between sympatric species of the ant genus Leptothorax (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomologia Generalis 24: 65-74.

- Gregg, R.T. 1963. The Ants of Colorado.

- Hoey-Chamberlain R. V., L. D. Hansen, J. H. Klotz and C. McNeeley. 2010. A survey of the ants of Washington and Surrounding areas in Idaho and Oregon focusing on disturbed sites (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology. 56: 195-207

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Johnson, R.A. and P.S. Ward. 2002. Biogeography and endemism of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Baja California, Mexico: a first overview. Journal of Biogeography 29:10091026/

- Kannowski P. B. 1956. The ants of Ramsey County, North Dakota. American Midland Naturalist 56(1): 168-185.

- La Rivers I. 1968. A first listing of the ants of Nevada. Biological Society of Nevada, Occasional Papers 17: 1-12.

- Lavigne R., and T. J. Tepedino. 1976. Checklist of the insects in Wyoming. I. Hymenoptera. Agric. Exp. Sta., Univ. Wyoming Res. J. 106: 24-26.

- Mackay W. P. 2000. A review of the New World ants of the subgenus Myrafant, (genus Leptothorax) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 36: 265-444.

- Mackay W. P., and E. E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 400 pp.

- Mackay, W., D. Lowrie, A. Fisher, E. Mackay, F. Barnes and D. Lowrie. 1988. The ants of Los Alamos County, New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). pages 79-131 in J.C. Trager, editor, Advances in Myrmecololgy.

- MontBlanc E. M., J. C. Chambers, and P. F. Brussard. 2007. Variation in ant populations with elevation, tree cover, and fire in a Pinyon-Juniper-dominated watershed. Western North American Naturalist 67(4): 469491.

- Moody J. V., and O. F. Francke. 1982. The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Western Texas Part 1: Subfamily Myrmicinae. Graduate Studies Texas Tech University 27: 80 pp.

- Newton, J.S., J. Glasier, H.E.L. Maw, H.C. Proctor and R.G. Footit. 2011. Ants and subterranean Sternorrhyncha in a native grassland in east-central Alberta, Canada. Canadian Entomologist 143:518-523

- O'Keefe S. T., J. L. Cook, T. Dudek, D. F. Wunneburger, M. D. Guzman, R. N. Coulson, and S. B. Vinson. 2000. The Distribution of Texas Ants. The Southwestern Entomologist 22: 1-92.

- Ostoja S. M., E. W. Schupp, and K. Sivy. 2009. Ant assemblages in intact big sagebrush and converted cheatgrass-dominates habitats in Tooele County, Utah. Western North American Naturalist 69(2): 223234.

- Parson G. L., G Cassis, A. R. Moldenke, J. D. Lattin, N. H. Anderson, J. C. Miller, P. Hammond, T. Schowalter. 1991. Invertebrates of the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, western Cascade Range, Oregon. V: An annotated list of insects and other arthropods. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-290. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 168 p.

- Ratchford, J.S., S.E. Wittman, E.S. Jules, A.M. Ellison, N.J. Gotelli and N.J. Sanders. 2005. The effects of fire, local environment and time on ant assemblages in fens and forests. Diversity and Distributions 11:487-497.

- Smith F. 1941. A list of the ants of Washington State. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist 17(1): 23-28.

- Smith M. R. 1952. On the collection of ants made by Titus Ulke in the Black Hills of South Dakota in the early nineties. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 60: 55-63.

- Snelling R.R., M. L. Borowiec, and M. M. Prebus. 2014. Studies on California ants: a review of the genus Temnothorax (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). ZooKeys 372: 2789. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.372.6039

- Van Pelt, A. 1983. Ants of the Chisos Mountains, Texas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) . Southwestern Naturalist 28:137-142.

- Vasquez-Bolanos M. 2011. Checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Mexico. Dugesiana 18(1): 95-133.

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Ward P. S. 1987. Distribution of the introduced Argentine ant (Iridomyrmex humilis) in natural habitats of the lower Sacramento Valley and its effects on the indigenous ant fauna. Hilgardia 55: 1-16

- Wheeler G. C., and E. W. Wheeler. 1944. Ants of North Dakota. North Dakota Historical Quarterly 11:231-271.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1986. The ants of Nevada. Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, vii + 138 pp.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1987. A Checklist of the Ants of South Dakota. Prairie Nat. 19(3): 199-208.

- Wheeler W. M. 1917. The mountain ants of western North America. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 52: 457-569.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1978. Mountain ants of Nevada. Great Basin Naturalist 35(4):379-396

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1985. A checklist of Texas ants. Prairie Naturalist 17:49-64.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Montana. Psyche 95:101-114

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Wyoming. Insecta Mundi 2(3&4):230-239

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Facultatively polygynous

- Tandem running

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- Nesting Notes

- Cestode Associate

- Host of Dilepididae unspecified (cf. Anomotaenia)

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Myrmicinae

- Crematogastrini

- Temnothorax

- Temnothorax rugatulus

- Myrmicinae species

- Crematogastrini species

- Temnothorax species

- Ssr