Trachymyrmex arizonensis

| Trachymyrmex arizonensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Trachymyrmex |

| Species: | T. arizonensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Trachymyrmex arizonensis (Wheeler, W.M., 1907) | |

This species is common in its preferred habitats within its range. They can often be located by finding a messy soil crater around their nest entrance, along with a distinctive yellowish-gray colored external refuse midden located nearby.

Photo Gallery

Identification

Trachymyrmex arizonensis is often sympatric in central and southern Arizona with the slightly smaller Trachymyrmex carinatus and rarely sympatric with the larger Trachymyrmex nogalensis. It is easily distinguished from all other North American Trachymyrmex by the unusual shape of the frontal lobes in both workers and queens. (Rabeling et al. 2007)

Keys including this Species

Distribution

From Rabeling et al. (2007): Trachymyrmex arizonensis is typically found at mid elevations (1000–2000 m) in mountainous areas within the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Deserts in central and southern Arizona, western New Mexico, and the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora. The species has also been reported from western Texas. Weber identified a single specimen of T. arizonensis from the Chisos Mountains (Van Pelt 1983). It is also reported from west Texas by O’Keefe et al. (2000), but as we have not been able to verify these records, the presence of T. arizonensis in western Texas remains uncertain.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 34.156971° to 24.1°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States (type locality).

Neotropical Region: Mexico.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

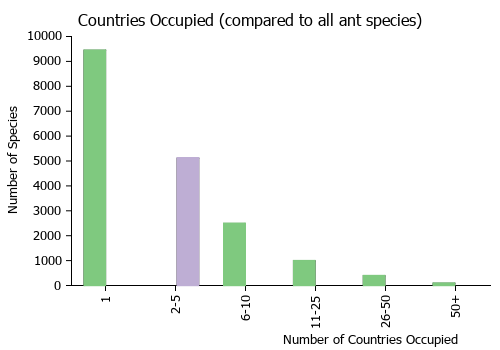

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Habitat

Trachymyrmex arizonensis occurs in a variety of habitats including arid Ocotillo- and Acacia-dominated scrub in mountain foothills, oak-juniperpine woodlands, and relatively mesic mid elevation creek valley forests. (Rabeling et al. 2007)

Biology

|

From Rabeling et al. (2007):

Nests are found under rocks or logs or in open soil, frequently in areas that are partly or lightly shaded. A sloppy crater of excavated soil and a diagnostic yellowish-gray external refuse midden is often present near the nest entrance. Trachymyrmex arizonensis and Trachymyrmex smithi are the only US species of Trachymyrmex that routinely have conspicuous external refuse middens near their nest entrances. Other species occasionally accumulate a small refuse pile close to the nest, but these are usually ephemeral.

Colony-founding queens of T. arizonensis are frequently found under rocks. Older colonies often have 3–5 fungus garden chambers and may contain well over 1000 workers (R.A. Johnson pers. obs.; see also Wheeler 1911).

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Other Ants

From Rabeling et al. (2007): Trachymyrmex arizonensis is associated with Strumigenys arizonica, a tiny dacetine ant that has been found only within or adjacent to T. arizonensis nests (Ward 1988; see also Yéo et al. 2006). Most species in the genus Strumigenys are specialist predators on Collembola and strongly prefer relatively mesic habitats. We suspect that S. arizonica benefits from the controlled, moist microenvironment the Trachymyrmex provide for their fungal symbiont and feeds on the numerous collembolans that live in the chambers and refuse piles of the Trachymyrmex colony (Johnson & Cover, unpublished data).

In the mountains of southern Arizona, two army ant species, Neivamyrmex nigrescens and Neivamyrmex rugulosus, prey on T. arizonensis (Miranda et al. 1980, LaPolla et al. 2002). In Tamaulipas, Mexico, Neivamyrmex texanus was observed raiding a colony of Trachymyrmex saussurei (Rabeling & Sanchez-Peña, unpublished data). Based on these few observations, army ants seem to be important predators of at least some Trachymyrmex species, and their raids may result in a significant brood loss and partial destruction of the fungus garden (LaPolla et al. 2002).

Castes

| |

| . | Owned by Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0000359. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0105872. Photographer Dan Kjar, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by USNM, Washington, DC, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0106047. Photographer Michael Branstetter, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by UCDC, Davis, CA, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- arizonensis. Atta (Trachymyrmex) arizonensis Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 710, pl. 49, figs. 9, 10 (q.m.) U.S.A. (Arizona).

- Type-material: 1 syntype queen, 6 syntype males.

- Type-locality: U.S.A.: Arizona, Cochise County, Palmerlee, 24.viii. (C. Schaeffer).

- Type-depositories: AMNH, MCZC, USNM.

- Wheeler, W.M. 1911e: 93 (w.).

- Combination in Cyphomyrmex (Trachymyrmex): Emery, 1924d: 345;

- combination in Trachymyrmex: Gallardo, 1916b: 242; Creighton, 1950a: 321; Solomon, Rabeling, et al. 2019: 948.

- Status as species: Wheeler, W.M. 1910g: 568; Wheeler, W.M. 1911e: 93 (redescription); Wheeler, W.M. 1911g: 250 (in key); Emery, 1924d: 345; Essig, 1926: 862; Cole, 1937b: 136; Creighton, 1950a: 321; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 830; Hunt & Snelling, 1975: 22; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1411; Bolton, 1995b: 420; Mackay & Mackay, 2002: 246; Rabeling, et al. 2007: 7 (redescription); Sánchez-Peña, et al. 2017: 87 (in key).

- Distribution: Mexico, U.S.A.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

From Rabeling et al. (2007): HL 0.88–1.20, HW 0.88–1.28, CI 96–107, SL 0.92–1.4, SI 103–113, ML 1.28–1.8. Large species (HL 0.88–1.20, HW 0.88–1.28) with relatively long legs and antennae (SI 103–113). Head as long as broad or slightly longer than broad (CI 96–107), gradually tapering anteriorly, widest at midpoint between eye and posterior margin. Frontal lobes well developed and strongly asymmetric, with a long, curving anterior margin that meets the much shorter posterior margin to form an acute angle. A broad notch is formed by the frontal lobe and the posterior continuation of the frontal carinae (Figure 1B). Preocular carinae sharply curving mesially and nearly always distinctly separated from the frontal carinae. Anterolateral promesonotal teeth often sharp, spinelike, directed laterally, not upwards. Propodeal teeth thin, spinelike, strongly divergent in dorsal view, shorter than the distance between their bases. Head, mesosoma and petiole moderately tuberculate, postpetiole and first gastric tergite strongly tuberulate. Color brownish yellow to medium reddish brown.

Queen

From Rabeling et al. (2007): HL 1.19–1.38, HW 1.19–1.38, CI 100, SL 1.25–1.31, SI 96–105, ML 1.88–2.13. As in worker diagnosis, but mesosoma with caste-specific morphology related to wing-bearing and head with minute ocelli. Dorsolateral pronotal teeth large, robust, and tuberculate; ventrolateral pronotal teeth large, blunt, and lacking tuberculi.

Male

From Rabeling et al. (2007): HL 0.98, HW 0.88, CI 93, SL 1.06, SI 121, ML 2.0–2.06. Legs and antennal scapes relatively long. Dorsolateral and ventrolateral pronotal teeth well-developed. Mesoscutum longer than broad, sculpture variable but longitudinal rugulae always present. First gastric tergite with “bumpy” surface. 1–3 toothlike tubercles present on each posterior corner of head and frontal lobes bluntly triangular, more or less symmetrical.

Etymology

Since Wheeler (1907, 1911) collected both the type series and subsequently the workers of Trachymyrmex arizonensis in southeast Arizona, the collection locality clearly motivated the species name. (Rabeling et al. 2007)

References

- Aguilar-Méndez, M.J., Rosas-Mejía, M., Vásquez-Bolaños, M., González-Hernández, G.A., Janda, M. 2021. New distributional records for ants and the evaluation of ant species richness and endemism patterns in Mexico. Biodiversity Data Journal 9, e60630 (doi:10.3897/bdj.9.e60630).

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Booher, D.B. 2021. The ant genus Strumigenys Smith, 1860 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in western North America north of Mexico. Zootaxa 5061, 201–248 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5061.2.1).

- Gallardo, A. 1916c. Notas acerca de la hormiga Trachymyrmex pruinosus Emery. An. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. B. Aires 28: 241-252 (page 242, Combination in Trachymyrmex)

- Gray, K.W., Cover, S.P., Johnson, R.A., Rabeling, C. 2018. The dacetine ant Strumigenys arizonica, an apparent obligate commensal of the fungus-growing ant Trachymyrmex arizonensis in southwestern North America. Insectes Sociaux 65, 401–410 (doi:10.1007/S00040-018-0625-8).

- Jansen, G., Savolainen, R. 2010. Molecular phylogeny of the ant tribe Myrmicini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 160(3), 482–495 (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00604.x).

- La Polla, J. S., Mueller, U. G., Seid, M. & Cover, S. P. (2002) Predation by the army ant Neivamyrmex rugulosus' on the fungus-growing ant Trachymyrmex arizonensis. Insectes Sociaux, 49, 251–256.

- Matthews, A.E., Rowan, C., Stone, C., Kellner, K., Seal, J.N. 2020. Development, characterization, and cross-amplification of polymorphic microsatellite markers for North American Trachymyrmex and Mycetomoellerius ants. BMC Research Notes 13, 173 (doi:10.1186/s13104-020-05015-3).

- Mirenda, J. T., Eakins, D.G., Gravelle, K. & Topoff, H. (1980) Predatory behavior and prey selection by army ants in a desert-grassland habitat. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 7, 119–127.

- Mueller, U.G., Ishak, H.D., Bruschi, S.M., Smith, C.C., Herman, J.J., Solomon, S.E., Mikheyev, A.S., Rabeling, C., Scott, J.J., Cooper, M., Rodrigues, A., Ortiz, A., Brandão, C.R.F., Lattke, J.E., Pagnocca, F.C., Rehner, S.A., Schultz, T.R., Vasconcelos, H.L., Adams, R.M.M., Bollazzi, M., Clark, R.M., Himler, A.G., LaPolla, J.S., Leal, I.R., Johnson, R.A., Roces, F., Sosa-Calvo, J., Wirth, R., Bacci, M. 2017. Biogeography of mutualistic fungi cultivated by leafcutter ants. Molecular Ecology 26, 6921–6937 (doi:10.1111/mec.14431).

- O’Keefe, S. T., Cook J. L., Dudek T., Wunneburger D. F., Guzman M. D., Coulson R. N. & Vinson S. B. (2000). The distribution of Texas ants. Southwestern Entomologist, 22 (Supplement), 1–93.

- Rabeling C., Cover S.P., Mueller U.G. and Johnson R.A. 2007. A review of the North American species of the fungus-gardening ant genus Trachymyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa. 1664:1-54.

- Solomon, S.E., Rabeling, C., Sosa-Calvo, J., Lopes, C.T., Rodrigues, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci Jr, M., Mueller, U.G., Schultz, T.R. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939-956 (doi:10.1111/syen.12370).

- Van Pelt, A. F. 1983. Ants of the Chisos Mountains, Texas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Southwestern Naturalist. 28:137-142.

- Ward, P. S. 1988. Mesic elements in the western Nearctic ant fauna: taxonomic and biological notes on Amblyopone, Proceratium, and Smithistruma (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 61:102-124.

- Wheeler, W. M. 1907d. The fungus-growing ants of North America. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 23: 669-807 (page 710, p.. 49, figs. 9, 10 queen, male described)

- Wheeler, W. M. 1911e. Two fungus-growing ants from Arizona. Psyche (Camb.) 18: 93-101 (page 93, worker described)

- Yéo, K., Molet, M. & Peeters, C. (2006) When David and Goliath share a home: compound nesting of Pyramica and Platythyrea ants. Insectes Sociaux, 53, 435–438.

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Andersen A. N. 1997. Functional Groups and Patterns of Organization in North American Ant Communities: A Comparison with Australia. Journal of Biogeography. 24: 433-460

- Cover S. P., and R. A. Johnson. 20011. Checklist of Arizona Ants. Downloaded on January 7th at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/AZants-2011%20updatev2.pdf

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Eastlake Chew A. and Chew R. M. 1980. Body size as a determinant of small-scale distributions of ants in evergreen woodland southeastern Arizona. Insectes Sociaux 27: 189-202

- Gray K. W., S. P. Cover, R. A. Johnson, and C. Rabeling. 2018. The dacetine ant Strumigenys arizonica, an apparent obligate commensal of the fungus-growing ant Trachymyrmex arizonensis in southwestern North America. Insectes Sociaux 65: 401–410.

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Kay, A. 2002. Applying Optimal Foraging Theory to Assess Nutrient Availability Ratios for Ants. Ecology 83(7):1935-1944

- Klingenberg, C. and C.R.F. Brandao. 2005. The type specimens of fungus growing ants, Attini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Myrmicinae) deposited in the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil. Papeis Avulsos de Zoologia 45(4):41-50

- LaPolla, J.S., U.G. Mueller, M. Seid and S.P. Cover. 2002. Predation by the army ant Neivamyrmex rugulosus on the fungus-growing ant Trachymyrmex arizonensis. Insectes Sociaux 251-256

- Mackay W. P., and E. E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 400 pp.

- O'Keefe S. T., J. L. Cook, T. Dudek, D. F. Wunneburger, M. D. Guzman, R. N. Coulson, and S. B. Vinson. 2000. The Distribution of Texas Ants. The Southwestern Entomologist 22: 1-92.

- Pape R. B., and B. M. O'connor. 2014. Diversity and ecology of the macro-invertebrate fauna (Nemata and Arthropoda) of Kartchner Caverns, Cochise County, Arizona, United States of America. Checklist 10(4): 761-794.

- Rabeling C., S. P. Cover, R. A. Johnson, and U. G. Mueller. 2007. A review of the North American species of the fungus-gardening ant genus Trachymyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 1664: 1-53

- Solomon S. E., C. Rabeling, J. Sosa-Calvo, C. Lopes, A. Rodrigues, H. L. Vasconcelos, M. Bacci, U. G. Mueller, and T. R. Schultz. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939–956.

- Van Pelt, A. 1983. Ants of the Chisos Mountains, Texas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) . Southwestern Naturalist 28:137-142.

- Vasquez-Bolanos M. 2011. Checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Mexico. Dugesiana 18(1): 95-133.

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Wheeler W. M. 1907. The fungus-growing ants of North America. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 23: 669-807.

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Photo Gallery

- North subtropical

- Ant Associate

- Host of Strumigenys arizonica

- Host of Neivamyrmex nigrescens

- Host of Neivamyrmex rugulosus

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Myrmicinae

- Attini

- Trachymyrmex

- Trachymyrmex arizonensis

- Myrmicinae species

- Attini species

- Trachymyrmex species