Anochetus incultus

| Anochetus incultus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Ponerinae |

| Tribe: | Ponerini |

| Genus: | Anochetus |

| Species: | A. incultus |

| Binomial name | |

| Anochetus incultus Brown, 1978 | |

The type material was collected from leaf litter samples.

Identification

Brown (1978) - Similar to Anochetus risii, but smaller and darker: deep reddish-brown, with mandibles, antennae, legs, cheeks and gastric apex lighter, more yellowish.

Zettel (2012) - Anochetus incultus is a species of the A. risii group (Brown 1978). It was described from five workers and a gyne from Mt. Makiling in Laguna Province; no further record was published. One examined worker from the type locality is much smaller than the types (TL 4.4 mm vs. 4.8-5.2 mm) and has a reduced sculpture on frons and pronotum, but is probably conspecific. The gyne from Quezon Province agrees well with the description of the paratype gyne (Brown 1978) except for smaller size (TL 5.0 mm vs. 5.6 mm).

Keys including this Species

- Key to Anochetus of the Philippines

- Key to the Anochetus Species of Asia, Melanesia and the Pacific Region

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 14.155193° to 1.383329988°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Indo-Australian Region: Borneo, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines (type locality), Singapore.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

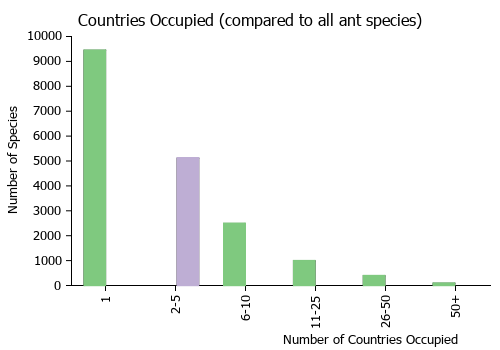

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Castes

Males are unknown for this species.

Worker

| |

| . | Owned by Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- incultus. Anochetus incultus Brown, 1978c: 578, fig. 37 (w.q.) PHILIPPINES (Luzon).

- Type-material: holotype worker, 4 paratype workers, 1 paratype queen.

- Type-locality: holotype Philippines: Luzon, Laguna Prov., Mt Makiling, nr Los Baños, 2.iii.1968 (R.A. Morse); paratypes: 3 workers, 1 queen with same data, 1 worker with same data but undated (F.X. Williams).

- Type-depositories: MCZC (holotype); BMNH, MCZC (paratypes).

- Status as species: Bolton, 1995b: 64; Pfeiffer, et al. 2011: 55; Zettel, 2012: 164; Wang, W.Y., Soh, et al. 2022: 115.

- Distribution: Borneo, Philippines (Luzon), Singapore.

Description

Worker

holotype: TL 5.2, HL 1.20, HW 1.07, ML 0.81, WL 1.66, scape L 1.08, eye L 0.17 mm; CI 89, MI 68.

Similar to Anochetus risii, but smaller and darker: deep reddish-brown, with mandibles, antennae, legs, cheeks and gastric apex lighter, more yellowish. Also the following differences:

1. Eyes smaller; EL/HL 0.14-0.16, vs. 0.17-0.20 in risii. Ocular prominences strongly projecting laterad.

2. Mandibles long, but not quite as long relatively as in risii, which has MI 72-77 in the few samples examined. Denticles on mesal ventral margins of mandibles small and blunt, ordinarily hidden beneath edentate dorsal margin when head is viewed full-face.

3. Pronotal disc behind anterior transverse costulation is shining but thickly covered discad with fairly coarse, vermiculate, predominantly longitudinal rugulae or costulae. Sides of pronotum obliquely to vertically rugulo-striate more finely, except for a variable lower posterior section that tends to be smooth and shining (Pronotal sculpture not shown in fig. 37). Mesonotum vaguely transversely rugulose, but longitudinally costulate behind, continuing into metanotal saddle (fig. 37), Mesopleura smooth and shining, except for striate posterior end.

4. Petiolar node in side view tapering evenly to a narrowly rounded summit (fig. 37); convex-sided in front view, then tapering to a rounded summit. Petiole with a longer anterior pedunculate section than in risii. Node (and gaster) smooth and shining.

5. Funicular antennomeres shorter than in risii; II through IV only about twice as long as broad, or slightly less (in risii L 2-3 times breadth for the same antennomeres).

6. Erect pilosity somewhat less abundant and shorter than in risii. Pubescence nearly obsolete except on appendages.

Worker paratypes (4): TL 4.9-5.2, HL 1.13-1.22, HW 1.01-1.09, ML 0.78-0.82, WL 1.53-1.70, scape L 1.01-1.09, eye L 0.16-0.20 mm; CI 89, MI 67-69.

Intercalary tooth of mandibular apex (on ventral apical tooth) may be missing or nearly so, apparently due to wear or breakage; fine and acute in one young specimen. Pronotal sculpture variable in orientation on pronotum; in one worker the rugulae form a transverse band across the posterior end of the disc.

Queen

dealate: TL 5.6, HL 1.24, HW 1.16, ML 0.82, WL 1.76, scape L 1.09, eye L 0.27 mm; CI 93, MI 66. Pronotum shining, transversely rugose or costate. Mesonotum smooth and shining. Frontal striation weak, fine, confined to space just inside frontal carinae; this striation more delicate in both worker and queen than in risii of corresponding castes. Petiolar node slightly thinner in side view than in workers; i.e., it is axially compressed, with anterior and posterior surfaces converging very gradually. Gaster larger than in worker.

Type Material

Holotype Museum of Comparative Zoology and 4 paratype workers (MCZC, The Natural History Museum), plus one dealate queen, all labeled as from Mt. Makiling, near Los Baños, Laguna Prov., Luzon, Philippines. A single paratype was collected (date not recorded) by F. X. Williams; the remainder of the specimens, including the holotype, came from two samples of leaf litter collected near the summit of the mountain in February and March 1968, run through the Berlese funnel by R. A. Morse.

References

- Brown, W. L., Jr. 1978c. Contributions toward a reclassification of the Formicidae. Part VI. Ponerinae, tribe Ponerini, subtribe Odontomachiti. Section B. Genus Anochetus and bibliography. Stud. Entomol. 20: 549-638 (page 578, fig. 37 worker, queen described)

- General, D. and G. Alpert. 2012. A synoptic review of the ant genera (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of the Philippines. ZooKeys. 200:1-111 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.200.2447.

- General, D.E.M., Buenavente, P.A.C., Rodriguez, L.J.V. 2020. A preliminary survey of nocturnal ants, with novel modifications for collecting nocturnal arboreal ants. Halteres 11: 1-12 (doi:10.5281/ZENODO.3707151).

- Ngô-Muller V., Garrouste R., Schubnel T., Pouillon J.-M., Christophersen V., Christophersen N., Nel A. 2021. The first representative of the trap-jaw ant genus Anochetus Mayr, 1861 in Neogene amber from Sumatra (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Comptes Rendus Palevol 20(2): 21-27 (doi:10.5852/cr-palevol2021v20a2).

- Wang, W.Y., Soh, E.J.Y., Yong, G.W.J., Wong, M.K.L., Benoit Guénard, Economo, E.P., Yamane, S. 2022. Remarkable diversity in a little red dot: a comprehensive checklist of known ant species in Singapore (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with notes on ecology and taxonomy. Asian Myrmecology 15: e015006 (doi:10.20362/am.015006).

- Zettel, H. 2012. New trap-jaw ant species of Anochetus MAYR, 1861 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the Philippine Islands, a key and notes on other species. Myrmecological News 16: 157-167.

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Brown Jr., W.L. 1978. Contributions toward a reclassification of the Formicidae. Part VI. Ponerinae, Tribe Ponerini, Subtribe Odontomachiti, Section B. Genus Anochetus and Bibliography. Studia Entomologia 20(1-4): 549-XXX

- Brown W.L. Jr. 1978. Contributions toward a reclassification of the Formicidae. Part VI. Ponerinae, tribe Ponerini, subtribe Odontomachiti. Section B. Genus Anochetus and bibliography. Studia Ent. 20(1-4): 549-638.

- CSIRO Collection

- Pfeiffer M.; Mezger, D.; Hosoishi, S.; Bakhtiar, E. Y.; Kohout, R. J. 2011. The Formicidae of Borneo (Insecta: Hymenoptera): a preliminary species list. Asian Myrmecology 4:9-58

- Woodcock P., D. P. Edwards, R. J. Newton, C. Vun Khen, S. H. Bottrell, and K. C. Hamer. 2013. Impacts of Intensive Logging on the Trophic Organisation of Ant Communities in a Biodiversity Hotspot. PLoS ONE 8(4): e60756. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060756

- Woodcock P., D. P. Edwards, T. M. Fayle, R. J. Newton, C. Vun Khen, S. H. Bottrell, and K. C. Hamer. 2011. The conservation value of South East Asia's highly degraded forests: evidence from leaf-litter ants. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 366: 3256-3264.

- Zettel H. 2012. New trap-jaw ant species of Anochetus Mayr, 1861 (Hymenopter: Formicidae) from the Philippine Islands, a key and notes on other species. Myrmecological News 16: 157-167.