Dorymyrmex smithi

| Dorymyrmex smithi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Dolichoderinae |

| Tribe: | Leptomyrmecini |

| Genus: | Dorymyrmex |

| Species: | D. smithi |

| Binomial name | |

| Dorymyrmex smithi Cole, 1936 | |

This species is a temporary social parasite, establishing new colonies with the assistance of a host species. It is known to use Dorymyrmex insanus as a host.

| At a Glance | • Temporary parasite |

Photo Gallery

Identification

Keys including this Species

- Key to Dorymyrmex of SE United States queens

- Key to Dorymyrmex of SE United States workers

- Key to Nearctic Dorymyrmex

Distribution

Snelling (1995) - North Dakota to eastern Colorado and New Mexico, east through Texas to North Carolina and Florida.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 43.23791667° to 14.99541667°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States (type locality).

Neotropical Region: Mexico.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

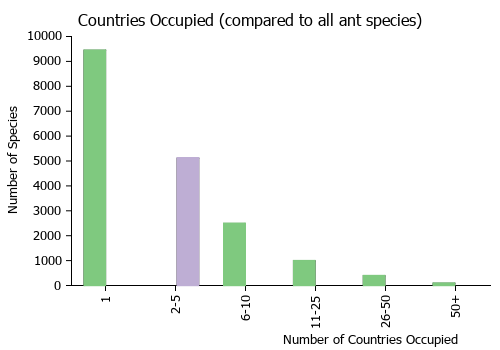

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Biology

Trager (1988), for D. medeis - Due largely to the work of Whitcomb and Nickerson (Whitcomb et al. 1972, Nickerson 1976, Nickerson et al. 1975a, 1975v, 1976, Buren et al. 1975, Nickerson & Whitcomb, in press.) Dorymyrmex medeis (which had gone by the name Dorymyrmex insanus since Snellings 1973 paper) is biologically the best known Dorymyrmex. The following is summarized from these authors' work, plus more recent observations of my own.

Populations of D. medeis are found in those habitats preferred by their host species, D. bureni, i.e., dunes, old fields, roadsides, lawns, pastures, and unpaved roadbeds. A mature colony typically occupies multiple nests. Nickerson et al. (1975a) counted up to 400 nest entrances, up to a meter or more apart, occupied by one unusually large colony. In that study, the queens and eggs were found in only one or a few adjacent nests, and the remaining nests contained only workers and more mature brood. However. Buren et al. (1975) presented evidence that queens may be more dispersed within nest-clusters.

Colonies are thought to be founded by temporary social parasitism, in which newly mated queens of D. medeis enter (weak?) colonies of D. bureni and become accepted by the workers of that colony, who then rear out her offspring. A colony with a mixed worker population ensues. This was first reported by Buren et al. (1975), and I have since observed such mixed colonies on several occasions. I once reared a small mixed colony by introducing a D. medeis queen into a group of about 50 D. bureni workers and brood. The workers accepted the new queen without aggression and reared out about 20 D. medeis workers in a few weeks. Shortly thereafter, the queen was found dead. Apparently, this mixed population stage in the development of a young D. medeis colony is a treacherous one in the life cycle, for the three such colonies I have observed in the field disappeared within a few weeks of their discovery, apparently never reaching maturity.

It turns out that nests with mixed D. medeis-D. bureni populations have two distinct origins. One is that described above: new colony foundation. The second method by which mixed nest may arise is by invasion of D. medeis workers from mature colonies into D. bureni nests near the periphery of their nest clusters. I have twice seen known D. bureni nests near D. medeis colonies become mixed nests during a period of a few days when they went unobserved. Trails of D. medeis workers connected these mixed nests to pure D. medeis nests nearby. A few weeks later, all the D. bureni workers had disappeared. Mapping of ant populations in a pasture over a period of nearly 3 years in north central Florida (Stimac, Trager & Wood, unpublished observations) indicates that D. medeis colonies extend their territories pseudopodium-like into surrounding D. bureni populations, at least in part by invasion of the nests of the latter and temporary mixed colony formation. This seems to be a new variation on the recurrent theme of slave-taking in ants. Since mixed colonies are temporary in nature, the Dorymyrmex situation does not fit neatly under the term dulosis, but bears significantly on the hypothesis of Darwin (1859), and modifications thereof by Buschinger (1986), on the origins of dulosis. This is the first report of what might be called incipient dulosis in the Dolichoderinae.

D. medeis is a highly aggressive ant which allows few other ants to nest within its territories. Nickerson et al. (1975b) showed that only 3% of newly mated Solenopsis invicta queens alighting within D. medeis populations were able to escape predation. Nickerson & Whitcomb (in press) also report that D. medeis visits and protects at least 27 species of honeydew secreting Homoptera in 7 families, and may locate new nests near plants infested with these insects. The presence of Homoptera appears to increase protection of soybeans by D. medeis from folivores. Nickerson's work was initiated to determine suitability of D. medeis for biological control of soybean pests.

Mating flights of this species occur on warm, humid overcast afternoons virtually year-round. Collections of sexuals taken outside the nest span the months of February to October.

D. medeis and the next species (Dorymyrmex reginicula) are closely related and nearly similar species heretofore lumped with the enigmatic D. insanus and its supposed synonym Dorymyrmex smithi.

D. insanus and D. smithi are western species, while D. medeis and D. reginicula are apparently strictly southeastern. The revision of these four species and their relatives is beyond the scope of this paper, but suffice it to say here that while the workers of these four species are often difficult to distinguish (especially D. reginicula and D. smithi) the queens are separated by consistently distinctive morphological and metric characteristics, and I do not hesitate to state that they are all good species.

Castes

Worker

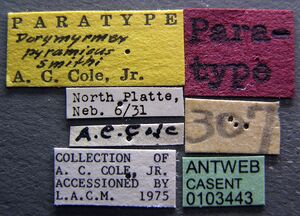

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Paratype of Dorymyrmex smithi. Worker. Specimen code casent0103443. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by LACM, Los Angeles, CA, USA. |

| |

| Paratype of Dorymyrmex smithi. Worker. Specimen code casent0103445. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by LACM, Los Angeles, CA, USA. |

| |

| Holotype of Dorymyrmex smithi. Worker. Specimen code casent0103446. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by LACM, Los Angeles, CA, USA. |

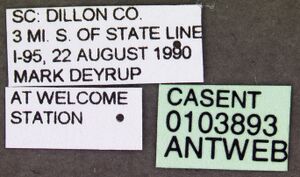

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0103893. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

Queen

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Paratype of Dorymyrmex smithi. Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0103444. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by LACM, Los Angeles, CA, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- smithi. Dorymyrmex pyramicus var. smithi Cole, 1936b: 120 (w.) U.S.A. Combination in Conomyrma: Snelling, R.R. 1973b: 4; in Dorymyrmex: Snelling, R.R. 1995: 7. Junior synonym of pyramicus: Creighton, 1950a: 349; of insanus: Snelling, R.R. 1973b: 5. Revived from synonymy, raised to species and senior synonym of medeis: Snelling, R.R. 1995: 7.

Description

References

- Cantone S. 2018. Winged Ants, The queen. Dichotomous key to genera of winged female ants in the World. The Wings of Ants: morphological and systematic relationships (self-published).

- Cole, A. C., Jr. 1936b. Descriptions of seven new western ants. (Hymenop.: Formicidae). Entomol. News 47: 118-121.(page 120, worker described)

- Creighton, W. S. 1950a. The ants of North America. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 104: 1-585 (page 349, Combination in D. (Conomyrma), Junior synonym of pyramicus)

- Godfrey, R.K., Oberski, J.T., Allmark, T., Givens, C., Hernandez-Rivera, J., Gronenberg, W. 2021. Olfactory system morphology suggests colony size drives trait evolution in Odorous Ants (Formicidae: Dolichoderinae). Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9, 733023 (doi:10.3389/fevo.2021.733023).

- MacGown, J.A., Booher, D., Richter, H., Wetterer, J.K., Hill, J.G. 2021. An updated list of ants of Alabama (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with new state records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 147: 961-981 (doi:10.3157/061.147.0409).

- Oberski, J.T. 2022. First phylogenomic assessment of the amphitropical New World ant genus Dorymyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), a longstanding taxonomic puzzle. Insect Systematics and Diversity 6(1): 8; 1–10 (doi:10.1093/isd/ixab022).

- Snelling, R. R. 1973b. The ant genus Conomyrma in the United States (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Contr. Sci. (Los Angel.) 238: 1-6 (page 4, Combination in Conomyrma; page 5, Junior synonym of insanus)

- Snelling, R. R. 1995a. Systematics of Nearctic ants of the genus Dorymyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Contr. Sci. (Los Angel.) 454: 1-14 (page 7, Combination in Dorymyrmex, Revived from synonymy, raised to species, and senior synonym of medeis)

- Trager, J.C. 1988. A revision of Conomyrma (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the southeastern United States, especially Florida, with keys to the species. Florida Entomologist 71: 11-29.

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Annotated Ant Species List Ordway-Swisher Biological Station. Downloaded at http://ordway-swisher.ufl.edu/species/os-hymenoptera.htm on 5th Oct 2010.

- Bestelmeyer B. T., and J. A. Wiens. 2001. Local and regional-scale responses of ant diversity to a semiarid biome transition. Ecography 24: 381-392.

- Dash S. T. and L. M. Hooper-Bui. 2008. Species diversity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Louisiana. Conservation Biology and Biodiversity. 101: 1056-1066

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Deyrup, M. and J. Trager. 1986. Ants of the Archbold Biological Station, Highlands County, Florida (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Florida Entomologist 69(1):206-228

- Forster J.A. 2005. The Ants (hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Alabama. Master of Science, Auburn University. 242 pages.

- Graham J.H., H.H. Hughie, S. Jones, K. Wrinn, A.J. Krzysik, J.J. Duda, D.C. Freeman, J.M. Emlen, J.C. Zak, D.A. Kovacic, C. Chamberlin-Graham, H. Balbach. 2004. Habitat disturbance and the diversity and abundance of ants (Formicidae) in the Southeastern Fall-Line Sandhills. 15pp. Journal of Insect Science. 4: 30

- Graham, J.H., A.J. Krzysik, D.A. Kovacic, J.J. Duda, D.C. Freeman, J.M. Emlen, J.C. Zak, W.R. Long, M.P. Wallace, C. Chamberlin-Graham, J.P. Nutter and H.E. Balbach. 2008. Ant Community Composition across a Gradient of Disturbed Military Landscapes at Fort Benning, Georgia. Southeastern Naturalist 7(3):429-448

- Guénard B., K. A. Mccaffrey, A. Lucky, and R. R. Dunn. 2012. Ants of North Carolina: an updated list (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 3552: 1-36.

- Hill J.G. & Brown R. L. 2010. The Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Fauna of Black Belt Prairie Remnants in Alabama and Mississippi. Southeastern Naturalist. 9: 73-84

- Ivanov K., L. Hightower, S. T. Dash, and J. B. Keiper. 2019. 150 years in the making: first comprehensive list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Virginia, USA. Zootaxa 4554 (2): 532–560.

- Kay, A. 2002. Applying Optimal Foraging Theory to Assess Nutrient Availability Ratios for Ants. Ecology 83(7):1935-1944

- LeBrun, E.G. 2005. Who Is the Top Dog in Ant Communities? Resources, Parasitoids, and Multiple Competitive Hierarchies. Oecologia 142(4):643-652

- MacGown J. A., J. G. Hill, and M. Deyrup. 2009. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Little Ohoopee River Dunes, Emanuel County, Georgia. J. Entomol. Sci. 44(3): 193-197.

- MacGown, J.A and J.A. Forster. 2005. A preliminary list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Alabama, U.S.A. Entomological News 116(2):61-74

- Mackay W. P., and E. E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 400 pp.

- O'Keefe S. T., J. L. Cook, T. Dudek, D. F. Wunneburger, M. D. Guzman, R. N. Coulson, and S. B. Vinson. 2000. The Distribution of Texas Ants. The Southwestern Entomologist 22: 1-92.

- Trager J. C. 1988. A revision of Conomyrma (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the southeastern United States, especially Florida, with keys to the species. Florida Entomologist 71: 11-29

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Ant Associate

- Host of Dorymyrmex insanus

- Temporary parasite

- Photo Gallery

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- Tropical

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Dolichoderinae

- Leptomyrmecini

- Dorymyrmex

- Dorymyrmex smithi

- Dolichoderinae species

- Leptomyrmecini species

- Dorymyrmex species

- Need Overview

- Need Body Text