Prenolepis imparis

| Prenolepis imparis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Formicinae |

| Tribe: | Lasiini |

| Genus: | Prenolepis |

| Species: | P. imparis |

| Binomial name | |

| Prenolepis imparis (Say, 1836) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Prenolepis imparis, the winter ant, builds deep underground nests. Colonies will seal themselves in their nests during the warmest months of the year and maintain themselves for months in the deepest, coolest chambers. In many parts of its range Prenolepis imparis actively forages during times of the year when the temperature is much cooler than other ant species will tolerate. This helps avoid competition with most co-occuring ant species. Repletes are present in the colony and store fat reserves in their distended gasters.

| At a Glance | • Polygynous • Replete Workers |

Photo Gallery

Identification

Williams and LaPolla (2016) - Obtusely angled propodeum with flat dorsal and posterior faces; entire cuticle smooth and shiny; ectal surface of mandibles with deep longitudinal striations.

This species bears a strong morphological resemblance to Prenolepis nitens but has a different distribution and a more slender mesosoma at the mesonotal constriction. Several key differences can also be seen in male genitalia between P. imparis and P. nitens (see notes under P. nitens).

This species has a wide distribution and shows high morphological variation in the worker caste. As a consequence, many synonyms have been created with descriptions based on variation in color, size, and minor differences in propodeum shape.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 47.3667° to 18.5666°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States (type locality).

Neotropical Region: Mexico (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

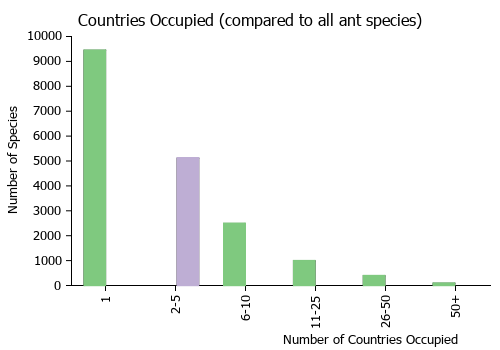

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Biology

Williams and LaPolla (2016) - In P. imparis, colonies are polygynous, but contain relatively small numbers of workers (typically a few thousand workers in a colony) (Wheeler & Wheeler 1986; Tschinkel 1987). The nests of P. imparis are exceedingly deep with no chambers found shallower than 60 centimeters below the ground surface and going down as far as 3.6 m (Tschinkel 1987). False honey ants are peculiar in that the workers are cold-tolerant and forage during the cooler months when most other ant species are inactive. The colony enters an estivation period and becomes inactive above ground for the warmer months, during which time eggs are laid and brood are reared. Reproductives overwinter and emerge on the first warm day of spring for their nuptial flight. One characteristic of P. imparis colonies is the presence of workers with greatly extended gasters. Corpulents were once believed to be true repletes like those of genus Myrmecocystus (Wheeler 1930a; Talbot 1943) until Tschinkel (1987) determined that their enlarged state is actually caused by hypertrophied fat bodies and not the result of crop distention from retained liquid food. Prenolepis imparis is a generalist omnivore (Wheeler 1930a).

Wheeler (1930) - The ant is very timid and retiring and perhaps to some extent crepuscular or even nocturnal. At least it seems to avoid the open sunlight and to be most active in the shade and on cool or cloudy days. I have found the young dealated queens, which closely resemble those of Lasius niger, founding independent incipient colonies in small chambers in the soil.

The food of P. imparis consists of liquids, especially the “honey-dew” of aphids and coccids, the nectar of flowers and extrafloral nectaries, the exudates of living oak-galls, the juices of dead earthworms and those derived from the young tissues of plants. These various liquids are imbibed in such quantities by the foraging workers that their gasters become greatly distended. (Fig. 3) and make their gait very unsteady. In this condition they are really “repletes” like those of the true honey-ants of the Southwestern States and Mexico (Myrmecocystus melliger and mexicanus). The feeding of imparis (var. californica) on young plant-tissues has been recently called to my attention by Mr. H. M. Armitage and indicates that these small timid ants may become of some economic importance. He writes me that in Los Angeles County, Cal., they “were observed feeding extensively not only on the calyx and unopened petals of fruit buds of oranges, but also on the tender new growth. This condition was credited to the fact that the ants become active before the normal citrus bloom and at a time when little natural feeding was available.” Mr. A. C. Burrill has recently made very interesting observations on the feeding habits of imparis and its singular resistance to cold in the Arnold Arboretum at Forest Hills, Mass., and in Missouri, and permits me to quote some of his unpublished notes:

“'I was led to make continuous observations on P. imparis after casually noticing that it appeared at the surface of the soil later in the fall and earlier in the spring than any of our other ants. During the rather warm winter of 1927-28 I selected for daily observation a nest with two entrances in the Arnold Arboretum. The workers were observed to come out onto the surface of the soil nearly every week throughout the winter. The lowest temperatures recorded when the ant came out were on February 6, 1928, when the temperature in the early morning was 6° F. (26° below freezing). At noon, less than eight hours later, a worker appeared at the surface though the soil was still frozen. On February 25 a worker passed from one entrance to the other with a sharp wind blowing at 27° F., as recorded by a tested thermometer at one inch above the ground. The sun, however, induced a thaw, so that the temperature of the ground was really 33.5° F. Tests with honey enticed more of the workers out of doors till the surface cold had fallen to 30° F, when the surface of the soil was frozen and the ants brushed against hoarfrost around their entryway. Honey does not freeze at such a temperature and ants can still lap it up slowly.

“On cool, humid middays below 60° F. workers may remain active above ground all day, but seldom stay in the bright sun or on dry soil. They are at their best during or after cold rains, or a cold, humid period with overcast skies. They were most active outdoors between 35° and 55° F. all winter, but they occasionally crawled over the soil below 30° F. or above 60° F. One case of great activity occurred when a colony moved to a new site during a drizzle and kept excavating the new nest down into the subsoil with air-temperature about 60° F.

“For about five months these ants lived on dead or dying earthworms driven above ground by rains. If other food was available besides honey-dew or honey that had been stored in the crops of the repletes during the fall, I failed to discover it. I often saw imparis leave an earthworm that had been dried up by the sun and return to it as soon as another rain had soaked it up again.

“'Similar observations were made in regard to the winter activities of imparis at Jefferson City, Mo., during the winter of 1928-29. The ants were nesting in trodden, clayey, poorly drained loess soil. The workers were excavating December 14, 15 and 16, which were followed by a heavy freeze-up.”

Mr. Burrill's observations show that the ants do very little excavating during the winter but that this sets in suddenly a few days before the nuptial flight. This, as I have frequently noticed, takes place as early as the latter fortnight of March or the first fortnight of April. That the period must be much the same for the different varieties and over a considerable portion of the United States is indicated by the following dates of nuptial flights recorded in my notebooks, on the labels of mounted males and winged females or in the literature:

P. imparis (typical). Forest Hi11s, Mass., March 15 and 25; April 4, 5 and 6; Bridgetown, N.J., March 28; Albany, N.Y., March; Wauwatosa, Wis., April 20; Jefferson City, Mo., March 19, 20 and 21; Lawrence and Riley Co., Kansas, March, April 2.

var. testacea. Bronxville, N.Y., April 10; Plummer's Island, Maryland, Aprill2.

var. minuta. District of Columbia, April; Cape May, N.Y., March 24.

var. californica. Stanford University, Cal., Jan. 30, Feb. 23, and March 19.

The winged sexes that participate in the nuptial flights mature during the late summer of the previous year and are retained in the nests over winter. I have found males and winged females of the var. testacea at Lakehurst, N. J. in the nests on September 24. This retention of the sexual phases over winter occurs in a few of our other northern ants, e. g. in the various varieties of Camponotus herculeanus and of C. caryce, but in these cases the flight is later, usually in May or June, or even in July. The very early flight of imparis was first observed in Indiana by Say., who says: “They appeared in great numbers on the 2nd of April; the males swarmed around small bushes, alighting on the branches and leaves. The females were few.” I have seen such flights of the males about the Japanese barberry bushes in the Arnold Arboretum on fine days in late March and early April. The males dance up and down in rather compact swarms like the late summer swarms of male bees of the genus Chloralictus.

Both Burrill’s observations on its activity during the winter months and those on its very early nuptial flight indicate that P. imparis may be regarded as negatively thermotropic or adapted to cold.

Replete Workers

One characteristic of Prenopepis imparis colonies is the presence of workers with greatly extended gasters. These enlarged workers were once believed to be true repletes like those found in Myrmecocystus (Wheeler 1930a; Talbot 1943). However, Tschinkel (1987) determined that their enlarged state is actually caused by hypertrophied fat bodies and not the result of crop distention from retained liquid food.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis cornifoliae (a trophobiont) (Favret et al., 2010; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis fabae (a trophobiont) (Favret et al., 2010; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Capitophorus elaeagni (a trophobiont) (Favret et al., 2010; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Nearctaphis bakeri (a trophobiont) (Favret et al., 2010; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Rhopalosiphum maidis (a trophobiont) (Barton and Ives, 2014; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Uroleucon sonchellum (a trophobiont) (Favret et al., 2010; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a host for the fungus Laboulbenia formicarum (a parasite) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission within nest).

- This species is a host for the fungus Laboulbenia formicarum (a pathogen) (Espadaler & Santamaria, 2012).

Flight Period

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info.

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

- Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Life History Traits

- Queen number: polygynous (Frumhoff & Ward, 1992)

- Queen mating frequency: multiple (Frumhoff & Ward, 1992)

Castes

Williams and LaPolla (2016) - Microgynous queens were observed by Alex Wild (personal communication, September 9, 2015) in the Sierra Nevadas, California in October, 2001. Two specimens were collected by Wild, one of which was examined for this study (USNMENT00755072). The other can be found on www.AntWeb.org (CASENT0005430). These queens appear to be P. imparis, but are much smaller and were observed flying in the fall rather than early spring. While it is possible that this is an entirely new species, perhaps even an inquiline, based on its size, it is also possible that these individuals are microgynous (Rüppell & Heinze 1999) P. imparis queens. With only two specimens available and little morphological difference from P. imparis observed more evidence must be found in order to describe them as a new species.

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0102823. Photographer Jen Fogarty, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0103873. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0106035. Photographer Michael Branstetter, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by UCDC, Davis, CA, USA. |

Queen

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0005432. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by UCDC, Davis, CA, USA. |

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0104434. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

Male

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0104433. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0104863. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- imparis. Formica imparis Say, 1836: 287 (q.m.) U.S.A.

- Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 16 (w.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1953c: 142 (l.); Hauschteck, 1962: 219 (k.).

- Combination in Lasius: Roger, 1863b: 12.

- Combination in Prenolepis: Mayr, 1886d: 431.

- Status as species: Mayr, 1863: 416. Roger, 1863b: 12; Emery, 1893i: 635; Dalla Torre, 1893: 178; Ruzsky, 1905b: 262; Wheeler, W.M. 1916m: 591; Wheeler, W.M. 1917a: 523; Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 15 (redescription); Creighton, 1950a: 413; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1445; Bolton, 1995b: 364; Mackay & Mackay, 2002: 409; Coovert, 2005: 118; Ellison, et al. 2012: 220.

- Senior synonym of americana: Emery, 1893i: 635; Dalla Torre, 1893: 178.

- Senior synonym of wichita: Dalla Torre, 1893: 178; Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 15.

- Senior synonym of minuta, pumila, testacea: Creighton, 1950a: 414.

- Senior synonym of californica: Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1986g: 14.

- Senior synonym of arizonica, colimana, coloradensis, veracruzensis: Williams & LaPolla, 2016: 223.

- arizonica. Prenolepis imparis var. arizonica Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 22 (w.q.m.) U.S.A.

- Subspecies of imparis: Creighton, 1950a: 414; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1444; Bolton, 1995b: 363; Mackay & Mackay, 2002: 410.

- Junior synonym of imparis: Williams & LaPolla, 2016: 223.

- colimana. Prenolepis imparis var. colimana Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 24 (w.) MEXICO.

- Subspecies of imparis: Bolton, 1995b: 363.

- Junior synonym of imparis: Williams & LaPolla, 2016: 223.

- coloradensis. Prenolepis imparis var. coloradensis Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 22, fig. 4 (w.) U.S.A.

- Subspecies of imparis: Creighton, 1950a: 415; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1445; Bolton, 1995b: 363; Mackay & Mackay, 2002: 410.

- Junior synonym of imparis: Williams & LaPolla, 2016: 223.

- veracruzensis. Prenolepis imparis var. veracruzensis Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 24 (w.) MEXICO.

- Subspecies of imparis: Bolton, 1995b: 364.

- Junior synonym of imparis: Williams & LaPolla, 2016: 223.

- wichita. Formica (Tapinoma) wichita Buckley, 1866: 169 (w.) U.S.A.

- Combination in Prenolepis: Mayr, 1886d: 431.

- Junior synonym of nitens: Mayr, 1886d: 431.

- Junior synonym of imparis: Dalla Torre, 1893: 178; Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 15.

- americana. Prenolepis nitens var. americana Forel, 1891b: 94, pl. 3, fig. 4 (m.) U.S.A.

- Junior synonym of imparis: Emery, 1893i: 635; Dalla Torre, 1893: 178.

- minuta. Prenolepis imparis var. minuta Emery, 1893i: 636 (w.m.) U.S.A.

- Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 21 (q.).

- Subspecies of imparis: Wheeler, W.M. 1906b: 11; Wheeler, W.M. 1916m: 591; Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 21 (redescription).

- Junior synonym of imparis: Creighton, 1950a: 414.

- testacea. Prenolepis imparis var. testacea Emery, 1893i: 636 (q.m.) U.S.A.

- Wheeler, W.M. 1905f: 390 (w.).

- Subspecies of imparis: Wheeler, W.M. 1904e: 304; Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 20 (redescription).

- Junior synonym of imparis: Creighton, 1950a: 414.

- californica. Prenolepis imparis var. californica Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 23, fig. 4 (w.q.m.) U.S.A.

- Subspecies of imparis: Creighton, 1950a: 414; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1445.

- Junior synonym of imparis: Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1986g: 14.

- pumila. Prenolepis imparis var. pumila Wheeler, W.M. 1930b: 21 (w.m.) U.S.A.

- Junior synonym of imparis: Creighton, 1950a: 414.

Type Material

Williams and LaPolla (2016) - Syntype queen(s?) and male(s?), (no specific locality provided) (depository unknown) [not examined].

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Williams and LaPolla (2016) - (n=105): CMC: 16–18; EL: 0.23–0.33; EW: 0.19–0.24; HL: 0.74–0.98; HLA: 0.43–0.48; HLP: 0.25–0.34; HW: 0.71–0.98; IOD: 0.48–0.57; LF1: 0.22–0.29; LF2: 0.11–0.15; LHT: 1.01– 1.15; MMC: 1–5; MTW: 0.40–0.52; MW: 0.24–0.36; PDH: 0.28–0.39; PMC: 3–6; PrCL: 0.41–0.52; PrCW: 0.26– 0.33; PrFL: 0.78–0.98; PrFW: 0.17–0.21; PTH: 0.37–0.42; PTL: 0.33–0.40; PTW: 0.24–0.34; PW: 0.48–0.61; SL: 0.88–1.22; TL: 2.94–4.51; WF1: 0.06–0.09; WF2: 0.06–0.08; WL: 0.95–1.42; BLI: 122–153; CI: 90–101; EPI: 140–179; FLI: 185–208; HTI: 120–133; PetHI: 121–130; PetWI: 83–90; PrCI: 58–70; PrFI: 20–24; REL: 27–35; REL2: 28–36; REL3: 46–59; SI: 115–140.

Light to dark brown with head and gaster sometimes darker than mesosoma; entire cuticle smooth and shiny; abundant decumbent setae on scapes and legs; erect macrosetae on head, mesosoma, and gaster; head about as broad as long and square in shape with rounded posterolateral corners and a straight posterior margin; compound eyes moderately large and convex, but do not surpass the lateral margins of the head in full-face view; torulae overlap with the posterior border of the clypeus; anterior border of clypeus with a pair of prominent anterolateral lobes; mandibles with 5–7 teeth (usually 6) on the masticatory margin; ectal surface of mandibles with deep longitudinal striations; in profile view, propodeum is obtusely angled with a flat dorsal face; dorsal apex of petiole scale is sharply angled and forward-inclined.

Wheeler (1930) - Length 3-4 mm.

Head as broad as long, slightly narrower in front than behind, with straight posterior border and feebly rounded sides and posterior corners. Eyes moderately convex, nearly one-fourth as long as the sides of the head, and situated a little behind its middle. Mandibles rather flat, with •convex external borders, their apical borders feebly oblique, 6-toothed, the apical and basal tooth largest, the former strongly curved, the third tooth from the tip minute. Maxillary palpi very long, reaching to the occipital foramen. Clypeus convex in the middle, subcarinate behind, depressed on the sides, its anterior border broadly rounded and entire. Frontal area large but indistinctly defined; frontal groove absent; frontal carinae feeble, short and subparallel. Antennae slender; scapes extending about two-fifths their length beyond the posterior corners of the head; first funicular joint as long as the subequal second and third together; joints 2-8 nearly twice as long as broad, remaining joints somewhat shorter, except the last, which is as long as the two penutimate joints. Thorax small and slender, divided into two portions by a deep constriction of the posterior part of the mesonotum; the promesonotum somewhat longer than broad, evenly convex and subhemiopherical above, the dorsal outline not interrupted at the promesonotal suture, the mesonotum anteriorly as long as broad, subtrapezoidal, a little broader in front than behind, sloping downward and passing posteriorly into the constricted portion which bears on its dorsal surface the pair of somewhat projecting metathoracic spiracles close to the base of the epinotum. The latter is subrectangular from above and nearly as broad as long, in profile with subequal base and declivity, the former slightly convex and rising posteriorly where it has a faint longitudinal impression and forms a distinct but rounded angle with the declivity. This is broad and flat, with its projecting spiracles near the middle of its sides. Petiole as long as high, its node strongly inclined forward, in profile compressed and cuneate, with feebly convex anterior and posterior surfaces and rather acute border;• seen from behind it is trapezoidal, broader above than below, with straight sides and a transverse superior border, which is straight or very slightly concave in the middle. Gaster proportionally large, broad anteriorly, tapering behind to a point, convex above, the basal segment concave anteriorly where it overlies the petiole, its anterior border above straight and transverse in the middle and forming a distinct angle on each side. Legs rather slender.

Very smooth and shining; mandibles glossy, very finely longitudinally striate; head and thorax with small, sparse, piligerous punctures; gaster very finely, superficially and tranversely shagreened, with coarser piligerous punctures, and along the posterior borders of the segments with minute, hair-bearing tubercles.

Hairs and pubescence whitish or pale yellowish, the former rather coarse, erect or suberect, pointed, of unequal length, more abundant on the head and gaster than on the thorax, longest on the gaster. Cheeks, gula and front also with conspicuous short, sparse, appressed hairs, or very coarse pubescence. Antennae with abundant fine, oblique hairs or pubescence, longest and most conspicuous towards the tips of the scapes. Legs with very short, sparse, inconspicuous, appressed or subappressed pubescence.

Varying from pale castaneous to dark piceous brown, the thorax and anterior portion of the head usually paler, the gaster darker and more blackish; mandibles, antennae, legs, including coxae and posterior edges of gastric segments, brownish yellow or yellowish brown. Palpi pale yellow, mandibular teeth black.

Queen

Williams and LaPolla (2016) - (n=9): EL: 0.42–0.48; HL: 1.26–1.44; HW: 1.38–1.55; SL: 1.36–1.55; TL: 7.05–8.33; WL: 2.49–3.08; BLI: 175–199; CI: 105–117; REL: 31–38; REL2: 30–34; SI: 97–103. Much larger and distinctly lighter in color than male; light to medium brown; abundant short, erect macrosetae on head, mesosoma, and gaster; entire cuticle covered in dense pubescence; head broader than long and square in shape; three ocelli present; compound eyes large and convex, barely surpassing the lateral margins of the head in full-face view; antennae with 12 segments; scapes long, surpassing the posterior margin of the head; mandibles with 6 teeth on the masticatory margin; ectal surface of mandibles with longitudinal striations; mesosoma large to accommodate flight muscles and without a constriction; small collar-like pronotum; large and strongly convex shelf-like mesonotum; petiole is forward-inclined and triangular, as seen in worker; dorsal apex of petiole scale is sharply angled.

Wheeler (1930) - Length 7.5-8.5 mm.; wings 7-7.5 mm.

Head broader than long and more narrowed anteriorly than in the worker. Eyes rather large; ocelli small and close together. Thorax massive, broader than the head, from above broadly elliptical, dorsally somewhat flattened in profile; mesonotum as long as broad; scutellum large; epinotum small, subperpendicular, rounded, without base or declivity. Petiolar node broad, thick below, strongly anteroposteriorly compressed above, its superior border deeply excised in the middle. Gaster large, oblong-elliptical, its basal segment angulate on each side anteriorly as in the worker.

Less shining than the worker, with the mandibles more coarsely striate and the head, thorax and gaster much more densely punctate.

Erect hairs shorter and more numerous than in the worker. Head, thorax and gaster covered with yellowish appressed pubescence which, however, is not sufficiently dense to conceal the shining and punctate integument. A similar but somewhat shorter pubescence covers the antennae and legs.

Reddish brown; mandibles, antennae and legs slightly paler and more reddish. Wing membranes uniformly yellowish brown; veins and pterostigma resin-colored.

Male

Williams and LaPolla (2016) - (n=10): EL: 0.31–0.45; HL: 0.66–0.82; HW: 0.72–0.89; SL: 0.54–0.75; TL: 3.16–4.16; WL: 1.30–1.65; BLI: 165–191; CI: 102–110; REL: 47–57; REL2: 43–54; SI: 75–89.

Much smaller and distinctly darker than queen; dark brown; abundant long, erect macrosetae on head, mesosoma, and gaster; entire cuticle covered in dense pubescence; head broader than long and oval in shape; three large ocelli present; compound eyes very large and convex, surpassing the lateral margins of the head in full-face view; antennae with 13 segments; scapes very short, barely surpassing the posterior margin of the head; mandibles with a single apical tooth on the masticatory margin; ectal surface of mandibles with longitudinal striations; mesosoma large to accommodate flight muscles and without a constriction; small collar-like pronotum; large and strongly convex shelf-like mesonotum; petiole is forward-inclined and triangular, as seen in worker; dorsal apex of petiole scale is sharply angled; genitalia oriented ventrally; parameres elongate, roughly triangular, and curved medially; ectal surface of parameres flattened; digiti are long and slender and follow the penis valve as it curves ventrally; cuspi are broad, triangular, and very short relative to the rest of the genitalia; parameres are covered in dense very long, erect macrosetae; edges of cuspi are covered in short, erect macrosetae; 9th sternite is large and broad.

Wheeler (1930) - Length 3.5-4 mm.

Head, including the eyes, broader than long, broadly rounded behind, without posterior corners, narrowed anteriorly, with short, straight cheeks. Mandibles rather large and overlapping, but with only the apical tooth developed. Clypeus large, less convex than in the worker. Antennal scapes slender, about one-third as long as the long funiculus; first joint of the latter small, of the usual shape, about one and one-half times as long as broad; remaining joints broader, of uniform width, twice as long as broad, the penultimate joints somewhat shorter, the last as long as the two preceding joints together. Thorax not broader than the head; mesonotum convex anteriorly, distinctly broader than long; epinotum evenly rounded and sloping in profile, without distinct base and declivity. Petiolar node shaped somewhat as in the worker, but much thicker, inclined forward, with blunt apical border, straight and transverse but not impressed in the middle. Gaster elongate-elliptical; external genital appendages long, somewhat curved, uniformly tapering and blunt at the tip. Legs slender; hind tibiae feebly bent near the middle.

Shining and finely punctate; antennae and legs more finely and densely than the remainder of the body; mandibles very finely striate as in the worker.

Hairs grayish, rather soft and flexuous, long and abundant on the head and thorax and very conspicuous on the tip and venter of the gaster. Pubescence long, sparse and appressed, most distinct on the gaster, very fine and short on the legs, slightly longer and more oblique on the scapes.

Piceous black; antennae and mandibles dark brown; femora black, the trochanters, tips of femora, the tibiae and tarsi brownish yellow. Wings varying in color from whitish to grayish hyaline, with colorless or pale yellowish veins and pterostigma.

Karyotype

- 2n = 16 (Switzerland) (Hauschteck, 1962).

Etymology

Say described this ant from a queen and male in copula. The two sexes were quite different in color hence he named the species imparis.

Worker Morphology

Explore: Show all Worker Morphology data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Worker Morphology data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- Caste: monomorphic

References

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Baer, B. 2011. The copulation biology of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 14: 55-68.

- Borowiec, L. 2014. Catalogue of ants of Europe, the Mediterranean Basin and adjacent regions (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Genus (Wroclaw) 25(1-2): 1-340.

- Boudinot, B.E., Borowiec, M.L., Prebus, M.M. 2022. Phylogeny, evolution, and classification of the ant genus Lasius, the tribe Lasiini and the subfamily Formicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Systematic Entomology 47, 113-151 (doi:10.1111/syen.12522).

- Burford, B.P., Lee, G., Friedman, D.A., Brachmann, E., Khan, R., MacArthur-Waltz, D.J., McCarty, A.D., Gordon, D.M. 2018. Foraging behavior and locomotion of the invasive Argentine ant from winter aggregations. PLOS ONE 13, e0202117 (doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0202117).

- Carroll, T.M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). M.S. thesis, Purdue University.

- Cerda, X., Arnan, X., Retana, J. 2013. Is competition a significant hallmark of ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) ecology? Myrmecological News 18: 131-147.

- Chick, L.D., Lessard, J.-P., Dunn, R.R., Sanders, N.J. 2020. The coupled influence of thermal physiology and biotic interactions on the distribution and density of ant species along an elevational gradient. Diversity 12, 456 (doi:10.3390/d12120456).

- Cordonnier, M., Blight, O., Angulo, E., Courchamp, F. 2020. Behavioral data and analyses of competitive interactions between invasive and native ant species. Animals 10, 2451 (doi:10.3390/ani10122451).

- Creighton, W. S. 1950a. The ants of North America. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 104: 1-585 (page 414, Senior synonym of minuta, pumila and testaces)

- Csősz, S., Báthori, F., Gallé, L., Lőrinczi, G., Maák, I., Tartally, A., Kovács, É., Somogyi, A.Á., Markó, B. 2021. The myrmecofauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Hungary: Survey of ant species with an annotated synonymic inventory. Insects 16;12(1):78 (doi:10.3390/insects12010078).

- Csosz, S., Marko, B., Galle, L. 2011. The myrmecofauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Hungary: an updated checklist. North-Western Journal of Zoology 7: 55-62.

- Dalla Torre, K. W. von. 1893. Catalogus Hymenopterorum hucusque descriptorum systematicus et synonymicus. Vol. 7. Formicidae (Heterogyna). Leipzig: W. Engelmann, 289 pp. (page 178, Senior synonym of americana, Senior synonym of wichita)

- Davis, T. 2009. The ants of South Carolina (thesis, Clemson University).

- Emery, C. 1893k. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. Zool. Jahrb. Abt. Syst. Geogr. Biol. Tiere 7: 633-682 (page 635, Senior synonym of americana)

- Espadaler, X., Santamaria, S. 2012. Ecto- and Endoparasitic Fungi on Ants from the Holarctic Region. Psyche Article ID 168478, 10 pages (doi:10.1155/2012/168478).

- Fellers, J.H. 1989. Daily and seasonal activity in woodland ants. Oecologia 78: 69–76 (doi:10.1007/BF00377199).

- Hauschteck, E. 1962. Die Chromosomen einiger in der Schweiz vorkommender Ameisenarten. Vierteljahrsschr. Naturforsch. Ges. Zür. 107: 213-220 (page 219, karyotype described)

- Ipser, R.M., Brinkman, M.A., Gardner, W.A., Peeler, H.B. 2004. A survey of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Georgia. Florida Entomologist 87: 253-260.

- Ivanov, K. 2019. The ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): an updated checklist. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 70: 65–87 (doi:10.3897@jhr.70.35207).

- MacGown, J.A., Booher, D., Richter, H., Wetterer, J.K., Hill, J.G. 2021. An updated list of ants of Alabama (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with new state records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 147: 961-981 (doi:10.3157/061.147.0409).

- Mayr, G. 1886d. Die Formiciden der Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 36: 419-464 (page 431, Combination in Prenolepis)

- Miler, K., Turza, F. 2021. “O Sister, Where Art Thou?”—A review on rescue of imperiled individuals in ants. Biology 10, 1079 (doi:10.3390/biology10111079).

- Moura, M.N., Cardoso, D.C., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. The tight genome size of ants: diversity and evolution under ancestral state reconstruction and base composition. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa135 (doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa135).

- Perfilieva, K.S. 2021. Distribution and differentiation of fossil Oecophylla (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) species by wing imprints. Paleontological Journal 55(1), 76–89 (doi:10.1134/s003103012101010x).

- Rafiqi, A.M., Rajakumar, A., Abouheif, E. 2020. Origin and elaboration of a major evolutionary transition in individuality. Nature 585, 239–244. (doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2653-6).

- Rericha, L. 2007. Ants of Indiana. Indiana Department of Natural Resources, 51pp.

- Say, T. 1836. Descriptions of new species of North American Hymenoptera, and observations on some already described. Boston J. Nat. Hist. 1: 209-305 (page 287, queen, male described)

- Siddiqui, J. A., Li, J., Zou, X., Bodlah, I., Huang, X. 2019. Meta-analysis of the global diversity and spatial patterns of aphid-ant mutualistic relationships. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 17: 5471-5524 (doi:10.15666/aeer/1703_54715524).

- Tschinkel, W.R. 1987. Seasonal life history and nest architecture of a winter-active ant, Prenolepis imparis. Insectes Sociaux 34 (3): 143–164 (doi:10.1007/bf02224081).

- Tschinkel, W.R. 2015. The architecture of subterranean ant nests: beauty and mystery underfoot. Journal of Bioeconomics 17:271–291 (DOI 10.1007/s10818-015-9203-6).

- Warren II, R.J., Bayba, S., Krupp, K.T. 2018. Interacting effects of urbanization and coastal gradients on ant thermal responses. Journal of Urban Ecology 4: 1-11 (doi:10.1093/jue/juy026).

- Warren, R.J., Chick, L. 2013. Upward ant distribution shift corresponds with minimum, not maximum, temperature tolerance. Global Change Biology 19, 2082–2088 (doi:10.1111/GCB.12169).

- Warren, R.J., Elliott, K.J., Giladi, I., King, J.R., Bradford, M.A. 2019. Field experiments show contradictory short- and long-term myrmecochorous plant impacts on seed-dispersing ants. Ecological Entomology 44, 30–39 (doi:10.1111/EEN.12666).

- Waters, J.S., Keough, N.W., Burt, J., Eckel, J.D., Hutchinson, T., Ewanchuk, J., Rock, M., Markert, J.A., Axen, H.J., Gregg, D. 2022. Survey of ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in the city of Providence (Rhode Island, United States) and a new northern-most record for Brachyponera chinensis (Emery, 1895). Check List 18(6), 1347–1368 (doi:10.15560/18.6.1347).

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1953c. The ant larvae of the subfamily Formicinae. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 46: 126-171 (page 142, larva described)

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1986g. The ants of Nevada. Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, vii + 138 pp. (page 14, Senior synonym of californica)

- Wheeler, W.M. 1930. The ant Prenolepis imparis Say. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 23, 1-26.

- Williams, J. L. and J. S. LaPolla. 2016. Taxonomic revision and phylogeny of the ant genus Prenolepis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). 4200(2):201–258. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4200.2.1

- Williams, J.L. 2022. Description of Prenolepis rinpoche sp. nov. from Nepal, with discussion of Asian Prenolepis species biogeography. Asian Myrmecology 15, e015008 (doi:10.20362/am.015008).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Adams T. A., W. J. Staubus, and W. M. Meyer. 2018. Fire impacts on ant assemblages in California sage scrub. Southwestern Entomologist 43(2): 323-334.

- Annotated Ant Species List Ordway-Swisher Biological Station. Downloaded at http://ordway-swisher.ufl.edu/species/os-hymenoptera.htm on 5th Oct 2010.

- Backlin, Adam R., Sara L. Compton, Zsolt B. Kahancza and Robert N. Fisher. 2005. Baseline Biodiversity Survey for Santa Catalina Island. Catalina Island Conservancy. 1-45.

- Banschbach V. S., and E. Ogilvy. 2014. Long-term Impacts of Controlled Burns on the Ant Community (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of a Sandplain Forest in Vermont. Northeastern Naturalist 21(1): 1-12.

- Boulton A. M., Davies K. F. and Ward P. S. 2005. Species richness, abundance, and composition of ground-dwelling ants in northern California grasslands: role of plants, soil, and grazing. Environmental Entomology 34: 96-104

- Campbell J. W., S. M. Grodsky, D. A. Halbritter, P. A. Vigueira, C. C. Vigueira, O. Keller, and C. H. Greenberg. 2019. Asian needle ant (Brachyponera chinensis) and woodland ant responses to repeated applications of fuel reduction methods. Ecosphere 10(1): e02547.

- Campbell K. U., and T. O. Crist. 2017. Ant species assembly in constructed grasslands isstructured at patch and landscape levels. Insect Conservation and Diversity doi: 10.1111/icad.12215

- Canadensys Database. Dowloaded on 5th February 2014 at http://www.canadensys.net/

- Carroll T. M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Master's thesis Purdue University.

- Castano-Meneses, G., M. Vasquez-Bolanos, J. L. Navarrete-Heredia, G. A. Quiroz-Rocha, and I. Alcala-Martinez. 2015. Avances de Formicidae de Mexico. Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

- Clark A. T., J. J. Rykken, and B. D. Farrell. 2011. The Effects of Biogeography on Ant Diversity and Activity on the Boston Harbor Islands, Massachusetts, U.S.A. PloS One 6(11): 1-13.

- Clark Adam. Personal communication on November 25th 2013.

- Cokendolpher J. C., and O. F. Francke. 1990. The ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of western Texas. Part II. Subfamilies Ecitoninae, Ponerinae, Pseudomyrmecinae, Dolichoderinae, and Formicinae. Special Publications, the Museum. Texas Tech University 30:1-76.

- Cole A. C. 1940. A Guide to the Ants of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee. American Midland Naturalist 24(1): 1-88.

- Cole A. C. 1953. A checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee. Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science. 28: 34-35.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1949. The ants of Mountain Lake, Virginia. Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science 24: 155-156.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1954. Studies of New Mexico ants. XII. The genera Brachymyrmex, Camponotus, and Prenolepis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science 29: 271-272.

- Coovert G. A. 2005. The Ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ohio Biological Survey, Inc. 15(2): 1-207.

- Coovert, G.A. 2005. The Ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Ohio Biological Survey Bulletin New Series Volume 15(2):1-196

- Cover S. P., and R. A. Johnson. 20011. Checklist of Arizona Ants. Downloaded on January 7th at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/AZants-2011%20updatev2.pdf

- Dash S. T. and L. M. Hooper-Bui. 2008. Species diversity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Louisiana. Conservation Biology and Biodiversity. 101: 1056-1066

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Davis W. T., and J. Bequaert. 1922. An annoted list of the ants of Staten Island and Long Island, N. Y. Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological Society 17(1): 1-25.

- Del Toro I., K. Towle, D. N. Morrison, and S. L. Pelini. 2013. Community Structure, Ecological and Behavioral Traits of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Massachusetts Open and Forested Habitats. Northeastern Naturalist 20: 1-12.

- Del Toro, I. 2010. PERSONAL COMMUNICATION. MUSEUM RECORDS COLLATED BY ISRAEL DEL TORO

- Des Lauriers J., and D. Ikeda. 2017. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the San Gabriel Mountains of Southern California, USA with an annotated list. In: Reynolds R. E. (Ed.) Desert Studies Symposium. California State University Desert Studies Consortium, 342 pp. Pages 264-277.

- Deyrup M. 1998. Smithistruma memorialis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), a new species of ant from the Kentucky Cumberland Plateau. Entomological News 109: 81-87.

- Deyrup M., C. Johnson, G. C. Wheeler, J. Wheeler. 1989. A preliminary list of the ants of Florida. Florida Entomologist 72: 91-101

- Deyrup, M. 2003. An updated list of Florida ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Florida Entomologist 86(1):43-48.

- DuBois M. B. 1981. New records of ants in Kansas, III. State Biological Survey of Kansas. Technical Publications 10: 32-44

- Dubois, M.B. and W.E. Laberge. 1988. An Annotated list of the ants of Illionois. pages 133-156 in Advances in Myrmecology, J. Trager

- Eastlake Chew A. and Chew R. M. 1980. Body size as a determinant of small-scale distributions of ants in evergreen woodland southeastern Arizona. Insectes Sociaux 27: 189-202

- Ellison A. M. 2012. The Ants of Nantucket: Unexpectedly High Biodiversity in an Anthropogenic Landscape. Northeastern Naturalist 19(1): 43-66.

- Ellison A. M., S. Record, A. Arguello, and N. J. Gotelli. 2007. Rapid Inventory of the Ant Assemblage in a Temperate Hardwood Forest: Species Composition and Assessment of Sampling Methods. Environ. Entomol. 36(4): 766-775.

- Ellison A. M., and E. J. Farnsworth. 2014. Targeted sampling increases knowledge and improves estimates of ant species richness in Rhode Island. Northeastern Naturalist 21(1): NENHC-13NENHC-24.

- Emery C. 1893. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Tiere 7: 633-682.

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Fisher B. L. 1997. A comparison of ant assemblages (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) on serpentine and non-serpentine soils in northern California. Insectes Sociaux 44: 23-33

- Fisher, B.L. 1997. A comparison of ant assemblages (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) on serpentine and non-serpentine soils in northern California. Insectes Sociaux 44:23-33.

- Forster J.A. 2005. The Ants (hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Alabama. Master of Science, Auburn University. 242 pages.

- Frye J. A., T. Frye, and T. W. Suman. 2014. The ant fauna of inland sand dune communities in Worcester County, Maryland. Northeastern Naturalist, 21(3): 446-471.

- General D. M., and L. C. Thompson. 2011. New Distributional Records of Ants in Arkansas for 2009 and 2010 with Comments on Previous Records. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 65: 166-168.

- General D., and L. Thompson. 2008. Ants of Arkansas Post National Memorial: How and Where Collected. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 62: 52-60.

- General D.M. & Thompson L.C. 2007. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Arkansas Post National Memorial. Journal of the Arkansas Acaedemy of Science. 61: 59-64

- General D.M. & Thompson L.C. 2008. New Distributional Records of Ants in Arkansas for 2008. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science. 63: 182-184

- Gibbs M. M., P. L. Lambdin, J. F. Grant, and A. M. Saxton. 2003. Ground-inhabiting ants collected in a mixed hardwood southern Appalachian forest in Eastern Tennessee. Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science 78(2): 45-49.

- Gotelli, N.J. and A.M. Ellison. 2002. Biogeography at a Regional Scale: Determinants of Ant Species Density in New England Bogs and Forests. Ecology 83(6):1604-1609

- Graham, J.H., A.J. Krzysik, D.A. Kovacic, J.J. Duda, D.C. Freeman, J.M. Emlen, J.C. Zak, W.R. Long, M.P. Wallace, C. Chamberlin-Graham, J.P. Nutter and H.E. Balbach. 2008. Ant Community Composition across a Gradient of Disturbed Military Landscapes at Fort Benning, Georgia. Southeastern Naturalist 7(3):429-448

- Greenberg L., M. Martinez, A. Tilzer, K. Nelson, S. Koening, and R. Cummings. 2015. Comparison of different protocols for control of the Red Imported Fire Ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), in Orange County, California, including a list of co-occurring ants. Southwestern Entomologist 40(2): 297-305.

- Gregg R. E. 1945 (1944). The ants of the Chicago region. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 37: 447-480

- Grodsky S. M., J. W. Campbell, S. R. Fritts, T. B. Wigley, and C. E. Moorman. 2018. Variable responses of non-native and native ants to coarse woody debris removal following forest bioenergy harvests. Forest Ecology and Management doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.02.010

- Guénard B., K. A. Mccaffrey, A. Lucky, and R. R. Dunn. 2012. Ants of North Carolina: an updated list (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 3552: 1-36.

- Hayes W. P. 1925. A preliminary list of the ants of Kansas (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). [concl.]. Entomological News 36: 69-73

- Headley A. E. 1943. The ants of Ashtabula County, Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). The Ohio Journal of Science 43(1): 22-31.

- Heithaus R. E., and M. Humes. 2003. Variation in Communities of Seed-Dispersing Ants in Habitats with Different Disturbance in Knox County, Ohio. OHIO J. SCI. 103 (4): 89-97.

- Hess C. G. 1958. The ants of Dallas County, Texas, and their nesting sites; with particular reference to soil texture as an ecological factor. Field and Laboratory 26: 3-72.

- Hill J.G. & Brown R. L. 2010. The Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Fauna of Black Belt Prairie Remnants in Alabama and Mississippi. Southeastern Naturalist. 9: 73-84

- Holway D.A. 1998. Effect of Argentine ant invasions on ground-dwelling arthropods in northern California riparian woodlands. Oecologia. 116: 252-258

- Ipser R. M. 2004. Native and exotic ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Georgia: Ecological Relationships with implications for development of biologically-based management strategies. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, University of Georgia. 165 pages.

- Ivanov, K. 2019. The ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): an updated checklist. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 70: 65–87.

- Ivanov K., L. Hightower, S. T. Dash, and J. B. Keiper. 2019. 150 years in the making: first comprehensive list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Virginia, USA. Zootaxa 4554 (2): 532–560.

- Ivanov K., and J. Keiper. 2009. Effectiveness and Biases of Winkler Litter Extraction and Pitfall Trapping for Collecting Ground-Dwelling Ants in Northern Temperate Forests. Environ. Entomol. 38(6): 1724-1736.

- Jeanne R. J. 1979. A latitudinal gradient in rates of ant predation. Ecology 60(6): 1211-1224.

- Johnson C. 1986. A north Florida ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insecta Mundi 1: 243-246

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Johnson, R.A. and P.S. Ward. 2002. Biogeography and endemism of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Baja California, Mexico: a first overview. Journal of Biogeography 29:10091026/

- Jusino-Atresino R., and S. A. Phillips, Jr. 1992. New ant records for Taylor Co., Texas. The Southern Naturalist 34(4): 430-433.

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Kjar D. 2009. The ant community of a riparian forest in the Dyke Marsh Preserve, Fairfax County, Virginiam and a checklist of Mid-Atlantic Formicidae. Banisteria 33: 3-17.

- Kjar D., and E. M. Barrows. 2004. Arthropod community heterogeneity in a mid-Atlantic forest highly invaded by alien organisms. Banisteria 23: 26-37.

- Kjar D., and Z. Park. 2016. Increased ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) incidence and richness are associated with alien plant cover in a small mid-Atlantic riparian forest. Myrmecological News 22: 109-117.

- Lessard J. P., R. R. Dunn, C. R. Parker, and N. J. Sanders. 2007. Rarity and Diversity in Forest Ant Assemblages of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Southeastern Naturalist 1: 215-228.

- Lessard, J.-P., R. R. Dunn and N. J. Sanders. 2009. Temperature-mediated coexistence in temperate forest ant communities. Insectes Sociaux 56(2):149-456.

- Lynch J. F. 1981. Seasonal, successional, and vertical segregation in a Maryland ant community. Oikos 37: 183-198.

- Lynch J. F. 1988. An annotated checklist and key to the species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Chesapeake Bay region. The Maryland Naturalist 31: 61-106

- Lynch J. F., and A. K. Johnson. 1988. Spatial and temporal variation in the abundance and diversity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the soild and litter layers of a Maryland forest. American Midland Naturalist 119(1): 31-44.

- MacGown J. A., J. G. Hill, L. C. Majure, and J. L. Seltzer. 2008. Rediscovery of Pogonomyrmex badius(Latreille) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Mainland Mississippi, with an Analysis of Associated Seeds and Vegetation. Midsouth Entomologist 1: 17-28.

- MacGown J. A., J. G. Hill, R. L. Brown, T. L. Schiefer, J. G. Lewis. 2012. Ant diversity at Noxubee National Wildlife Refuge in Oktibbeha, Noxubee, and Winston Counties, Mississippi. Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station Bulletin 1197: 1-30

- MacGown J. A., J. G. Hill, and R. L. Brown. 2010. Native and exotic ant in Mississippi state parks. Proceedings: Imported Fire Ant Conference, Charleston, South Carolina, March 24-26, 2008: 74-80.

- MacGown J. A., and R. L. Brown. 2006. Survey of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Tombigbee National Forest in Mississippi. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 79(4):325-340.

- MacGown J.A., Hill J.G. and Skvarla M. 2011. New Records of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) for Arkansas with a Synopsis of Previous Records. Midsouth Entomologist. 4: 29-38

- MacGown, J. and J.G. Hill. Ants collected at Palestinean Gardens, George County Mississippi.

- MacGown, J.A and J.A. Forster. 2005. A preliminary list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Alabama, U.S.A. Entomological News 116(2):61-74

- MacGown, J.A. and JV.G. Hill. Ants of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Tennessee and North Carolina).

- MacGown, J.A. and R.L. Brown. 2006. Observations on the High Diversity of Native Ant Species Coexisting with Imported Fire Ants at a Microspatial Scale in Mississippi. Southeastern Naturalist 5(4):573-586

- MacGown, J.A. and R.L. Brown. 2006. Survey of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Tombigbee National Forest in Mississippi. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 79(4):325-340.

- MacGown, J.A., J.G. Hill, R.L. Brown and T.L. 2009. Ant Diversity at Noxubee National Wildlife Refuge in Oktibbeha, Noxubee, and Winston Counties, Mississippi Report #2009-01. Schiefer. 2009.

- MacGown. J. 2011. Ants collected during the 25th Annual Cross Expedition at Tims Ford State Park, Franklin County, Tennessee

- Macgown J. A., S. Y. Wang, J. G. Hill, and R. J. Whitehouse. 2017. A List of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Collected During the 2017 William H. Cross Expedition to the Ouachita Mountains of Arkansas with New State Records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society, 143(4): 735-740.

- Mackay W. P., and E. E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 400 pp.

- Mahon M. B., K. U. Campbell, and T. O. Crist. 2017. Effectiveness of Winkler litter extraction and pitfall traps in sampling ant communities and functional groups in a temperate forest. Environmental Entomology 46(3): 470–479.

- Mallis A. 1941. A list of the ants of California with notes on their habits and distribution. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 40: 61-100.

- Martelli, M.G., M.M. Ward and Ann M. Fraser. 2004. Ant Diversity Sampling on the Southern Cumberland Plateau: A Comparison of Litter Sifting and Pitfall Trapping. Southeastern Naturalist 3(1): 113-126

- Matsuda T., G. Turschak, C. Brehme, C. Rochester, M. Mitrovich, and R. Fisher. 2011. Effects of Large-Scale Wildfires on Ground Foraging Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Southern California. Environmental Entomology 40(2): 204-216.

- Menke S. B., E. Gaulke, A. Hamel, and N. Vachter. 2015. The effects of restoration age and prescribed burns on grassland ant community structure. Environmental Entomology http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvv110

- Menke S. B., and N. Vachter. 2014. A comparison of the effectiveness of pitfall traps and winkler litter samples for characterization of terrestrial ant (Formicidae) communities in temperate savannas. The Great Lakes Entomologist 47(3-4): 149-165.

- Menzel T. O., and T. E. Nebeker. 2008. Distribution of Hybrid Imported Fire Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and Some Native Ant Species in Relation to Local Environmental Conditions and Interspecific Competition in Mississippi Forests. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 101(1): 119-127.

- Newman L. M. and R. J. Wolff. 1990. Ants of a northern Illinois Savanna and degraded savanna woodland. Procedings of the twelfth north american prairie conference. Page 71-74

- Nuhn, T.P. and C.G. Wright. 1979. An Ecological Survey of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a Landscaped Suburban Habitat. American Midland Naturalist 102(2):353-362

- O'Keefe S. T., J. L. Cook, T. Dudek, D. F. Wunneburger, M. D. Guzman, R. N. Coulson, and S. B. Vinson. 2000. The Distribution of Texas Ants. The Southwestern Entomologist 22: 1-92.

- O'Neill J.C. and Dowling A.P.G. 2011. A Survey of the Ants (hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Arkansas and the Ozark Mountains. An Undergraduate Honors, University of Arkansas. 18pages.

- Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture Collection (Pers. Comm. Sven-Erik Spichiger 23 Dec 2017)

- Ratchford, J.S., S.E. Wittman, E.S. Jules, A.M. Ellison, N.J. Gotelli and N.J. Sanders. 2005. The effects of fire, local environment and time on ant assemblages in fens and forests. Diversity and Distributions 11:487-497.

- Reddell J. R., and J. C. Cokendolpher. 2001. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from caves of Belize, Mexico, and California and Texas (U.S.A.) Texas. Texas Memorial Museum Speleological Monographs 5: 129-154.

- Roeder K. A., and D. V. Roeder. 2016. A checklist and assemblage comparison of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma. Check List 12(4): 1935.

- Rowles, A.D. and J. Silverman. 2009. Carbohydrate supply limits invasion of natural communities by Argentine ants. Oecologia 161(1):161-171

- Sanchez-Pena S. R. 2013. House Infestation and Outdoor Winter Foraging by the Winter Ant, Prenolepis imparis Say (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), in Saltillo, Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist 38(2): 357-360.

- Smith M. R. 1934. A list of the ants of South Carolina. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 42: 353-361.

- Smith M. R. 1935. A list of the ants of Oklahoma (Hymen.: Formicidae) (continued from page 241). Entomological News 46: 261-264.

- Stahlschmidt Z. R., and D. Johnson. 2018. Moving targets: determinants of nutritional preferences and habitat use in an urban ant community. Urban Ecosystems 21: 1151–1158.

- Staubus W. J., E. S. Boyd, T. A. Adams, D. M. Spear, M. M. Dipman, W. M. Meyer III. 2015. Ant communities in native sage scrub, non-native grassland, and suburban habitats in Los Angeles County, USA: conservation implications. Journal of Insect Conservervation 19:669–680

- Sturtevant A. H. 1931. Ants collected on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Psyche (Cambridge) 38: 73-79

- Talbot M. 1957. Populations of ants in a Missouri woodland. Insectes Sociaux 4(4): 375-384.

- Talbot M. 1976. A list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Edwin S. George Reserve, Livingston County, Michigan. Great Lakes Entomologist 8: 245-246.

- Toennisson T. A., N. J. Sanders, W. E. Klingeman, and K. M. Vail. 2011. Influences on the Structure of Suburban Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Communities and the Abundance of Tapinoma sessile. Environ. Entomol. 40(6): 1397-1404.

- Trager, J. and C.Johnson. 1985. A slave-making ant in Florida: Polyergus lucidus with observations on the natural history of its host Formica archboldi (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). The Florida Entomologist 68(2):261-266.

- Van Pelt A. F. 1948. A Preliminary Key to the Worker Ants of Alachua County, Florida. The Florida Entomologist 30(4): 57-67

- Van Pelt A. F. 1966. Activity and density of old-field ants of the Savannah River Plant, South Carolina. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 82: 35-43.

- Van Pelt A., and J. B. Gentry. 1985. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Savannah River Plant, South Carolina. Dept. Energy, Savannah River Ecology Lab., Aiken, SC., Report SRO-NERP-14, 56 p.

- Van Pelt, A. 1983. Ants of the Chisos Mountains, Texas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) . Southwestern Naturalist 28:137-142.

- Varela-Hernandez, F., M. Rocha-Ortega, W. P. Mackay, and R. W. Jones. 2016. Lista preliminar de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del estado de Queretaro, Mexico. Pages 429-435 in . W. Jones., and V. Serrano-Cardenas, editors. Historia Natural de Queretaro. Universidad Autonoma de Queretaro, Mexico.

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Wang C., J. Strazanac and L. Butler. 2000. Abundance, diversity and activity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in oak-dominated mixed Appalachian forests treated with microbial pesticides. Environmental Entomology. 29: 579-586

- Ward P. S. 1987. Distribution of the introduced Argentine ant (Iridomyrmex humilis) in natural habitats of the lower Sacramento Valley and its effects on the indigenous ant fauna. Hilgardia 55: 1-16

- Warren, L.O. and E.P. Rouse. 1969. The Ants of Arkansas. Bulletin of the Agricultural Experiment Station 742:1-67

- Wenner A. M. 1959. The ants of Bidwell Park, Chico, California. American Midland Naturalist 62: 174-183

- Wetterer, J. K.; Ward, P. S.; Wetterer, A. L.; Longino, J. T.; Trager, J. C.; Miller, S. E. 2000. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Santa Cruz Island, California. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 99:25-31.

- Wetterer, J.K., P.S. Ward, A.L. Wetterer, J.T. Longino, J.C. Trager and S.E. Miller. 2000. Ants (Hymenoptera:Formicidae) of Santa Cruz Island, California. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Science 99(1):25-31.

- Wheeler G. C., J. N. Wheeler, and P. B. Kannowski. 1994. Checklist of the ants of Michigan (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). The Great Lakes Entomologist 26(4): 297-310

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler J. 1989. A checklist of the ants of Oklahoma. Prairie Naturalist 21: 203-210.

- Wheeler W. M. 1905. An annotated list of the ants of New Jersey. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 21: 371-403.

- Wheeler W. M. 1906. Fauna of New England. 7. List of the Formicidae. Occasional Papers of the Boston Society of Natural History 7: 1-24.

- Wheeler W. M. 1913. Ants collected in Georgia by Dr. J. C. Bradley and Mr. W. T. Davis. Psyche (Cambridge) 20: 112-117.

- Wheeler W. M. 1917. The mountain ants of western North America. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 52: 457-569.

- Wheeler W. M. 1930. The ant Prenolepis imparis Say. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 23: 1-26.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1985. A checklist of Texas ants. Prairie Naturalist 17:49-64.

- Wheeler, G.C., J. Wheeler and P.B. Kannowski. 1994. CHECKLIST OF THE ANTS OF MICHIGAN (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE). Great Lakes Entomologist 26:1:297-310

- Whitcomb W. H., H. A. Denmark, A. P. Bhatkar, and G. L. Greene. 1972. Preliminary studies on the ants of Florida soybean fields. Florida Entomologist 55: 129-142.

- Williams J. L., and J. S. LaPolla. 2016. Taxonomic revision and phylogeny of the ant genus Prenolepis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 4200: 201-258.

- Yitbarek S., J. H. Vandermeer, and D. Allen. 2011. The Combined Effects of Exogenous and Endogenous Variability on the Spatial Distribution of Ant Communities in a Forested Ecosystem (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Environ. Entomol. 40(5): 1067-1073.

- Young J., and D. E. Howell. 1964. Ants of Oklahoma. Miscellaneous Publication. Oklahoma Agricultural Experimental Station 71: 1-42.

- Young, J. and D.E. Howell. 1964. Ants of Oklahoma. Miscellaneous Publications of Oklahoma State University MP-71

- Zettler J. A., M. D. Taylor, C. R. Allen, and T. P. Spira. 2004. Consequences of Forest Clear-Cuts for Native and Nonindigenous Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 97(3): 513-518.

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Polygynous

- Replete Workers

- Photo Gallery

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- Tropical

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Aphis cornifoliae

- Host of Aphis fabae

- Host of Capitophorus elaeagni

- Host of Nearctaphis bakeri

- Host of Rhopalosiphum maidis

- Host of Uroleucon sonchellum

- Fungus Associate

- Host of Laboulbenia formicarum

- FlightMonth

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Formicinae

- Lasiini

- Prenolepis

- Prenolepis imparis

- Formicinae species

- Lasiini species

- Prenolepis species

- Ssr