Mycetomoellerius kempfi

| Mycetomoellerius kempfi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycetomoellerius |

| Species: | M. kempfi |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycetomoellerius kempfi (Fowler, 1982) | |

Fowler (1982) commented briefly that nests of M. kempfi consist of small tumulus of excavated soil, with one entrance and that he observed workers foraging on fresh leguminous vegetation. (Mayhe-Nunes and Brandão 2005)

Identification

A member of the Iheringi species group. Mayhe-Nunes and Brandão (2005) - This species resembles Mycetomoellerius iheringi (see discussion), as reported by Fowler (1982), but good distinctive characters are the lobes on antennal scapes pointing outwards and the abundant, long and flexuous pilosity of the body. Kempf labeled specimens that belong to this taxon with a name meaning a Trachymyrmex (the genus it was originally described as belonging to) with long hairs in Latin. Indeed, all specimens of M. kempfi show long, flexuous decumbent hairs all over the body as mentioned above.

In comparison with type-locality samples, some Sao Paulo specimens have the projections on the declivous face of mesonotum and dorsum of petiole vestigial or absent.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: -17.45404° to -31.648611°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

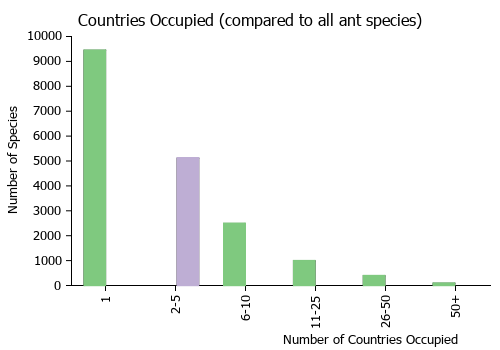

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Castes

Phylogeny

| Mycetomoellerius |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Based on Micolino et al., 2020 (selected species only).

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- kempfi. Trachymyrmex kempfi Fowler, 1982: 70, figs. 1-3 (w.) PARAGUAY.

- Combination in Mycetomoellerius: Solomon et al., 2019: 948.

- See also: Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão, 2005: 290.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Mayhe-Nunes and Brandão (2005) - TL 3.8-4.2; HL 1.02-1.14; HW 0.95-1.03; IFW 0.65-0.68; ScL 0.73-0.89; TrL 1.49-1.67; Hfl 1.35-1.42. Reddish yellow to reddish brown, with darker postpetiole and gaster in some specimens. Integuement fine and indistinctly shagreened, opaque. Body and appendages clothed with moderately long and oblique to decumbent hairs; scarce strongly curved short hairs confined to some parts of postpetiole and gaster.

Head in full face view little longer than broad (CI 95). Mandible smooth and shining except laterally on base, where it is finely transversely striate, and near the masticatory margin, which bears the apical, and 6 regularly developed teeth. Frontal lobe sub-triangular, moderately expanded laterad (FLI66); anterior border evenly concave; posterior border slightly convex. Frontal carina diverging cuadad, fading out a little before the apex of scrobe. Front and vertex without longitudinal rugulae, with minute isolated piligerous tubercles. Posterior third of antennal scrobe vestigially delimited. Supraocular projection vestigial. Occipital corner rounded in full-face view, with many small piligerous tubercles. Occiput slightly notched in middle. Occipital tooth developed as a stout spine-like projection rather smooth. Inferior occipital corner indistinctly emarginated with weak carina. Eye almost flat, no more than 14 facets in a row across the greatest diameter. Antennal scape slighty surpassing the occipital corner, when laid back over the head as much as possible; basal lobe perpendicularly enlarged, its outer projection bigger than the internal ones, outwards directed when the scape is lodged in the scrobe; anterior surface surmounted by small tubercles.

Alitrunk. Pronotum with an indistinct humeral angle; antero-inferior corner armed with a triangular and flattened spine-like projection; lateral spines moderately long; median projections as two small microtuberculated spines. Mesonotum with the first pair of projections a little stouter and longer than pronotal lateral spines; second pair very low, formed by a small and crenulated longitudinal ridge, sometimes vestigial; third pair vestigial or absent. Mesopleura covered with hairs; acute triangular projection on superior border of katepisternum. Alitrunk weakly constricted dorso-laterally at the shallowly impressed metanotal groove. Basal face of propodeum narrow, laterally delimited by a row of small teeth; propodeal spines longer and slender than promesonotal projections.

Waist and gaster. Petiole shortly pedunculated, the node proper as long as broad, with one or two pairs of minute dorsal teeth; subpetiolar process vestigial. Postpetiole slightly broader than long, shallowly excavate above; postero-dorsal border straight; posterolateral corners without projections. Gaster opaque with minute piligerous tubercles randomly distributed in the tergum 1.

Type Material

Mayhe-Nunes and Brandão (2005) - Workers, holotype and 18 paratypes. Paraguay, Nueva Assuncion: Teniente Enciso [21° 00'S 61° 00' W] (Museum of Comparative Zoology, National Museum of Natural History; Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History; not examined).

Alex Wild collected a sample in Paraguay, compared it with types (deposited in LACM, and not as stated by Fowler although we are not sure whether the collections mentioned by Fowler keep other types) and kindly sent us two workers for deposit in the MZSP. Afterwards, we found an undetermined sample in the MZSP that we recognize as T. kempfi, with a handwritten label by Kempf with very similar data to the type material: Paraguay, Tte. Enciso 1975 HF xiv, H. Fowler, # 13414; although they do not belong to the type series, probably belong to the series used by Fowler in the original description.

References

- Fowler, H. G. 1982a. A new species of Trachymyrmex fungus-growing ant (Hymenoptera: Myrmicinae: Attini) from Paraguay. J. N. Y. Entomol. Soc. 90: 70-73 (page 70, figs. 1-3 worker described)

- Mayhé-Nunes, A. J. and Brandão, C. R. F. 2005. Revisionary studies on the attine ant genus Trachymyrmex Forel. Part 2: the Iheringi group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology. 45(2):271-305. (page 290, figs. 29-32 worker described)

- Solomon, S.E., Rabeling, C., Sosa-Calvo, J., Lopes, C.T., Rodrigues, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci Jr, M., Mueller, U.G., Schultz, T.R. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939-956 (doi:10.1111/syen.12370).

- Tibcherani, M., Aranda, R., Mello, R.L. 2020. Time to go home: The temporal threshold in the regeneration of the ant community in the Brazilian savanna. Applied Soil Ecology 150, 103451 (doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.103451).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Brandao, C.R.F. 1991. Adendos ao catalogo abreviado das formigas da regiao neotropical (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Rev. Bras. Entomol. 35: 319-412.

- Drose W., L. R. Podgaiski, A. Cavalleri, R. M. Feitosa, and M. S. Mendonca. 2017. Ground-dwelling and vegetation ant fauna in southern Brazilian grasslands. Sociobiology 64(4): 381-392.

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Fowler H. G. 1982. A new species of Trachymyrmex fungus-growing ant (Hymenoptera: Myrmicinae: Attini) from Paraguay. J. N. Y. Entomol. Soc. 90: 70-73.

- Mayhé-Nunes A. J., and C. R. F. Brandão. 2005. Revisionary studies on the attine ant genus Trachymyrmex Forel. Part 2: the Iheringi group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 45(2): 271-305.

- Solomon S. E., C. Rabeling, J. Sosa-Calvo, C. Lopes, A. Rodrigues, H. L. Vasconcelos, M. Bacci, U. G. Mueller, and T. R. Schultz. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939–956.