Mycetomoellerius relictus

| Mycetomoellerius relictus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycetomoellerius |

| Species: | M. relictus |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycetomoellerius relictus (Borgmeier, 1934) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Found in both forest habitats and in open fields.

Identification

Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2002) - Both worker and female of Mycetomoellerius relictus may be separated at once from the remaining species of the present group by the presence of long propodeal spines, the dorsally armed petiolar node, and the rather scarce hairs. The relatively long lateral pronotal spines (longer than the anterior mesonotal ones) are shared with Mycetomoellerius compactus, which is nevertheless quite distinct by the postero-dorsally excised postpetiolar node and by the presence of one spine at each side of the antero-inferior corner of pronotum. The projecting, hornlike apex of antennal scrobe and the high and conical mesonotal spines distinguish Mycetomoellerius opulentus from M. relictus.

In all examined samples the workers have the second pair of mesonotal projections variable, from blunt teeth to small spines; the slender propodeal spines are thickened in some specimens, and the posterior pair of denticles of the petiole is absent in the Zulia, Venezuela sample.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 11.25° to -16.991667°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Brazil, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname (type locality), Trinidad and Tobago.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

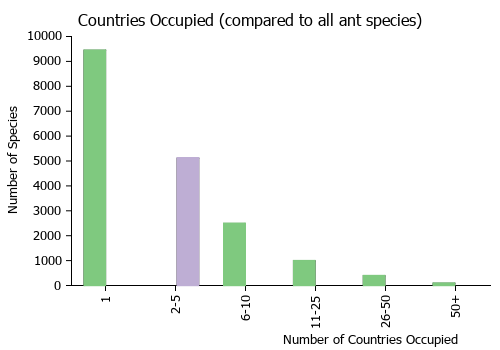

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

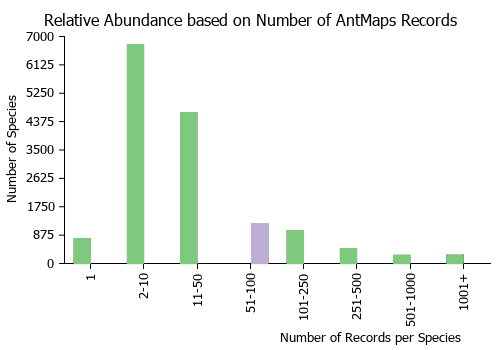

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2002) - This species occurs both in primary forest and in open, cultivated fields, and its nests are often found within the limits of Atta nests. The number of nest chambers is unknown, but at least in one case the upper chamber was at a depth of 20 cm beneath the surface. The nest of a colony discovered by Weber (1968: 143) had as an entrance a bare hole of 10 mm in diameter. Alate forms (sexes not indicated) were present in the latter colony on August 31, 1967. These are timid animals that feign death upon touch.

Castes

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Paratype of Trachymyrmex relictus. Worker. Specimen code casent0901697. Photographer Will Ericson, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by NHMUK, London, UK. |

Queen

| |

| . | |

Male

| |

| . | |

Phylogeny

| Mycetomoellerius |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Based on Micolino et al., 2020 (selected species only).

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- relictus. Trachymyrmex relictus Borgmeier, 1934: 107, figs. 6, 7 (w.q.) SURINAM.

- Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão, 2002: 689 (m.).

- Combination in Mycetomoellerius: Solomon et al., 2019: 948.

- Senior synonym of fitzgeraldi: Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão, 2002: 686.

- fitzgeraldi. Trachymyrmex relictus subsp. fitzgeraldi Weber, 1937: 401 (w.) TRINIDAD.

- Junior synonym of relictus: Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão, 2002: 686.

Type Material

Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2002) - Worker; female; Suriname: Paramaribo; Brazil, Para: Belem. Para types of T. relictus: 3 workers (MNRJ); 3 females, 40 workers (Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo); 1 female, 2 workers (Instituto de Biologia Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro) (examined); syntypes of T. relictus fitzgeraldi: 1 worker (MZSP); 3 workers (National Museum of Natural History) (examined).

According to Borgmeier (1934) the holotype of M. relictus should be deposited at the “Instituto de Biologia Vegetal”; as far as we know this collection should have been first transferred to Sao Bento, Rio de Janeiro, then to Pinheiral, RJ and finally to the CECL. However, we were unable to find it there. Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2002) - TL 3.5-4.7; HL 0.84-1.05; HW 0 .81-1 .03; IFW 0.49-0.60; ScL 0. 76-0.89; TRL1.19-l.54; HfL 1.11-1.35. Light medium brown, head and gaster darker with reddish hues. Integument opaque, indistinctly shagreened. Hairs of variable length, yellowish brown, abundant yet conspicuously scarcer than in Mycetomoellerius opulentus, short and strongly curved on sides of head and alitrunk, on femora and gastric sternum, also on dorsum of head and gastric tergum where they are interspersed among more numerous, longer hairs; hairs on scapes and legs oblique to subdecumbent but not appressed. Dense, very short pubescence of lighter color curved or inclined on head, alitrunk, pedicel and gaster, appressed on scapes and on legs, including the extensor face of the latter.

Head. Mandibles smooth and shining except laterally on base and mesially on proximal half of masticatory margin, where they are finely striate; masticatory margin with one apical and 8 subapical teeth, gradually smaller towards the mandibular base. Frontal lobes semicircular, conspicuously expanded laterad, the interfrontal width well surpassing one half of head width across the eyes. Frontal carinae straight, diverging caudad, fading out at posterior fourth of head. Front vertex and occiput with sparse piligerous tubercles. Preocular carinae very slightly curving mesad above eyes, not intersecting the antennal scrobe, fading out behind eyes at a distance from the posterior orbit which is less than the diameter of the latter. Posterior half of antennal scrobe indistinctly delimited, its apex scarcely projecting in a tuberous fashion, but marked by a small tooth. Supraocular tumulus rather vestigial. Occiput in full-face view nearly rounded laterad, shallowly notched in the middle. Carinae of vertex distinct but blunt, the longitudinal groove between the carinae and the transverse groove in front of them distinct but shallow. Occipital tooth conspicuous, although very small is more developed than in any other species in the group. Inferior occipital corner rounded. Eyes moderately convex, about 10-11 facets in a row across the greatest diameter. Antennal scapes shorter than length of head capsule, little surpassing the occipital corner when lodged in the scrobe. All funicular segments distinctly longer than broad.

Alitrunk. Pronotum with vestigial humeral angles, its antero-inferior corners spinous, the dorsolateral spines high, well-developed. Mesonotum with a pair of very low, multituberculate anterior tumuli followed, in side view, by a similar still lower pair of rather spinous projections; the third pair in the form of very small denticles. Metanotal groove impressed. Basal face of propodeum narrow, laterally partly marginate by an incomplete denticulate ridge. Propodeal spines well developed, slender, oblique, pointed, apically usually a bit deflected downward, but longer than the lateral pronotal spines. Hind femora shorter than length of thorax.

Waist and gaster. Petiole pedunculate, node proper about as broad as long, the dorsal armature of two pairs of denticles always developed , the first pair often vestigial, the second pair always strong. Antero-ventral process of petiole absent. Postpetiole shallowly excavate above postero-mesially, the postero-dorsal border not excised. Tergum I of gaster with minute, evenly distributed but rather indistinct piligerous tubercles; its dorsum antero-laterally marginate.

Queen

Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2002) - TL 5.5-6. 1; HL 1.13-1.24; HW 1.16-1.24; IFW 0.67-0.73; ScL0.95-l.OO; TRL1.73-1.97; HfL 1.46-1 .54. With the same general distinguishing characters as the workers, with the following differences: three ocelli on vertex, the lateral ones smaller. Pronotum with a pair of strong and truncated scapular spines, directed out and forwards, and with a pair of inferior spines pointed down and forwards, smaller than the scapular ones. Mesoscutum surmounted by minute piligerous tubercles, without notable dorsal projections. With the ali trunk in oblique dorsal view, shallow parapses delimited by the parapsidial furrows; mesothoracic paraptera more or less impressed, with a narrow median portion; scutellum ending in two stout and blunt spines, directed backwards, with the sides converging obliquely inwards; meta thoracic paraptera concealed by the scutellum; propodeal spiracle orifices visible. Two strong acute spines on propodeum. Petiolar dorsum with a pair of small teeth. First gastric tergite with a longitudinal ridge on each side; disk with two longitudinal series of small piligerous tubercles, absent in the middle of the segment.

Wings pale brown, completely covered by microtrichia. Fore wing with 5 closed cells (submedian, median, costal, submarginal and marginal); anal vein turned up and fusing with cubito-anal vein, not prolonged beyond the junction. Pterostigma conspicuous, although not pigmented. Hind wing with 5 complete veins, and 2 closed cells; 7 hamuli on anterior margin.

Male

Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2002) - TL 4.0; HL 0.71; HW 0.78; IFW 0.76; ScL 0.76; TRL 1.41; HfL 1.70; FWL 3.8; HWL 2.7 (only one specimen measured). Ferruginous; occipital half of head a bit darker; antennae and legs testaceous. Pilosity as in worker and female, longer inclined or recurved hairs mixed with very fine and short pubescence on body and appendages.

Head. Mandibles finely punctuated on dorsal surface; masticatory margin with only the five basal teeth evident, gradually diminishing toward base (the three additional teeth rudimentary); external margin slightly sinuous. Median border of clypeus moderately convex, with a small anterior notch; dorsal disk of clypeus without notable projections. Frontal lobes rounded and directed forwards, leaving part of the antennal insertions exposed. Frontal carinae divering caudad, not reaching the occiput. Preocular carinae distinct, fading out at the posterior border of eyes. Compound eyes big and convex, filling some 1/2 of the sides of head. Ocelli prominent. Antennae with 13 segments; scape clearly surpassing the occipital corners, nearly three times longer than funicular segments I-III combined; funicular segment I slightly longer than II. Occipital corners rounded, without projections in frontal view. Occipital margin gently concave in the middle between the lateral occelli.

Alitrunk: Pronotum with a scapular spine in form of a short, acute tooth. Scutum narrow and superficially impressed Mayrian furrows; parapsidial furrows and parapsis rudimentary. Mesothoracic paraptera, in dorsal view, slightly narrowed in the middle, where it is impressed and presents a short longitudinal keel, without side projections. Scutellum without dorsal projections, ending as two short, stout and blunt spines, pointing backwards. Metathoracic paraptera concealed by the scutellum in dorsal view. Propodeum with a pair of blunt spines between basal and declive faces.

Waist and gaster: Dorsum of petiole without projections. Postpetiole a little broader than petiole, in dorsal view, superficially impressed above, with the posterior border concave. First gastric tergite without lateral ridges or piligerous tubercles.

Wings as described to the female above, but smaller.

Karyotype

- See additional details at the Ant Chromosome Database.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- n = 10, 2n = 20, karyotype = 20M (Brazil) (Barros et al., 2013; Micolino et al., 2020).

References

- Albuquerque, E., Prado, L., Andrade-Silva, J., Siqueira, E., Sampaio, K., Alves, D., Brandão, C., Andrade, P., Feitosa, R., Koch, E., Delabie, J., Fernandes, I., Baccaro, F., Souza, J., Almeida, R., Silva, R. 2021. Ants of the State of Pará, Brazil: a historical and comprehensive dataset of a key biodiversity hotspot in the Amazon Basin. Zootaxa 5001, 1–83 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5001.1.1).

- Barros, L.A.C., Mariano, C.S.F., Pompolo, S.G.2013. Cytogenetic studies of five taxa of the tribe Attini (Formicidae: Myrmicinae). Caryologia 66, 59–64 (doi:10.1080/00087114.2013.780443).

- Barros, L.A.C., Rabeling, C., Teixeira, G.A., dos Santos Ferreira Mariano, C., Delabie, J. H. C., de Aguiar, H. J. A. C. 2022. Decay of homologous chromosome pairs and discovery of males in the thelytokous fungus-growing ant Mycocepurus smithii. Scientific Reports 12, 4860 (doi:10.1038/s41598-022-08537-x).

- Borgmeier, T. 1934. Contribuiça~o para o conhecimento da fauna mirmecológica dos cafezais de Paramaribo, Guiana Holandesa (Hym. Formicidae). Arch. Inst. Biol. Veg. (Rio J.) 1: 93-111. (page 107, figs. 6, 7 worker, queen described)

- Cardoso, D. C., Cristiano, M. P. 2021. Karyotype diversity, mode, and tempo of the chromosomal evolution of Attina (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini): Is there an upper limit to chromosome number? Insects 1212, 1084 (doi:10.3390/insects12121084).

- Mayhé-Nunes, A. J. and Brandão, C. 2002. Revisionary studies on the attine ant genus Trachymyrmex Forel. Part 1: definition of the genus and the opulentus group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology. 40:667-698. (page 686, Senior synonym of fitzgeraldi)

- Micolino, R., Cristiano, M.P., Cardoso, D.C. 2020. Karyotype and putative chromosomal inversion suggested by integration of cytogenetic and molecular data of the fungus-farming ant Mycetomoellerius iheringi Emery, 1888. Comparative Cytogenetics 14(2): 197–210 (doi:10.3897/CompCytogen.v14i2.49846).

- Solomon, S.E., Rabeling, C., Sosa-Calvo, J., Lopes, C.T., Rodrigues, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci Jr, M., Mueller, U.G., Schultz, T.R. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939-956 (doi:10.1111/syen.12370).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Alonso L. E., J. Persaud, and A. Williams. 2016. Biodiversity assessment survey of the south Rupununi Savannah, Guyana. BAT Survey Report No.1, 306 pages.

- Delabie J. H. C., D. Agosti, and I. C. do Nacimento. 2000. Litter ant communities of the Brazilian Atlantic rain forest region. Pages 1-18 in Sampine Ground-Dwelling Ants: Case Studies from the World's Rain Forests. Curtin University School of Environmental Biology Bulletin 18.

- Delabie J. H. C., R. Céréghino, S. Groc, A. Dejean, M. Gibernau, B. Corbara, and A. Dejean. 2009. Ants as biological indicators of Wayana Amerindian land use in French Guiana. Comptes Rendus Biologies 332(7): 673-684.

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Fichaux M., B. Bechade, J. Donald, A. Weyna, J. H. C. Delabie, J. Murienne, C. Baraloto, and J. Orivel. 2019. Habitats shape taxonomic and functional composition of Neotropical ant assemblages. Oecologia 189(2): 501-513.

- Franco W., N. Ladino, J. H. C. Delabie, A. Dejean, J. Orivel, M. Fichaux, S. Groc, M. Leponce, and R. M. Feitosa. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674(5): 509-543.

- Groc S., J. H. C. Delabie, F. Fernandez, F. Petitclerc, B. Corbara, M. Leponce, R. Cereghino, and A. Dejean. 2017. Litter-dwelling ants as bioindicators to gauge the sustainability of small arboreal monocultures embedded in the Amazonian rainforest. Ecological Indicators 82: 43-49.

- Kempf W. W. 1961. A survey of the ants of the soil fauna in Surinam (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Studia Entomologica 4: 481-524.

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Klingenberg, C. and C.R.F. Brandao. 2005. The type specimens of fungus growing ants, Attini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Myrmicinae) deposited in the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil. Papeis Avulsos de Zoologia 45(4):41-50

- Mayhe-Nunes A. J., and C. R. F. Brandao. 2002. Revisionary studies on the Attine ant genus Trachmyrmex Forel. Part 1: Definition of the Genus and the Opulentus Group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 40(3): 667-698.

- Mayhe-Nunes A. J., and K. Jaffe. 1998. On the biogeography of attini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ecotropicos 11(1): 45-54.

- Pires de Prado L., R. M. Feitosa, S. Pinzon Triana, J. A. Munoz Gutierrez, G. X. Rousseau, R. Alves Silva, G. M. Siqueira, C. L. Caldas dos Santos, F. Veras Silva, T. Sanches Ranzani da Silva, A. Casadei-Ferreira, R. Rosa da Silva, and J. Andrade-Silva. 2019. An overview of the ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the state of Maranhao, Brazil. Pap. Avulsos Zool. 59: e20195938.

- Santos R. J., E. B. Azevedo Koch, C. Machado, P. Leite, T. J. Porto, J. H. C. Delabie. 2017. An assessment of leaf-litter and epigaeic ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) living in different landscapes of the Atlantic Forest Biome in the State of Bahia, Brazil. Journal of Insect Biodiversity 5(19): 1-19.

- Solomon S. E., C. Rabeling, J. Sosa-Calvo, C. Lopes, A. Rodrigues, H. L. Vasconcelos, M. Bacci, U. G. Mueller, and T. R. Schultz. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939–956.

- Vasconcelos, H.L., J.M.S. Vilhena, W.E. Magnusson and A.L.K.M. Albernaz. 2006. Long-term effects of forest fragmentation on Amazonian ant communities. Journal of Biogeography 33:1348-1356

- Weber N. A. 1937. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part l. New forms. Rev. Entomol. (Rio J.) 7: 378-409.

- Weber N. A. 1945. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part VIII. The Trinidad, B. W. I., species. Revista de Entomologia (Rio de Janeiro) 16: 1-88.

- Weber, Neal A. 1968. Tobago Island Fungus-growing Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 79:141-145.

- Weber, Neil A. 1968. Tobago Island Fungus-growing Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 79(6):141-145.